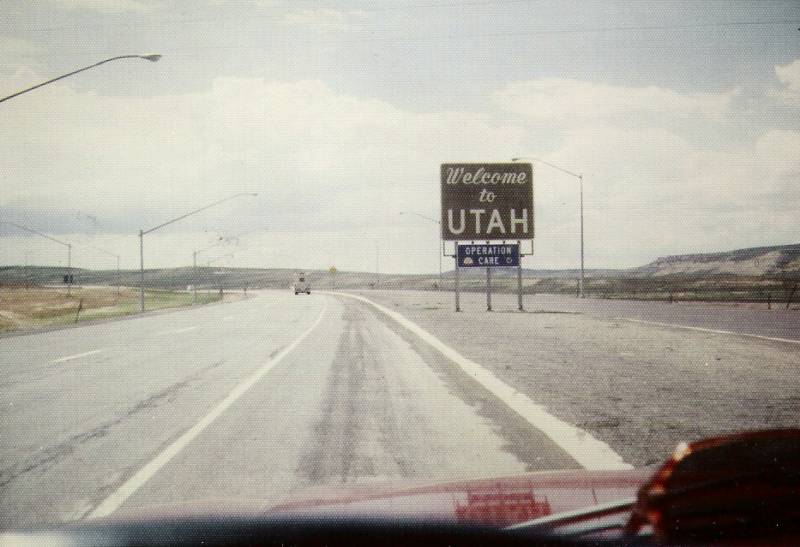

SOUTH PASS AND TO THE UTAH BORDER

July 18 - 28

(120 miles)

July 18 - 28

(120 miles)

Crossing the continental divide was a big moment for the pioneers. This is the full journal entry for my day reaching South Pass. My family was with me.

This morning up early and off to our big day. Very cold. Drove and parked at start and set out, only to run into impassable Willow Creek at once. What an obstacle so soon on our big day! We walked 1/2 mile upstream looking for a spot to ford. Howard heard a rifle and found a beaver dam overgrown with thick growth of willows. We plunged, jumped and dragged through the dew dripping mass and reached a center peninsula, one more stream branch yet to cross! After more exploring (an hour gone already just trying to cross this creek) we found some planks and logs and built a wobbly bridge and finally with some decidedly damp feet, make it across. We retraced our route on the opposite bank and refound the Oregon Trail, conveniently (and essentially) marked with cement posts (a brass Oregon Trail Medallion embedded in each if not already vandalized). The South Pass saddle is 30 miles wide and flat with a gentle steady slope, almost imperceptible in pitch. Our map showed a final crossing to the Sweetwater in 5 miles, a hurdle that gave an edge to anticipation. Again that sense of being more deeply satisfied than ever in my life, the sense of power that miles were churning steadily beneath the effortless rhythm of my own walking. The feeling of being into life, not above it, not beyond it, not escaping from it, but deeply into it. The stillness of the air under the bright cloudless sky [178] had been a nagging concern. When the early morning chill was gone, would we wither in the merciless heat? Then, as is so often the case, my anxiety swiftly increased and changed as the unmistakable deep blue on the horizon signaled stormy weather ahead and heading toward the snowcapped Wind River Mountains to our north. But would we also be caught? Constantly gauging the wind direction, sky, trail, assessing our preparedness (none) and mentally sorting options and contingencies. The clouds edged toward us and the sky darkened to the northwest, darkened?!, BLACKENED!!! So amidst the edge of concern, the edge of appreciation and sensitivity increased, as antelope with their twin babies flew majestically and soared in every direction. The sun still painted the sage, and this against the black sky was simply stunning. Ahead the Sweetwater crossing question was to be faced shortly. The clouds edge slipped under the sun and a sudden windy cold enveloped us. Paula wanted to catch a horny toad at a time like this!!! I almost had a fit. The storm was nearly upon us, and as we approached the alley of the Sweetwater to get low so as to avoid lightning, we all shivered, unprepared for cold rain. Then, as a miracle for sure, the empty buildings of Burnt Ranch! The ranch house was padlocked so we dashed for the barn. It and the house were built a thousand years before (so it seemed) of large squared logs. The only problem was that there was no chinking and 3 and 4 inch spaces were between the logs, walls and ceiling. It was like being in a tinker toy house! But no matter, a seemed like a haven compared to the lashing elements on the open range. We huddled in the ancient horse manure under an old horse blanket as we watched between the logs while the wind bent the willows double along the river bank. The sound of the wind humming and screaming between the logs probably made it sound worse than it was. We sat and pressed the dirty cobwebbed horse blanket against the wall and the wind pressed it against us. The horizontal rain came in gusts but never made much headway. Far from the [179] blazing heat I'd feared, we suddenly found ourselves chattering and shivering and so ate the sugary dried pineapple and chewed beef jerky, "just like the Donners eating hides in the storm," Cliff said. Then, with astonishing suddenness, it stopped. "The eye of the hurricane," I feared, but then some birds started to sing outside and blue sky peeped through the logs. The storm had vanished in an instant.

We stepped out of the barn, unbelieving, into a glorious bright cool day. The storm was past us, the brisk breeze pushing it farther away. First the problem of crossing Willow Creek had been solved and now the storm problem had disappeared. Such ups and downs! The next immediate problem was crossing the swift and turbulent Sweetwater. Perhaps the hundreds of square miles of empty dry sagebrush range had primed me, but the brief green grass of Burnt Ranch next to the Sweetwater seemed like the most perfect heaven.

The tiny tumbled weathered log buildings, picturesque and homey, just proving again that everything is relative, I guess.

The tiny tumbled weathered log buildings, picturesque and homey, just proving again that everything is relative, I guess.

The problem was to re-find the Oregon Trail and to figure a way to cross the river. Despite the fact that I knew it was the wrong direction for the trail, I said with confident authority, "Howard, my instincts tell me to go this way." and I clumped unerringly and blindly toward----a cattle bridge!!!! Another miracle, intuition, instinct or greater self or guide? Whatever, it was a wonderful and irrefutable sense of self discovery. We crossed and climbed up onto the parched plateau and searched and spotted the essential cement marker and were off, happy and exuberant after some more snacks. On and on, mile upon mile, antelope buttes, distant cattle and then my eyes could no longer deny the signs, another storm brewing on the horizon, heading toward the snow caps but clearly we were to be brushed. The fear of lightening on the plat (or flat?) plain is the nerve wracker. The black clouds assembled while our sun shone down on us oblivious to the threat. An hour later and the first clouds dimmed the sun and then the chill wind engulfed us [180] and then tore into us. The black band of clouds moved above us and one by one icy drops of water pelted us like peas from a pea shooter. But the sky was light beyond the wide storm front and before long it passed and we had weathered another problem in triumph! The hot blaze returned. Despite its uniform appearance, the composition of the ground changed occasionally. Crunchy desert rock turned to chalk white powder and then to sharp, cruel, slate-like stones as if recently blasted by dynamite. I caught a note of anxiety for the sore feet of the pioneers' oxen. For a stretch the baked adobe-like clay held glorious translucent gem-type stones. I impulsively gathered a few (the first time in 1,000 miles I succumbed) and unbeknownst to me, Paula did the same when she passed. I've noticed that as we weary, we spread out and struggle, great distances opening between us as we plod on grimly. At a snack and toilet stop, Paula dragged up and showed me her stones. I nearly jumped out of my skin, "Holy Dear God, Paula, that's an Indian scraper!!!" She had unknowingly picked up a perfectly worked Indian scraper! Amazing! I am sure I'll never find an artifact on the trail simply because I BELIEVE I won't. With this frame of mind, I'll probably not even pick one up if I stumble on it, yet I can't seem to shake this mental set.

The miles wore away and Howard left to pick up the car, yet the kids kept on. South Pass was only a couple miles ahead. And then, there it was, designated by two monuments. A more forlorn anti-climax I cannot imagine. Two lonely and touching monuments in the sage, marred suddenly by a railroad track, high tension power lines, cattle fences, yet here we were, incontrovertibly at the continental divide. I felt nothing on the outside, but something deep inside stirred with quiet satisfaction. No one could ever take this from me.

After a treat we started down the Pacific watershed. Immediately the land changed, closer hills and chest-high sagebrush. The trail turned in a [181] curving meander and we silently pushed ourselves the last five miles, exhausted at the end of a brimming full and important day. That night the sixth storm of the day passed overhead.

Today I walked on a plain with the snow mountains to the rear, finally! and desert with mesas ahead and to the south. The traffic was not friendly and I knew there was not a house or ranch or tree for 30 miles. There were more dead and rotting and stinking antelope, badger and jack rabbits on the road than even before. One gas bloated dead jack rabbit lay on the pavement. As I approached it a high speed car ran over it. There was a loud POP and intestines, entrails and all manner of guts exploded and shot in every direction. The stench was horrifying and I was hard pressed not to vomit.

Yesterday while walking an old man stopped to check his car and then I passed him. He was, I think, in a bit of an alcoholic haze, seemed a bit confused. Anyway, after trying to orient himself as to whether or not I was a ghost (in the middle of nowhere) he said, "Hey, isn't that a bit dangerous?" I mean some man could stop and take you in his car by force and ravage your body." His slightly pornographic description has rattled my nerves because he was obviously off on his own sick fantasy. This morning the waitress said, "but aren't you scared!" Honestly, my nerves are suffering. A great weariness has set in. I'm tired of being afraid and especially of handling other people's gloomy assessments. I study the maps and the long stretches ahead look menacing and I wonder where I'll get the will to walk assertively and not defensively.

The passing of the 1,000 mile mark and South Pass I had thought would be a cause for celebration, not the ho hum attitude it seems to bring. [182] It seems that completing 250 miles brought a greater atmosphere of excitement than 1,000 miles from self, family and others. Gloom. Gloom. This too will pass, I'm sure.

On July 20, 1978, I walked into Farson. For two days there Cliff was sick with a fever of 104 deg. On July 20, 1846, exactly 132 years before, a large wagon train of California bound emigrants halted at the Little Sandy River near today's Farson, Wyoming. A fateful decision was in the making. The season was late, although not unreasonably so, and the chance for a 350 to 400 mile short cut loomed ahead. Although the short cut route was an even more unknown quantity to the virgin emigrants than the regular California route, it had the enticing lure of a promise. That promise was that its discoverer, a daring young man named Lansford Hastings, would return personally to lead any wagon train attempting it. The legendary mountain man, Jim Bridger, arrived at the Little Sandy with his partner and conferred favorably with the wagon train. The discussion among the emigrants adjourned with the wagon train splitting, the larger section taking the longer more northerly tried and true route to California. The smaller group, soon to elect a captain named George Donner, took a thoughtful risk and chose the short cut. They did only what any rational humans can do; they soberly gathered together all the facts they could find and on that basis made a decision. No one could ask more than that. Their decision reached so rationally, would seal the deaths of half of them and leave the rest a testimony of unspeakable endurance. The facts they had weighed and relied upon turned out to be false, but at the time there was no way of knowing that. And so the Donner Party took the left fork in the trail, headed for Fort Bridger and then for the short cut beyond. By the time they realized their mistake, it was too late in the season, way too late to turn back, so [183] they did what was really their only option; they pushed on as best they could.

In the motel room were two cheap paint-by-number pictures on the wall of New England church scenes, but I stared and stared at them. The west is grand and vast, majestic and stirring, awesome and harsh, but my God! for beauty tender enough to make your heart ache with longing, there is nowhere on earth that can touch New England. The memory of its scenes in the fall, in the midst of summer, in the deepest winter and in the fragile spring have haunted me for hours.

At the Farson motel a sudden (why is that word so appropriate for so may many phenomena in the west?) wind arose, another ominous storm edge, and howled menacingly without warning. Instantly the world was a beige blur of blazing dust, not unlike the sensation of a snow blizzard. Boxes and miscellany whizzed past the window in streaks. The car outside rocked violently, and then all was quiet. Later a local woman said these tornado type winds are becoming inexplicably more common and more frightening. WOW! I've had enough of this dynamic weather. I recall early in the trip how it thrilled me. Now it's wearing.

On the morning I left Farson, I took a wrong turn, became lost and returned to town to recheck my maps. On setting out again, incredibly I again took the wrong turn and had to double back to start over. My third try at getting off was foiled when I found I'd left behind some equipment, and by then my trudge back to town was frightening as well as frustrating. In my journal I wrote that I was ''at war with myself'' and ''self destructive.'' A year later I realized an uncanny coincidence. That was precisely the spot [184] and date at which the Donner Party agonized so vividly over their route and took their own ultimately self destructive wrong turn. Tamsen Donner is recorded as having been especially ''dispirited'' as the fatal path was chosen.

After a brief rain the sky overwhelmed my self destructive mood with its enchanting clouds, and the air was cold, fresh and invigorating. The clouds determine how majestic and large mountains look and the Rockies (now at my back) looked astoundingly imposing with the clouds even below the peaks in places. I kept gulping the cold fresh air and craning my neck around to see again the mountains. Around me the sage range flattened much like Nebraska, and the desert mesas were mere silhouettes in the distance. The Emigrant Trail cut a deep swale next to me. Once again it became obvious that nothing turns me on like the flat plains, and I can't fathom why.

The trail dropped into a desperately dry baked badlands, eroded into carved beige moonscape. The baked adobe mud made me squint even through my dark glasses. Although it was hot the extreme dryness made it fairly comfortable. After five miles of this we emerged onto the little Colorado Desert, a flat five mile plain leading to the Green River, marked as a distant black fringe of trees, presumably along the river. For a while the white powdered or baked clay was spotted with shint black stones, but this changed to crunchy dry desert gravel in a sage plain, the trail stretching straight and out of sight toward the black tree fringe and distant bluffs.

Despite the fact that I'd read of it in diaries and had a map for contrary proof, I misjudged the distance to the black fringe of trees, estimating a quick and easy two miles. The desert air, occasionally softened by a mysterious sweet aroma, and gravel crunch and dry clear atmosphere and bright hot sun made the first miles thrilling and fun, but the dark fringe of trees appeared no closer after an hour of walking. My crunch crunch crunch walk- [185] ing took on a treadmill aspect as I could discern no landmarks but the seemingly receding black trees. For the first time on the trip I experienced rage of frustration and near despair at my seeming lack of progress. After another half hour the ground suddenly dropped and the river wound bright blue and green grass fringed. The trees never did change much in appearance until the last 100 yards. Whew!

We ascended onto a dry sage area which looked like Nebraska's sand-hills. Paula noticed the prints of unshod horse hoofs and a colt's among them. Cliff and I continued on and over a small hill and came upon a wild horse band. The breeze was not carrying our scent, so they were as startled as we. Their coloring, their wildness, the setting, the lighting, something or everything made them exalting in their sheer beauty. The mares started toward us. Curious? And the stallion, alarmed, also galloped to check us out, and Cliff and I waved frantically for the car. At that point the stallion wheeled and herded his mares away from us. There were 6 lovely, sleek, varicolored mares, one small colt and the stately brown stallion. Their gallop, flowing manes and graceful tails were breathtaking.

The rest of the day was an introduction to parched desert. My arms and face burned. My feet blistered for the first time in months. My eyes hurt despite glasses. We're camped in a dry flat, huddled in the thin shade of the car. My eyes and feet are shot, rendering me quite helpless. We're all quite devastated and awed by the pitiless power of the dry air and the blinding sun. As the evening (8:30) shadows lengthen, the land takes on a softness, but the damage has been done and we can only wait impatiently for the cool and soothing darkness. I'm unnerved by the thought of the deserts ahead. [186]

Today is about the last day of back country trails. It has been priceless, the heart of the trail and the raw land. I'm the better for its indescribable experience.

The Wind River Range is now gone out of sight at our backs. We first sighted them many days ago by Split Rock. To approach, come even and eventually leave such earthmarks gives one a sense of power. Inch by inch even one small person can pass by a great mountain range. Now the snow peaked Uintas lie ahead. And then the Wasatch and then Salt Lake City and then the Great Salt Desert and then....and then...and someday the end.

We camped on the desert, a tiny speck on a planet of baked sand and scratchy plants. I slept under the stars as always. Shortly after we had climbed comfortably into our bags, (incredible to easterners, it cools down the instant the sun sets) I lay peacefully and then stared with interest and amazement as an enormous black insect zoomed overhead sounding exactly like a small airplane. I was more fascinated than alarmed until the damn thing started to hone in on my face. I shrieked and covered my head. Cliff said its passes were 6 inches above my face. The whole family watched and listened to it circle the tents and land on Paula's tent to walk around and explore until darkness engulfed it. We all marveled and agreed it was at least 3 inches long with a 3 inch wing span and sounded like a small airplane.

I slept tensely at first, the bag pulled tightly around my neck.

Today will be a rest day in the terrible heat. Yesterday when we arrived here in Lyman we all gasped and choked and ached as we peaked into the valley. There were the first green irrigated lush grass meadows and trees, leafy trees, [187] for an eternity. Actually, everything is relative. A regular easterner would sniff at it unless desert numbed as we were.

Yesterday passed though a prairie dog town.

Along its western edge the Wyoming terrain gave way to unmistakable mountains and valleys. The tiny towns of Lyman and Ft. Bridger were oases on the edge of the dry range that had been my toil for weeks. In Lyman, we rested at a campground. While taking a side trip to a store our car broke down. Howard went ahead to see about repairs while I waited bored in the car. We were approximately 1/2 mile from the campground. ''Oh phooey,'' I sighed, ''it's too far to walk back. 1'11 just have to wait here." I idly let this musing thought rattle around in my head, and then I sat up with a start. I who had just walked a thousand miles over plains, mountains and deserts was thinking that a paltry 1/2 mile back to the campground was too far!! Quick as a wink I hopped out of the stalled car and scurried back to the camp ground all the while absolutely amazed at how I could have been so dense.

Desert aromas, today a spice rather like poultry seasoning. Some vicious seeds rather like harpoons on tiny coiled rope stick into socks. I stepped barefoot on harsh burrs and spent time pulling them out of my tough soles like porcupine quills.

After Ft. Bridger I stepped onto Interstate 80. The interstate was OK today. I got blown off the road periodically, but it's rather like being buffeted by waves at the ocean, no harm done.

Too many putrid dead animal smells, I'm getting a phobia about it. The odor actually gave me a kind of instant earache. I touched under my ear and [188] the glands hurt, but 50 feet later all was well. It's like the sour pickle test for mumps. I do believe the odor of rotting flesh could eventually drive me crazy if I couldn't get away.

Today was a long windy walk, hot, through and over the mountains called the Bear River Divide, up 4 miles, down 4 miles, up 4 miles, down 4 miles, up 4 miles and down 8.

We reached Evanston and I said, "we're going to EAT for a change!” So we ATE. I had 1 pint yogurt (potato chips and dip), 2 giant hamburgers, 1 quart milk, 1 quart water, strawberries, all in all a heavenly pig out and, honestly, I can't remember when I've been so satisfied.

Lots of woman truckers today. One gave me an especially big smile, a small brief incident but I'll remember it. [189]

Looking back eastward, on the trail

South Pass with the Wind River Range in the distance.

The Wahsatch...wall upon wall of mountains yet to cross

It was beginning, just beginning, to seem possible that I might make it.