CALIFORNIA

October 28 - November 7

(150 miles)

October 28 - November 7

(150 miles)

I wanted the trip to never end so tacked on the last stretch to Sacramento. So ended the greatest period of my life.

After walking for weeks and months across treeless plains and deserts, I approached the California border.

October 28 First Summit, Sierra Mountains, California:

Seeing my first tree in the Sierras came as a shock. It was a long needled evergreen and there it stood shimmering in the light, a miracle of beauty, a worthy object of worship, a new but familiar old friend.

Passing the second summit I was stopped by a man who was familiar with much of the Donner Route. "You didn't cross the Great Salt Desert in Utah in the exact original route, did you!"

"No," I answered, "I could have, but I stayed closer to interstate 80 for safety."

"Well, of course you didn't," he said, "you couldn't possibly have made it!"

And then for the first time in my life I found myself indignant at this weak assessment of me and my abilities. "Gee whiz, don't challenge me,'' I heard myself saying, ''0f course I could do it!!" And I really meant it. And it's true, I could do it for sure! I basked briefly in the feeling of my hard won confidence. [281]

The false promise of the Hastings cut off had lured the ill fated Donner Party into a trail of doom. But, still somehow they had beaten the Wahsatch, survived the hellish horrors of the Great Salt Desert and by some thread of dogged human endurance flowed around the stubborn wall of the Ruby Mountains. They had sped across the Nevada desert at the truly remarkable rate of 20 miles per day. Considering their starving weakened condition the accomplishment is almost incredible. They pressed across the dreaded 40 Mile Desert and fought their way up the eighty miles of the canyon of the Truckee River succumbing to 50 crossings along its tortured course. Frightened, demoralized and ragged with internal dissention, although refusing to die, the broken and separated remnants of the Donner Party climbed deep into the Sierras. And then with exquisite cruelty, it began to snow. But still for a few days the little people flung themselves repeatedly against the hopeless white barrier at the pass.

Five miles behind the vanguard, the Donner brothers and their families bogged down in 6 inches of falling snow at Alder Creek. George Donner, the kindly captain of the train now bringing up the rear cut his hand trying to repair a broken axle an the midst of the snow emergency. How typical of the Donner bad luck to have an axle break at a time like that!

But the crisis was upon them as they hastily threw up temporary brush huts for the night.

Reports say that by morning the brush tepees sagged under 22 inches of snow, and it continued snowing without stopping for eight days. George was to die slowly there 5 months later of his wound and of heartbreak as the horrors mounted in those snow buried brush tepees. Death and cannibalism would yet pass before his tortured eyes before his rest would come. Tamsen Donner, his devoted wife, would choose to remain behind at his side to the end. She was never seen alive again, her body never found. [282]

Reports say that by morning the brush tepees sagged under 22 inches of snow, and it continued snowing without stopping for eight days. George was to die slowly there 5 months later of his wound and of heartbreak as the horrors mounted in those snow buried brush tepees. Death and cannibalism would yet pass before his tortured eyes before his rest would come. Tamsen Donner, his devoted wife, would choose to remain behind at his side to the end. She was never seen alive again, her body never found. [282]

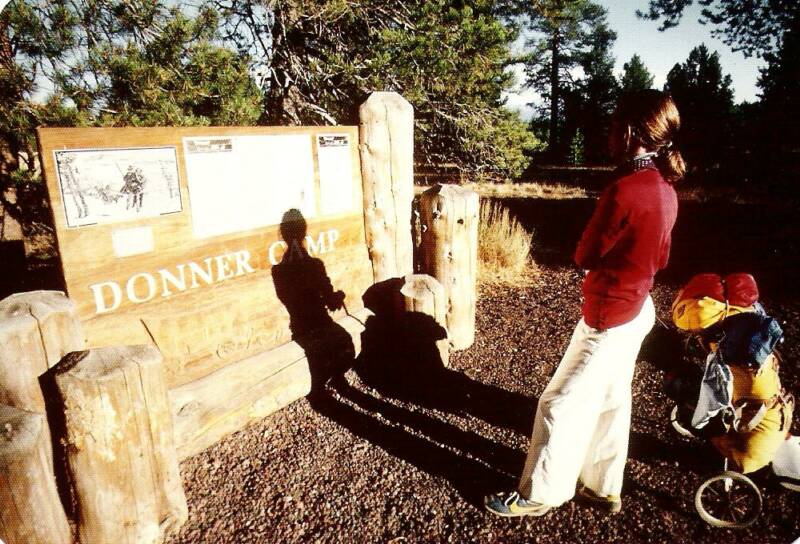

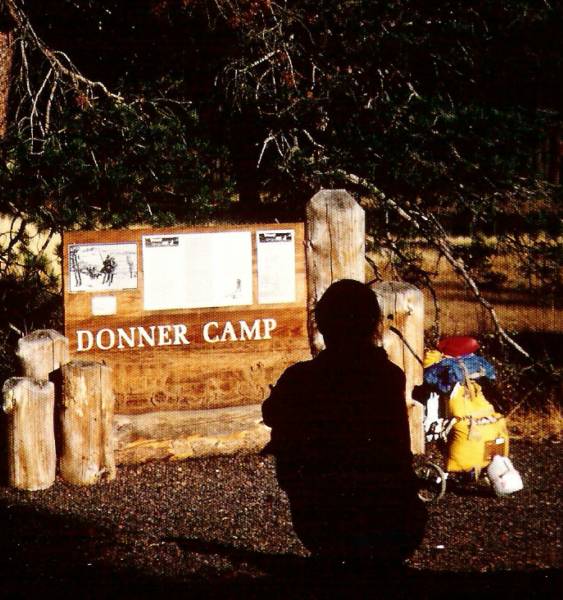

October 29 Donner Camp, Alder Creek, California with Melinda, National Geographic:

We walked on to the Donner Camp. I turned into the parking lot and chuckled to Melinda, ''Melinda, don't ever tell anyone that I went to the outhouse before I looked at the campsites!"

I went to the rest room feeling nothing in particular. After many miles of looking for a bathroom, it did seem strange that I wasn't able to go. I walked back to the parking lot and over to the sign by the Donner Camp with no awareness of emotion....And then suddenly and stunningly there it was! In a low, broad partially treed meadow utterly ordinary yet terribly personal, suddenly, after following the Donner Party six months, 2,000 miles and only occasionally glimpsing them, rarely feeling them, suddenly I'd caught up with them. There they were, stopped forever in this ordinary, yet throbbing place. I approached the sign, pulling my golf cart (which had become my security blanket and my friend) and I read “At this site now so peaceful and easily accessible, one of the cruelest stories in Sierra history was written, the story of the George and Jacob Donner families.”

At the word ''cruelest,'' I was overwhelmed with uncontainable sorrow and grief, just as the term ''suffering humanity" had moved me in South Pass, and I stood helpless as waves of tears gushed from my blinking eyes. Melinda and Micky (People |Magazine) were snapping pictures behind me, not aware of my tears. I felt caught. Finally, alone, unable to read the plaque further, I turned and sought a large boulder nearby to which I fled. I turned to Melinda and said, choked, “I can't read it. I can't get through it." Her face was puzzled and non-comprehending. I glimpsed the kind and sympathetic face of Kathy, and then I sat on the rock curled into a ball, my head buried in my arms on my knees. I had done this to try to regain control, but instead deep sobs racked my body. I could feel my back and rib cage convulsing [283] uncontrollably. I returned to my cart for tissues and tried again to read the plaque only to return to hide on the boulder again.

The Donner Party. To have come so far, so far, so far, as I had just done, and to be stopped forever in this ordinary little meadow....Surely they deserved better than this. Then it all came together, the realization and memory of those spring days along the little Blue River in Kansas, along the Platte, across the Great Plains, through South Pass and the terrible struggle through the Watsatch. We had both known fear in the Great Salt Desert and plodded grimly across the Nevada deserts, burning sun and biting cold, a lifetime, two lifetimes of experiences, many already forgotten. Dear God, to be stopped here in this meadow so close, so close to the goal, stopped dead. They didn't deserve this. A tragedy that knows no adequate words finalized in this ordinary little meadow, right here....

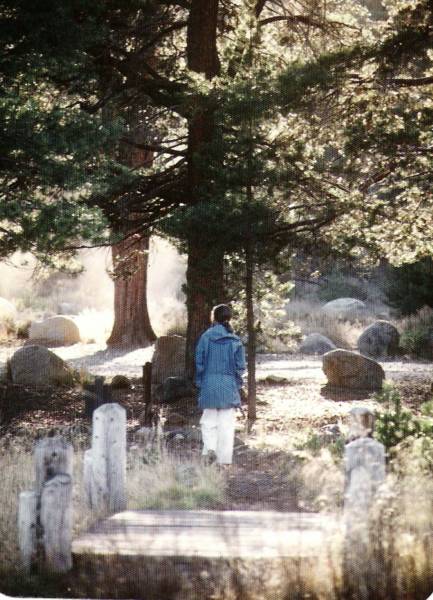

Finally, the part of us that separates us from feelings began to numb me and I began the long process of walling off the feelings that were publicly unacceptable; yet, tragically, I also closed off the brief and priceless oneness I had had momentarily with the Donners. Micky looked confused. I scarcely looked at him. Melinda was armored against softness, a permanent state for her. Kathy was soft and sympathetic but too inhibited to move to me. So I read the plaque with unseeing eyes two times and had no idea what I read. We took the circular path and saw the tepee sites, I in a mushy, unstable state of stiffening up and breaking down. Slowly and lonely I walked alone ahead of everyone, head down and back to the parking lot as David pulled up. He looked at me, and even from a fair distance I sensed that he sensed that I was crying and his face changed from its usual secret melancholia to the deepest compassion and kindness I've ever seen or ever shall and he simply walked up and stood beside me and put his arm around me [284] and stroked my arm. I said "Why am I crying? I've got to stop crying.''

And he said gently. "That's what you came here for."

Such kindness and sensitivity and understanding were more than I could handle so I stiffened and walked to the bathroom to get into my long under- wear. "Maybe that will help," I had murmured.

On emerging I spotted who I assumed was Steve Moore, the park ranger I'd never met but who had encouraged me by letters from the very beginning. I approached him and fighting for control said ''Steve, I'm sorry I'm crying,"

And he with a mask of utter embarrassment said, "Why?"

After that I pulled myself together and conversed with animated brightness brittlely through my tear- swollen face.

My only regret of the trip is that I choked off my hard-won communion with the Donners at Donner Camp. I'm a very well trained woman in that sense anyway. When I am making others uncomfortable (crying) I automatically use all my will to remedy that, in this case at my own expense. Surely after 2,000 miles I had earned the right to cry and to f eel and to commune, yet I failed to assert that earned right. So I stiffened and took charge and walked the path with Steve asking him abut his job and Proposition 13 and how it affected the parts and he rambled on about those irrelevancies and I smiled mightily and brightly through my tear bloated eyes, and the world was back to normal familiar fronts.

Everyone left except Kathy and me. That night in the tent the wind howled in the pines. It would have been an unfamiliar and doubly ominous sound to the plains accustomed Donners. Occasionally I could hear a feeble whack, whack, or clink, click, which sounded for all the world like a weakened person trying to chop down a tree for firewood. Otherwise all human noises were swallowed in the vast silence or occasional crescendo of howling, moan [285] ing wind, Kathy fell asleep and I lay rigidly still on my back. I cried for all of those who died and endured here. The tears spilled at last over the side corners of my eyes, tracing rivulets over my temples, dripping steadily and wetting the hood of my jacket. Occasionally one would follow a path into my ear, feeling suddenly cold. Kathy stirred an hour later and I said, fe?dersky, "This is the spookiest place I ever camped." Spooky was a word choice to make light of what was sheer horror. Whack, whack, whack would go that pitiful ax sound as the cold winds increased their mournful threats.

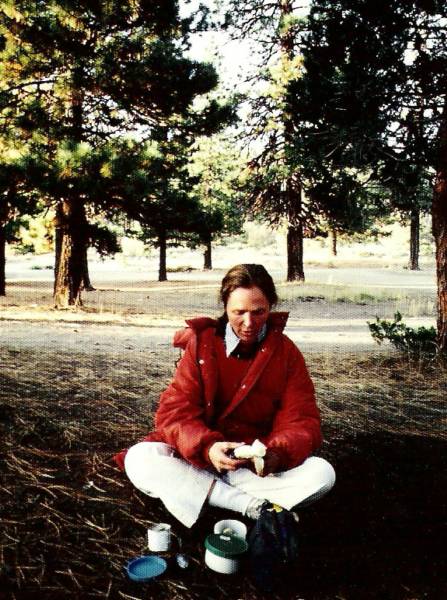

The morning was bitter cold, and then, incredibly, tiny white hard chips of snow were in the air. The chips became flakes and it snowed with varying intensity for 7 (or 2?) days. Kathy and I left Donner Camp and a mile beyond, I became aware of a great flooding sense of lightness as if a great weight I had unknowingly carried had been lifted. I was able to walk Kathy's slow pace without that sense of strain to go faster. Everything looked lovely, even the housing development on the logged mountain.

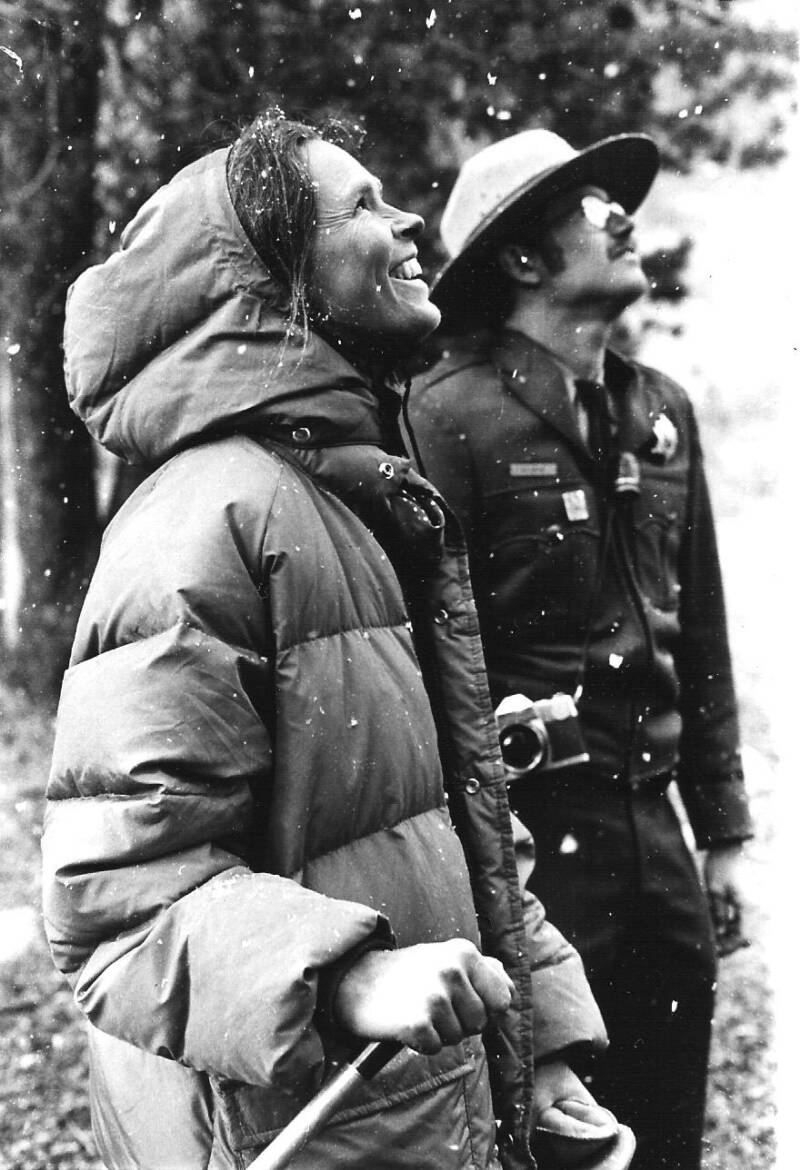

Steve Moore, the Ranger, met us a few miles from Donner Memorial State Park. Our approach to Donner Lake wound through a section of deeply forested emigrant trail. Here the pictures I would have most treasured were never taken. The white snow swirled against the dark evergreens and settled gently over us as confetti at a joyful wedding procession. My arrival at Donner lake, unlike yesterday's soul-wrenching experience (and unacknowledged by press), was light and radiant and underlaid with deep satisfaction and happiness.

I finally found a delightful and growing rapport with Steve. As we stood before the Donner Monument and solemnly read its inscription [286] I turned to Steve questioningly and said, "I don't get it."

After a pause, Steve said, "Neither do I." And we left the woods ringing with deep laughter. In the Donner Museum I stood reverently before a 15 foot high tree stump taken from the Donner Camp and purporting to show the depth of snow when chopped for firewood by a Donner member. My eyes rested on the chopped end. There was a long silence. Steve was standing next to me. "Steve," I said, "that doesn't look like it was chopped with an ax to me." Had I been too disrespectful?

Then Steve answered with a loud laugh of relief. "You're very astute, Barbara. That was obviously cut with a saw. But it still MIGHT have been done by the Donners, who might have had saws."

October 30 Donner Memorial State Park:

October 30 Donner Memorial State Park:

That night Steve and I walked to the edge of Donner Lake and gazed toward Donner Pass at the opposite end. 1n 1978 the edge of the lake is rimmed with twinkling lights of people's homes. A super highway passes through the once virgin woods. Steve said, "It's hard for me to imagine what it was like here in 1846."

But God, I knew. The mountain silhouette then loomed as black and impenetrable as I now imagined. I blocked out the faint roar of traffic and felt the bottomless silence that must have smothered the trapped pioneers who stood here terrified exactly 132 years ago. The wet cold air bit as insistently now as then. The dip in the mountain silhouette, the pass, lured and beckoned now as then, but back then it might as well have been the other side of the moon for many who never lived to approach any closer than this. Steve and I paid them our quiet reverence then and turned and [287] walked back to the car.

I left Donner Lake as quietly as I came. It seemed strange to have no fanfare after reaching such a hard won goal. So I left unannounced, content, satisfied, deeply happy, past the tightly home-packed shores of Donner Lake toward the notch known as Donner Pass.

My struggle up the last big mountain I stood uncomprehending and squinting with disbelief before the approaching dizzy spectacle of Donner Pass, a tousled jumble of house-sized boulders mounting a vaguely tilting sheet cliff. Way back in Ash Hollow, a man who had visited the pass had fairly shouted at me, "How did they do it? with insistent marvel and disbelief. (The Donner Party never did but not for lack of trying.)

Bob Laxalt, the day before had pronounced with scorn and near fear, "They must have been out of their minds to try to scale that sheer cliff with wagons!" They weren't out of their minds, of course, they merely saw no other choice. I had my own toiling to do to surmount the pass so up I went on the old highway, eyes darting unceasingly, searching in vain for any even remotely possible looking wagon route. Visible high to the north was 1-80. I walked on old highway 40. Two ancient road beds were in sight below me to the south, and high, high, dizzily, barely clinging to the vertical granite walls, ran the railroad, built and paid in Chinese blood nearly 100 years ago. Over the pass I labored passing 2,000 year old cypress trees looking virtually identical to me as to frantic pioneer eyes.

I walked for days beyond the pass. The air was fresh, cold and luscious. I followed a lovely river in a kind of Sierra paradise but realized the arduous long descent from the pass was no picnic. The Donner Party would have been a long way from "home free" even if the pass had been scaled. After a series of ups and downs, there began the most astonishing land form of the [288] trip, 50 miles of down hill steep enough to give blisters and sore ankles, steep enough and long enough for me to gasp repeatedly in amazement. I descended through ecological zones, high granite and fir to chaparral and into the darkest and wettest conifer forest imaginable. It was many, many miles before I found a campsite accessible in the steep banks and heavy undergrowth.

Then, some of the most enchanting hours of the trip. Suddenly the air was warm and benevolent, the close rounding hills as intimate as New England's. The soft beige grasses were dotted with spaced parklike scrub oak and occasional broad leafed trees. Gradually the rolling and twisting road wound through small established farms festooned with ancient vines over arbors. The fragrance of ripe and rotting fruit perfumed the balmy air. Small duck ponds backed up lazily behind tiny streams. Even in November neat vegetable gardens sprouted a fresh crop of beets and lettuce. Chickens and ducks and geese scurried, unfenced, while milk cows and horses and lots of goats grazed in languor on the hills. Small orchards nestled in the hollows while tall piny pine stands marched on the hilltops. Clearly this was the paradise image (and reality) that so many pioneers had struggled so long to reach.

I gradually became aware of an uncanny eerie feeling. I felt a strong and special urgent responsibility to take in this Eden Valley completely and totally. It was as if someone else in addition to me was seeing it through my eyes and my senses. Carefully and reverently my eyes caressed every tiny farmhouse, every sparkling duck pond, every nanny goat and grapevine and old barn. I reveled in the paradise murmuring in wonder and understanding, “So this is what they struggled for,” and I felt it a valid struggle. I felt it and breathed it and saw it for those who came so close but died behind the Sierra wall. I walked through it, experiencing it for Tamsen Donner and [289] Eleanor Eddy and old Mrs. Murphy and all those who were left behind. It was a profoundly moving and joyful experience.

The last day of my trip was the 20 mile walk to Sutter's Fort (Sacramento), the goal of the pioneers. For days I had felt schizophrenic, profoundly sad because my trip, almost my life, was nearing an end and deeply happy, triumphant, even jubilant at my accomplishment. So the last day this paradox felt all the more keen. I was alternately elated and mournful, lost and found, ignored and congratulated. A man with his grade school aged daughter stopped. The father had seen my picture in the paper. He announced with an air of historic solemnity to his daughter, "Peggy, I want you to remember this. This woman has walked across the country on the Donner Trail. You can tell your class at school that you met her." Occasionally someone would shout generously, "Congratulations!" or stop to hand me flowers to carry.

Three TV stations did their things off and on during-the day. An incredible incident occurred during one. While the camera and mike were being moved, a car pulled next to me in heavy traffic. A man in his 50's dressed in a garage mechanic's uniform thrust his business card and a $10 dollar bill into my hand saying, "I don't want to take your time but take this and go have dinner and champagne tonight to celebrate. I think it's magnificent what you've done." Miraculously much of this was filmed by the TV camera. I had only minutes before this incident said to the interviewer (in response to the question, "What have you learned on this trip?"), that "I used to see strangers as ominous or threatening or at least indifferent but now to me strangers are simply nice people I don't know yet."

The big bash arrival at Sutters Fort was completely upstaged by a national story that broke in Sacramento one hour and two miles before my arrival. [290] (Computer operated diamond robbery, top story on national news.) Ahhh....such are the fleeting and fickle turns of events that snatch one from the jaws of fame! A special gate was opened for me at Sutter's and a cannon was set off to welcome me; as it would have been staged for the Donner Party, had they arrived in 1846. A Mexican woman had brought her family to see me. “Everyone calls us the weaker sex,” she said with feeling, “but just look what you've showed the world.” (But alas the world wasn't looking!!!) It was a wonderfully confused time with lots of peculiar people jockeying for position to get into the pictures that were flashing. Comic mass confusion reigned for a while and then it suddenly evaporated and it was over, the end. I was happy and hyper and dazed.

November 7 Sacramento:

Alone at night I saw me on TV, and I guess that was the culmination of my personal growth during the trip, the old me and the new me viewing it together. The old me realized I wouldn't have liked the floppy pants, the rolling gait, the too high forehead, etc., etc., but the new and now real true me was stunned with the personal perfection I had created. I loved my gestures, uninhibited, my deep firm voice in response to the interviewer's questions, my earnest and transparent straining to answer truthfully, my expressive face and hands communicating and oblivious to old society notions of pretty femininity. It was a brief and shining moment, so rare! 1 loved the me that I was, unique and perfect.

I slept that night tight along the edge of the fancy king sized bed taking no more room than my sleeping bag would have. In the morning I awoke and realized the walking was over, the tension was over, the journey was over. It was time to get ready for the reporter who would drive me to San Francisco. My golf cart sat faithfully in the corner of the room, the wheels tilting and worn, the rubber tread peeling off. My yellow pack was [291] appropriately dirty with the many stains that had accumulated for two thousand miles. The blotch on the top was from the cheese that melted in Nebraska, the streak on the side from the spilled can of 3-in-one in Nevada. I un-strapped my water jug and then violently backed away. I couldn't bring myself to take my pack off the cart. I paced the room alternately sobbing. "Oh my God," and then laughing, "this is ridiculous." Silly or not dismantling my pack and cart marked a poignant ending I wasn't ready to handle just yet. I thought back to that morning so very long ago (was it just six months?) when frightened and unsure I had been afraid of that same (then clean) yellow pack. Tears of thankfulness and pride blurred my vision. Crying; something I had done daily at first and then hadn't done for months until reaching Donner Camp. Hearing the crunch of a car on the stones outside, I took a deep breath, tenderly removed my pack and went to answer the knock. I was a woman alone on the trail no more. and

I visited an old college friend in San Francisco. A transplanted easterner, she had dabbled in the dizzying variety of mind explorations that sprout endlessly in California. She’s an old hand at telepathy and converses easily about reincarnation as if to were all no more mysterious than my cat's water dish. My trip had ended and I was in that rare state of satisfied completion but bursting aimlessly now with the momentum of recent physical conditioning and purpose. In the aftermath of my trip relaxed and in a happy daze, I simply sat on the couch in the afternoon and passively floated with her relaxed conversation. Suddenly I became aware that Sue's face had changed. It wasn't Sue anymore. It was the face of a plump English looking old fashioned young girl. I blinked startled and there it was the same old Sue talking on without a pause. Within five minutes Sue had changed again, this time to a teen aged boy with red hair and freckles. A quick shake of my head brought back Sue again. There was [292] no mistaking the dissimilarity between Sue's face and the others. There were the obvious physical differences, hair color, skin complexion, age, sex, but the difference that I found most arresting was the facial expression. Sue wears a perpetual guarded tense expression. The faces that had flashed so fleetingly were radiant with humor, beaming with a sense of well being. I waited till the next day to tell Sue about the faces. They had amused me but inexplicably I thought little about them as the conversation had flowed to other topics.

Sue questioned me closely about the faces I had seen. She had a desire that they resemble her mother who had died years before. There had been no resemblance, and the incident was forgotten with typical California acceptance without forced analysis.

In the evening after dinner we relaxed again, Sue sitting across the room and lounging happily. Her face changed, but this time I was alert and interested, not wanting to blink or shake my head to make it disappear. Scarcely moving I said ''Sue it's there.”

"What does it look like?"

"Young girl, late teens maybe, very thin, radiant but beaming through sickness."

“Still there?”

But I shook my head and the vision disappeared. I wasn't frightened, but after all, I am an easterner thoroughly immersed in a culture that scoffs at silly stories of faces or apparitions or whatever. What was I doing sitting there reporting seriously to my friend about how I saw her face change into other people! By the end of the evening, I had seen two more faces, one a woman in her thirties, another a woman in her 50's. Both were the same person as the young girl but older. As I became more confident and less embarrassed the faces stayed longer and I gave long descriptions [293] to an amazed Sue. Finally, not knowing what else to do, I got up and the faces left. I will never forget them, the radiant beaming almost humorous and amused expressions. I had then and have now no explanation for what I saw. I do not believe in ouji boards or anyone else’s psychic stories; I believe only in what I see for myself.

I visited Sue a year later and saw nothing special or unusual. Many months later I mentioned the phenomenon to an acquaintance who said, "I have no explanation for what you saw except that it seems obvious that something was trying to get through an attitude of approval or congratulations to you for the trip." Whether that something was part of myself or a combination, I have no idea, but her explanation is as satisfactory as any.

Donner Lake

Barbara Maat at Alder Creek 10-29-78

Barbara Maat and Steve Moore at Murphy Cabin site 10-30-78

Barbara Maat and Steve Moore on Emigrant Trail west of Alder

Barbara Maat in front of Donner Monument 10-30-78

Barbara Maat and Steve Moore in front of Donner Monument

Barbara Maat at George Donner Tree at Alder Creek 10-29-78

Barbara Maat and Kathy Wolcott (guide) at Alder Creek 10-29

Barbara Maat on Donner Trail west of Alder Creek 10-30-78

Barbara Maat at Weddell signs, Alder Cr 10-29-78

Barbara Maat at Emigrant Trail Museum, 10-30-78

One of the shelters was built against this, the Murphy Rock

in the Sierras, Nat Geographic photos of original trip

original trip, in camp

Slowly and lonely I walked ahead of everyone to the Donner teepee site

To have come so far, so far, so far...

In 1846 the snow depth was up to the statue figure's feet.