CHAPTER 7

NEBRASKA

May 19 – June 1

(172 miles)

NEBRASKA

May 19 – June 1

(172 miles)

Nebraska looked flatter immediately, more open and less settled. Now and then I got a knock out whiff of hog manure. “Why is it that the wind always blows my way just as I pass the hog farms! Whew!”, I grumbled into my journal. I took a primitive farm road and inched my way through two miles of thick marijuana along the ruts. Farmer are supposed to use weed control to eliminate the marijuana. It’s a common joke among the farmers after still another had year for crop prices that “we’d be a heck of a lot richer if we’d herbicide sprayed the corn and harvester the marijuana instead!”

The ironclad old-fashioned rules of morality are alive and well in the rural midplains. The attitude toward marijuana reflected this stability. Nowhere did I ever discern even the faintest curiosity about trying it, in fact, there was a widely propagated and subscribed myth among adults and children alike that “this stuff that grows around here ain’t the smoking kind anyhow.” The hippies occasionally sighted picking it along the roads were dismissed quickly as so many alien vermin best handled with a quick call to the sheriff. The notion that any ordinary human being like you or me would ever smoke the stuff was incomprehensible.

I listened in quite horror one evening to the editor of a small town paper who told approvingly of a local vigilante group who “knew” of a man pushing drugs to young school children. Impatient with the slow “due process of law, the group took the “pusher” for a ride to an empty stretch of road with a ditch and “put a bullet through his head.” I gasped, speechless, dumbfounded. “Sometimes that’s the only way to do it,” he stated with an air of self-satisfied finality.

I reeled in disbelief. The world was suddenly out of whack. This was 1978 not 1900, and this was rural mid-plains farming country, not the deep south, and these farming people were the most loving and generous and cordial I had ever met anywhere. And yet, at that very minute some of my friends back east were probably smoking pot as easily as the farmer lights up a Marlboro cigarette now and then. Then somehow, my innocent friendships in the east made me feel vulnerable. Would I be judged guilty by my associations? I shivered, but the editor and farmer were soon talking of other things, and their faces and manner were as normal as my own father’s. That night the Katydids sang me to sleep and by morning with the world fresh and sunny, the previous night’s conversation seemed a fragment of a disjoined bad dream.

But daily I was falling deeper and deeper in love with the Kansas and Nebraska farm country, the people, the land. Like a Grant Wood painting, life on the farm was straightforward and clear.

But daily I was falling deeper and deeper in love with the Kansas and Nebraska farm country, the people, the land. Like a Grant Wood painting, life on the farm was straightforward and clear.

One day I was in a race with my feet again, no panic, just the familiar daily tension of wondering if I’d find a camping place before they gave out completely. I spotted a farm. No other was in sight for miles. My feet were done. It HAD to be this one. I took a deep breath, tense. Then, thank God, I saw a young woman weeding with a baby carriage nearby. It knew it would be OK, and it was.

With Jan I helped “deliver lunch” to her husband in the fields. It wasn’t my idea of women’s lib, but somehow it seemed right. We bounced along the lane in the pickup truck (what else) until we spotted the tractor far across the field Lloyd was preparing the earth for planting corn as the tractor slowly made its way down the furrows toward us. He joined us and wolfed down his “lunch”. It was 5:30 pm but he would remain in the fields until dark before returning home for his fourth and last meal of the day.

We were sitting next to an abandoned one room school house. Lloyd’s neatly plowed furrows diverged and encircled it. “I went to school there as a kid,” he stated simply. It was fitting and perfect that he was so intimately rooted to this land patch on the face of the earth. Swept away with the romanticism of it all, I asked Lloyd if the planting was the best time of the year for him. “Naw,” he chuckled, “ I think I like the harvest best. When I’m planting, I get pretty tense trying to hold that tractor steady to make the rows perfectly straight.”

“He does have the straightest rows of all the farmers around here,” Jan added proudly.

It was easy to be proud of Lloyd, a big ox of a man, sturdy, simple, honest, and good. He rarely spoke but his silence was the silence of content. He openly adored their new baby, especially thrilled that it was a boy... (no women’s lib there!) His devotion was beautiful, his manner calm and sure.

Lloyd’s worry about straight rows was one I found amusing. What did it matter, I thought, with greater problems like hail storms and droughts and farm prices so much more logical and worthy of worry. But the straight row fetish surfaced again and again crossing the plains. It was right up there comparable to crabgrass and dandelion same in the east. One farmer went so far as to hire another man to plant the rows visible from the road so the neighbors wouldn’t see and laugh at his wavy ones farther in. A farmer outside Ogallala sat gazing out his window from the breakfast table. The corduroy ridges of last year’s wheat crop stretched in a straight ribbed pattern to the horizon. “Thank heaven my brother-in-law planted those rows straight,” he sighed. “Imagine having to look at crooked rows for two whole wheat!” (Wheat is planted every other year with fallow years alternating with the crop years.) A man in Cozad praised a particularly attractive farm on the basis of its crop rows. “Just look at those straight rows!” he beamed. I personally was tuning in the handsome barn and flowerbeds. To each his own! Apparently there was more to this crop row pride than I had first assumed. Farmers preferred flat land partly because they could make the rows straighter. In the endless Nebraska farmlands, a Sunday afternoon ride in the family car became an outing, especially for townspeople, to inspect the local farmers’ rows. One farmer joked about old Jim, who, I was told with a twinkle, “planted his corn in wavy rows to make the rows longer and thereby get a bigger crop!” I laughed heartily but secretly scratched my head for a while trying to figure out why that wouldn’t work.

Not all Nebraska was as predictable as the seasons. One sparkling surprise stands out as a sunflower among daisies. In a typical forgettable cozy village (population 167) I doubled back to a tiny cottage where a woman about my age had given me a nice smile. She met me at the door and without preliminaries invited me to stay overnight. Our rapport was total and instantaneous. We both love butter, were 37, played the flute, read the same books, have 13 year old sons and hate cooking. As we sat munching snacks in her charming cottage, Judy spun a tale of her adventures 14 years before that seemed all the more incongruous in the peaceful conservative Nebraska setting. She had run off with a German poet to Mexico where, totally broke, they visited ancient ruins, lived with peasants, begged rides and food, walked a lot and barely survived. She contracted malaria, tests revealed she had 10 tropical diseases. After having a baby, she divorced her vagabond husband whose violent streaks were becoming too hard to live with. But the revelations of that Nebraska afternoon were not over. Judy confide that she alone in the endless conservative farm country, she, all by herself, is a practicing Hindu! She received instructions from her guru in Hawaii by mail, meditates daily early in the morning. Very early next morning I awoke to the faint exotic aroma of oriental incense. I foolishly found myself strangely unnerved and tried to get back to sleep. It wasn’t exactly that her practices were secret, but somehow, recalling the violent anti-marijuana reactions, I felt it was a private thing, very fragile in Nebraska. How different in Boston where the Hare Krishna people and Black Panthers rub elbows with everyone else on the subways!

Reincarnation is not a scary word to a Hindu, and Judy stated flatly that I was probably a reincarnated member of the Donner Party, one who didn’t make it the first try in 1846. The notion was romantic enough to entice me to spend a few moments wondering just who I might have been in the cast of characters. I was amused to find myself selecting only the noble ones as possibilities! “Let’s see now, was I Margaret or Tanner or...“

My close rapport with Judy faded a bit before we parted. I was sad to feel this happening. For a while I thought I had found a rare soul mate to share mutual understanding (if not religions). But as we talked I found a disturbing and basic difference between us. Perhaps because of Oriental beliefs, perhaps simply because no two people are alike, Judy and I disagreed about women’s paths in life. She felt that there was a natural harmony in male as leader, woman as follower, or a man as dominant, woman as submissive. Harmony or not, I wanted no part of a world or religion with this as an ideal. I left with the image of that sunflower growing and thriving in the patch of pretty daises.

On Judy’s wall hung a framed Hindu saying. As I walked away from her house, I thought of all the small gestures of humanity that people had offered on my Journey, the free cotton candy, the foot massages, the band-aids and fresh cookies, the four leaf clovers and the buckeye, the extra ice in my water jug and warm words of encouragement, the waves and smiles and small gestures of caring that defy description. Even the smallest good wishes took on extraordinary power to fuel me, to anesthetize pain, to buoy my sagging optimism. The Hindu culture knew about such things and expressed the truth:

A kindness done in the hour of need may itself be small, But in worth it exceeds the world.

With Jan I helped “deliver lunch” to her husband in the fields. It wasn’t my idea of women’s lib, but somehow it seemed right. We bounced along the lane in the pickup truck (what else) until we spotted the tractor far across the field Lloyd was preparing the earth for planting corn as the tractor slowly made its way down the furrows toward us. He joined us and wolfed down his “lunch”. It was 5:30 pm but he would remain in the fields until dark before returning home for his fourth and last meal of the day.

We were sitting next to an abandoned one room school house. Lloyd’s neatly plowed furrows diverged and encircled it. “I went to school there as a kid,” he stated simply. It was fitting and perfect that he was so intimately rooted to this land patch on the face of the earth. Swept away with the romanticism of it all, I asked Lloyd if the planting was the best time of the year for him. “Naw,” he chuckled, “ I think I like the harvest best. When I’m planting, I get pretty tense trying to hold that tractor steady to make the rows perfectly straight.”

“He does have the straightest rows of all the farmers around here,” Jan added proudly.

It was easy to be proud of Lloyd, a big ox of a man, sturdy, simple, honest, and good. He rarely spoke but his silence was the silence of content. He openly adored their new baby, especially thrilled that it was a boy... (no women’s lib there!) His devotion was beautiful, his manner calm and sure.

Lloyd’s worry about straight rows was one I found amusing. What did it matter, I thought, with greater problems like hail storms and droughts and farm prices so much more logical and worthy of worry. But the straight row fetish surfaced again and again crossing the plains. It was right up there comparable to crabgrass and dandelion same in the east. One farmer went so far as to hire another man to plant the rows visible from the road so the neighbors wouldn’t see and laugh at his wavy ones farther in. A farmer outside Ogallala sat gazing out his window from the breakfast table. The corduroy ridges of last year’s wheat crop stretched in a straight ribbed pattern to the horizon. “Thank heaven my brother-in-law planted those rows straight,” he sighed. “Imagine having to look at crooked rows for two whole wheat!” (Wheat is planted every other year with fallow years alternating with the crop years.) A man in Cozad praised a particularly attractive farm on the basis of its crop rows. “Just look at those straight rows!” he beamed. I personally was tuning in the handsome barn and flowerbeds. To each his own! Apparently there was more to this crop row pride than I had first assumed. Farmers preferred flat land partly because they could make the rows straighter. In the endless Nebraska farmlands, a Sunday afternoon ride in the family car became an outing, especially for townspeople, to inspect the local farmers’ rows. One farmer joked about old Jim, who, I was told with a twinkle, “planted his corn in wavy rows to make the rows longer and thereby get a bigger crop!” I laughed heartily but secretly scratched my head for a while trying to figure out why that wouldn’t work.

Not all Nebraska was as predictable as the seasons. One sparkling surprise stands out as a sunflower among daisies. In a typical forgettable cozy village (population 167) I doubled back to a tiny cottage where a woman about my age had given me a nice smile. She met me at the door and without preliminaries invited me to stay overnight. Our rapport was total and instantaneous. We both love butter, were 37, played the flute, read the same books, have 13 year old sons and hate cooking. As we sat munching snacks in her charming cottage, Judy spun a tale of her adventures 14 years before that seemed all the more incongruous in the peaceful conservative Nebraska setting. She had run off with a German poet to Mexico where, totally broke, they visited ancient ruins, lived with peasants, begged rides and food, walked a lot and barely survived. She contracted malaria, tests revealed she had 10 tropical diseases. After having a baby, she divorced her vagabond husband whose violent streaks were becoming too hard to live with. But the revelations of that Nebraska afternoon were not over. Judy confide that she alone in the endless conservative farm country, she, all by herself, is a practicing Hindu! She received instructions from her guru in Hawaii by mail, meditates daily early in the morning. Very early next morning I awoke to the faint exotic aroma of oriental incense. I foolishly found myself strangely unnerved and tried to get back to sleep. It wasn’t exactly that her practices were secret, but somehow, recalling the violent anti-marijuana reactions, I felt it was a private thing, very fragile in Nebraska. How different in Boston where the Hare Krishna people and Black Panthers rub elbows with everyone else on the subways!

Reincarnation is not a scary word to a Hindu, and Judy stated flatly that I was probably a reincarnated member of the Donner Party, one who didn’t make it the first try in 1846. The notion was romantic enough to entice me to spend a few moments wondering just who I might have been in the cast of characters. I was amused to find myself selecting only the noble ones as possibilities! “Let’s see now, was I Margaret or Tanner or...“

My close rapport with Judy faded a bit before we parted. I was sad to feel this happening. For a while I thought I had found a rare soul mate to share mutual understanding (if not religions). But as we talked I found a disturbing and basic difference between us. Perhaps because of Oriental beliefs, perhaps simply because no two people are alike, Judy and I disagreed about women’s paths in life. She felt that there was a natural harmony in male as leader, woman as follower, or a man as dominant, woman as submissive. Harmony or not, I wanted no part of a world or religion with this as an ideal. I left with the image of that sunflower growing and thriving in the patch of pretty daises.

On Judy’s wall hung a framed Hindu saying. As I walked away from her house, I thought of all the small gestures of humanity that people had offered on my Journey, the free cotton candy, the foot massages, the band-aids and fresh cookies, the four leaf clovers and the buckeye, the extra ice in my water jug and warm words of encouragement, the waves and smiles and small gestures of caring that defy description. Even the smallest good wishes took on extraordinary power to fuel me, to anesthetize pain, to buoy my sagging optimism. The Hindu culture knew about such things and expressed the truth:

A kindness done in the hour of need may itself be small, But in worth it exceeds the world.

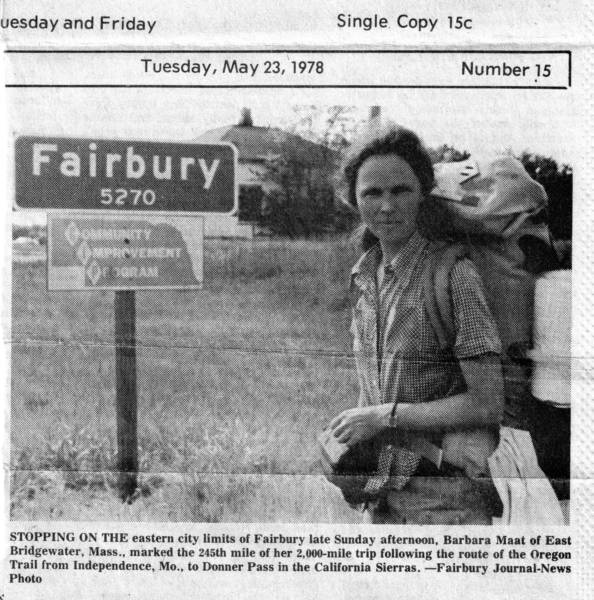

In Fairbury, Nebraska, an encouraging woman named Barbara, called, summoned reporters from three newspapers to interview me. So far the unexpected interest in papers along the way had been fun, but a familiar pattern was emerging that was starting to irritate me. It was the reporters’ version of the common first comments of many.

“But what does your husband think of you doing this?”

“I can’t believe your husband let you do this.”

“Hello,” said the reporter. “Where are you from?”

“Boston area”

“Are you married?”

"Yes.”

“What’s your husband’s name?”

“Howard Maat.”

“What does he do?”

“He’s a college professor.”

“What does he teach?”

“Philosophy and English.”

“Oh,” heavy laden. “what college?”

“North Country Community College.”

“Where’s that? What does he think of all this? Do you have any children? How old? Boy or girl? What are their names?”

Then, after I had been thoroughly defined by my husband and children, the reporter asked, “What is your name?”

It wasn’t that this information was not important because some of it was, or that people weren’t interested in this, because they were. It was just the priority and order of things that annoyed me. Somehow I couldn’t imagine a reverse situation, a reporter interviewing a man hiking the Oregon Trail. “Hello, are you married? What’s your wife’s name? What does she do? Where does she work? What does she teach?” And then, “Oh yes, what’s your name again? Howard?”

A few times I said, “I’d just as soon not talk about my husband because this trip is mine.” This was usually accepted although one reporter in the Nebraska pan handle became belligerent. (Interestingly, he went on to write a very nice article.)

In Fairbury the interview continued. I was learning to hold my breath for the question sure to pop up that I never could answer satisfactorily. “Why are you doing this?” There it was. “Well, I aaaaa, because I want to.” A glance at the reporter told me as usual that this was not enough. “I want to see what it was like for the pioneers.” That sounded silly and juvenile, besides, one reporter pointed out contemptuously, the pioneers didn’t have roads with restaurants along the way. “Well, I aaaaa, uh. I just felt it was something I had to do.” Whoops! There I was painting myself as the compulsive, obsessive neurotic and a weird on at that!

“What made you do this? Are you just trying to prove you can do it?” the reporter helpfully coached.

Truthfully and honestly the answer was no, but my paranoia made me bristle with alarm because to my ears the questioner was saying, “Are you trying to be like a man?” or “Are you trying to overcompensate for deep feelings of inferiority?” And so it went, week after week, fumbling, groping for an answer that would be truthful and “play” well, but it never came. It still hasn’t.

But the Fairbury reporter probed more deeply than many. After initial skepticism, he continued the questioning. Ever the naïve optimist, I said that I saw signs that things were getting better with my feet because I hadn’t cried for four whole days. “But if it’s been that bad,” he said leaning forward earnestly, “why in the world haven’t you given it up and gone back home? No one could say you didn’t give it a good try.”

The questions made perfect logical sense, but from my side it was ludicrous. I felt a great gulf lying exposed between me and him (and probably just about everyone). My difficulties had been severe, mentally and physically. A quick hop on a bus would have ended all the fear and pain honorably. But my problems were of no consequence next to the personal rewards the trip dished up every day. I never even remotely considered giving it up. I would have missed too much. I would have missed a little bird roosting resolutely in her favorite bush two feet from my head for the overrated comfort of my own soft bed at home. I would have sacrificed the electric tingling of trying to outrace a thunderstorm for the bland experience of watching it safely from inside my real estate office. The little scraps of paper with names and addresses lodged in the corners of my pack served as testimony to the new friendships that bloomed daily. To continue was no big deal; anyone would have done the same. The trip fed on itself, but I fear I was not successful in conveying this.

The reporter ended the interview and asked for a picture of me changing my socks. As I stopped to comply, I unceremoniously rolled backward off my feet because of the unbalancing weight of my backpack. There I lay momentarily like a turtle on its back, arms and legs waving feebly in the air. Now THAT would have been a picture for the front page, but the humane man waited tactfully for me to right myself before he clicked.

Right or wrong, fair or not, there’s no doubt that publicity helped my journey by making people more receptive to me. There was nothing like a newspaper story to make me legitimate, to turn people from ordinary skeptical frowners to smiling encouragers. A few days after Fairbury the heat and foot agony had become almost unbearable. I turned into a shaded drive that led to a pleasant farmhouse. Sheltered from the driving ferocity of the blazing sun, I slowed my pace to a snail’s on the approach to the door. After lots of knocking a gracious but startled woman opened her door for me. My story about walking the pioneer trail sounded unlikely and preposterous to her, but she tried to hide her confusion as she escalated her hostess gestures. “Well, come in ... Sit down... Here’s some water... Would you like ice? I’ll put some ice in ... Come out here in the kitchen... Would you like iced tea? Are you hungry? Maybe you’d like a piece of rhubarb pie. Would you like a piece of rhubarb pie?”

Dear God would I ever! But I said discreetly, “I’d love some.” As I was about to leave I glanced down on a chair and saw the Lincoln Star paper. We both saw it at the same time, and on the front page was a picture of me changing my socks. Instantly the good woman’s nervousness vanished and her human curiosity took over. “But, but... well, my goodness, where do you go to the bathroom?” she blurted.

“If it’s number one, I go in the woods,” I explained, “and so far I’ve otherwise waited to get to a proper toilet.”

I bit my tongue as I noticed her startled expression at my overly detailed frank answer. I left relieved that the newspaper article had allayed her nervousness and I was renewed beyond logic by the heavenly rhubarb pie.

That article was the first that preceded me. People who read it watched for me or recognized me as I trudged by. I became concerned that people would feel obligated by the publicity to fuss over me. I began to feel like a pain in the neck when I had to ask for a yard to bed down in. But all in all people were wonderful and some of the ramifications not without humor.

“But what does your husband think of you doing this?”

“I can’t believe your husband let you do this.”

“Hello,” said the reporter. “Where are you from?”

“Boston area”

“Are you married?”

"Yes.”

“What’s your husband’s name?”

“Howard Maat.”

“What does he do?”

“He’s a college professor.”

“What does he teach?”

“Philosophy and English.”

“Oh,” heavy laden. “what college?”

“North Country Community College.”

“Where’s that? What does he think of all this? Do you have any children? How old? Boy or girl? What are their names?”

Then, after I had been thoroughly defined by my husband and children, the reporter asked, “What is your name?”

It wasn’t that this information was not important because some of it was, or that people weren’t interested in this, because they were. It was just the priority and order of things that annoyed me. Somehow I couldn’t imagine a reverse situation, a reporter interviewing a man hiking the Oregon Trail. “Hello, are you married? What’s your wife’s name? What does she do? Where does she work? What does she teach?” And then, “Oh yes, what’s your name again? Howard?”

A few times I said, “I’d just as soon not talk about my husband because this trip is mine.” This was usually accepted although one reporter in the Nebraska pan handle became belligerent. (Interestingly, he went on to write a very nice article.)

In Fairbury the interview continued. I was learning to hold my breath for the question sure to pop up that I never could answer satisfactorily. “Why are you doing this?” There it was. “Well, I aaaaa, because I want to.” A glance at the reporter told me as usual that this was not enough. “I want to see what it was like for the pioneers.” That sounded silly and juvenile, besides, one reporter pointed out contemptuously, the pioneers didn’t have roads with restaurants along the way. “Well, I aaaaa, uh. I just felt it was something I had to do.” Whoops! There I was painting myself as the compulsive, obsessive neurotic and a weird on at that!

“What made you do this? Are you just trying to prove you can do it?” the reporter helpfully coached.

Truthfully and honestly the answer was no, but my paranoia made me bristle with alarm because to my ears the questioner was saying, “Are you trying to be like a man?” or “Are you trying to overcompensate for deep feelings of inferiority?” And so it went, week after week, fumbling, groping for an answer that would be truthful and “play” well, but it never came. It still hasn’t.

But the Fairbury reporter probed more deeply than many. After initial skepticism, he continued the questioning. Ever the naïve optimist, I said that I saw signs that things were getting better with my feet because I hadn’t cried for four whole days. “But if it’s been that bad,” he said leaning forward earnestly, “why in the world haven’t you given it up and gone back home? No one could say you didn’t give it a good try.”

The questions made perfect logical sense, but from my side it was ludicrous. I felt a great gulf lying exposed between me and him (and probably just about everyone). My difficulties had been severe, mentally and physically. A quick hop on a bus would have ended all the fear and pain honorably. But my problems were of no consequence next to the personal rewards the trip dished up every day. I never even remotely considered giving it up. I would have missed too much. I would have missed a little bird roosting resolutely in her favorite bush two feet from my head for the overrated comfort of my own soft bed at home. I would have sacrificed the electric tingling of trying to outrace a thunderstorm for the bland experience of watching it safely from inside my real estate office. The little scraps of paper with names and addresses lodged in the corners of my pack served as testimony to the new friendships that bloomed daily. To continue was no big deal; anyone would have done the same. The trip fed on itself, but I fear I was not successful in conveying this.

The reporter ended the interview and asked for a picture of me changing my socks. As I stopped to comply, I unceremoniously rolled backward off my feet because of the unbalancing weight of my backpack. There I lay momentarily like a turtle on its back, arms and legs waving feebly in the air. Now THAT would have been a picture for the front page, but the humane man waited tactfully for me to right myself before he clicked.

Right or wrong, fair or not, there’s no doubt that publicity helped my journey by making people more receptive to me. There was nothing like a newspaper story to make me legitimate, to turn people from ordinary skeptical frowners to smiling encouragers. A few days after Fairbury the heat and foot agony had become almost unbearable. I turned into a shaded drive that led to a pleasant farmhouse. Sheltered from the driving ferocity of the blazing sun, I slowed my pace to a snail’s on the approach to the door. After lots of knocking a gracious but startled woman opened her door for me. My story about walking the pioneer trail sounded unlikely and preposterous to her, but she tried to hide her confusion as she escalated her hostess gestures. “Well, come in ... Sit down... Here’s some water... Would you like ice? I’ll put some ice in ... Come out here in the kitchen... Would you like iced tea? Are you hungry? Maybe you’d like a piece of rhubarb pie. Would you like a piece of rhubarb pie?”

Dear God would I ever! But I said discreetly, “I’d love some.” As I was about to leave I glanced down on a chair and saw the Lincoln Star paper. We both saw it at the same time, and on the front page was a picture of me changing my socks. Instantly the good woman’s nervousness vanished and her human curiosity took over. “But, but... well, my goodness, where do you go to the bathroom?” she blurted.

“If it’s number one, I go in the woods,” I explained, “and so far I’ve otherwise waited to get to a proper toilet.”

I bit my tongue as I noticed her startled expression at my overly detailed frank answer. I left relieved that the newspaper article had allayed her nervousness and I was renewed beyond logic by the heavenly rhubarb pie.

That article was the first that preceded me. People who read it watched for me or recognized me as I trudged by. I became concerned that people would feel obligated by the publicity to fuss over me. I began to feel like a pain in the neck when I had to ask for a yard to bed down in. But all in all people were wonderful and some of the ramifications not without humor.

I had really begun to drag. No cars passed. The heat had become intense, the worst of the trip. Then suddenly, two more houses and one car gave me iced tea, and I felt like a celebrity again, not bad at all! And then I had a new problem; I could never refuse so kind a offer as someone taking the trouble to bring out a glass with ice and tea so I gulped down all these generous offers and slashed on, my body awash with fluids. Never mind that my legs would twitch all night from the caffeine, what about a toilet, now! I didn’t dare go in the ditch because I felt people in distant farms were (no doubt ha!) watching for or looking for me. (Ah, the woes of celebrity status!)

A few days after the article in the Lincoln Star appeared, I was lying in the grass behind a hedgerow too weary and sore to move despite the gnat and ticks around me. I heard a voice say, “Hello, Barbara” and I jumped. It was the reporter who had interviewed me in Fairbury for the Star.

He had written in the article that I had been in tears daily from my blisters and sore feet. A podiatrist in Lincoln, Nebraska, touched by the story had called the reporter. The podiatrist had said, “This woman needs help. She shouldn’t be having all this trouble. Is there any way you could locate her? I have the day off tomorrow and will gladly go to wherever she is to examine her feet and see what I can do for her. Of course, there would be no charge.” That was the first part of the nice story. The second part was that the reporter had traveled up, down and sideways over the grid-work of farm roads and had by some miracle found me lying out of sight behind the hedgerow.

Later in my journal I wrote, “Unbelievable!! Incredible!! I guess I never will find nicer people than right here in Nebraska!!” But as I sat listening to the story, my emotions were more complicated. I felt silly inconveniencing people about a condition I’d brought upon myself. After the earlier doctor fiasco, I was wary of doctors and preferred to rely on myself thereby feeling less vulnerable emotionally. But the hope for a magic cure from a doctor began to seduce me. I took the podiatrists phone number. Common decency demanded I at least call him. Indeed the reporter had said that if this story had a happy ending, it would make even better reading than his original one. By evening I was feeling less resigned and stoical about my feet and had succumbed to the hope that the podiatrist would be my savior.

Later that night I finally reached the doctor by phone. I could hear my voice quiver. It took only a few seconds to dash my hopes. Apparently the doctor’s initial burst of altruism had faded during the day. The offer to come check my feet was withdrawn under a veil of kind sounding words and voice. Seeking to cover my hurt disappointment I spoke with a clinical voice trying to salvage what I could in the way of information and advice. “Why after 250 miles of walking am I getting new blisters in new places?”

“Because your gait keeps changing as the body adjusts to compensate for the soreness.

“Well what can I do?”

“I can’t really tell much without examining your feet. Is there some way you could get here to Lincoln?”

“No. I have no car.”

“Well, there’s a product out called skin toughener.”

“Nope, I already tried that and it was worthless.”

“It sounds like you need arch supports, but I’d have to fit you for them.”

“What about the kind you buy off the rack in the store?”

“Well, if they don’t fit properly, they do more harm than good, but you could try them. You really should have seen a foot doctor before you started the trip. If your boot doesn’t have a soft sole, you could try a new product called the Spenco innersole.”

The doctor went on to say that if I did see a doctor somewhere eventually I should be sure he was a marathon walking specialist, “Otherwise he’ll be of no use. This is a special field.” He said that he knew one in Hastings if that was on my route. It wasn’t on my route.

The conversation came to an end with me, the goody, goody, gushing thank you’s. I hung up and tried not to cry. The man had been nice enough and concerned but because I had allowed my hopes and emotions to be raised so high, the fall was all the harder. Now all that I had from the good doctor was a new worry that maybe my arches were falling!

The next morning I walked to a new chant, “My arches are falling, my arches are falling, my arches are falling... ” After a few miles a pickup truck pulled along side. A farmer and his Betty Crocker wife extended their arms through the window to shake my hand and say congratulations. Their frank unclouded smiles wiped away my foot preoccupation. They said, “we’d love to have you stay with us,” but I had many miles to go yet before my day was over, so we said goodbye and parted. An hour later the familiar truck appeared again with Mrs. Curray, who rescued me with a pitcher of iced tea and cookies and an invitation to pick me up at the end of the day. We examined the maps and decided on a time and place for the pickup.

During the next few hours the heat became intense. It was blowing in scorching blasts, even smelling like smoke. I kept turning around expecting to see a fire nearby. Something had gone awry within my body. My hands and legs were swelling. I limped on toward the rendezvous point, worried that my eyes had bitten off more than my legs could chew. I didn’t know it then, but including deserts a thousand miles ahead, that Nebraska heat would be the most horrifying I’d experience. Somehow I made it.

Mrs. Curray, solicitous and competent, drove me the miles back to the old homestead, her husband’s boyhood home. Later as I stood barefoot on the cool tile floor of the bathroom, I noticed that something felt peculiar I looked down and saw that my toes were not touching the floor. My feet had swollen so much that it felt like I was standing on fleshy cushions. I crawled to the living room and lay flat on the carpet for a while. I wondered if I was crazy. I said to Mrs. Curray, “Do you think I’m crazy?”

And she answered, “Why no! If you have a dream to follow, then you should follow it.” She seemed like a mother to me as she stood in her cotton print house dress in front of the window. I could see the long straight rows of corn and the barn through the window behind her. A Nebraska woman. I almost cried because she, above all others, seemed to be touched by my physical hardships.

The next day Mrs. Curray dropped me off under threatening skies with a hint of tears in her eyes. The ominous weather was thrilling to me. The sky was and all engulfing movie, changing rapidly, action, contrast, dynamic. There is no way an Easterner can picture it because the sky looks so much bigger here. Part was blue with white clouds and slants of sunshine bouncing off distant silver barns. Part was the deepest darkest storm purple-gray with jagged lightening streaking down. Part was sort of a smoky marbleized cloud business. I’ve never seen such webby, pretty texture in the east. And part was a smoky scary greenish color with shafts of filtered light. Another section was a blurry vertical gray streak, the spot where it was raining. Off to the side was a rainbow. We had driven through a few seconds of torrential downpour and out into sunshine again.

I donned my massive rain regalia, garbage bag over pack, rain pants and parka and walked away; but after only a few drops got me as I walked out from under the dark clouded rain front and into blue sky and sunshine. The whole sky seems higher here as well as wider. A few people stopped. One man and his son returned with a gift. His wife sent fresh breakfast rolls and the clipping from the newspaper. Another son rode out on a horse to meet me. They were handsome people.

My new great hope, the arch supports, aren’t working, pain in arches increasing.

He had written in the article that I had been in tears daily from my blisters and sore feet. A podiatrist in Lincoln, Nebraska, touched by the story had called the reporter. The podiatrist had said, “This woman needs help. She shouldn’t be having all this trouble. Is there any way you could locate her? I have the day off tomorrow and will gladly go to wherever she is to examine her feet and see what I can do for her. Of course, there would be no charge.” That was the first part of the nice story. The second part was that the reporter had traveled up, down and sideways over the grid-work of farm roads and had by some miracle found me lying out of sight behind the hedgerow.

Later in my journal I wrote, “Unbelievable!! Incredible!! I guess I never will find nicer people than right here in Nebraska!!” But as I sat listening to the story, my emotions were more complicated. I felt silly inconveniencing people about a condition I’d brought upon myself. After the earlier doctor fiasco, I was wary of doctors and preferred to rely on myself thereby feeling less vulnerable emotionally. But the hope for a magic cure from a doctor began to seduce me. I took the podiatrists phone number. Common decency demanded I at least call him. Indeed the reporter had said that if this story had a happy ending, it would make even better reading than his original one. By evening I was feeling less resigned and stoical about my feet and had succumbed to the hope that the podiatrist would be my savior.

Later that night I finally reached the doctor by phone. I could hear my voice quiver. It took only a few seconds to dash my hopes. Apparently the doctor’s initial burst of altruism had faded during the day. The offer to come check my feet was withdrawn under a veil of kind sounding words and voice. Seeking to cover my hurt disappointment I spoke with a clinical voice trying to salvage what I could in the way of information and advice. “Why after 250 miles of walking am I getting new blisters in new places?”

“Because your gait keeps changing as the body adjusts to compensate for the soreness.

“Well what can I do?”

“I can’t really tell much without examining your feet. Is there some way you could get here to Lincoln?”

“No. I have no car.”

“Well, there’s a product out called skin toughener.”

“Nope, I already tried that and it was worthless.”

“It sounds like you need arch supports, but I’d have to fit you for them.”

“What about the kind you buy off the rack in the store?”

“Well, if they don’t fit properly, they do more harm than good, but you could try them. You really should have seen a foot doctor before you started the trip. If your boot doesn’t have a soft sole, you could try a new product called the Spenco innersole.”

The doctor went on to say that if I did see a doctor somewhere eventually I should be sure he was a marathon walking specialist, “Otherwise he’ll be of no use. This is a special field.” He said that he knew one in Hastings if that was on my route. It wasn’t on my route.

The conversation came to an end with me, the goody, goody, gushing thank you’s. I hung up and tried not to cry. The man had been nice enough and concerned but because I had allowed my hopes and emotions to be raised so high, the fall was all the harder. Now all that I had from the good doctor was a new worry that maybe my arches were falling!

The next morning I walked to a new chant, “My arches are falling, my arches are falling, my arches are falling... ” After a few miles a pickup truck pulled along side. A farmer and his Betty Crocker wife extended their arms through the window to shake my hand and say congratulations. Their frank unclouded smiles wiped away my foot preoccupation. They said, “we’d love to have you stay with us,” but I had many miles to go yet before my day was over, so we said goodbye and parted. An hour later the familiar truck appeared again with Mrs. Curray, who rescued me with a pitcher of iced tea and cookies and an invitation to pick me up at the end of the day. We examined the maps and decided on a time and place for the pickup.

During the next few hours the heat became intense. It was blowing in scorching blasts, even smelling like smoke. I kept turning around expecting to see a fire nearby. Something had gone awry within my body. My hands and legs were swelling. I limped on toward the rendezvous point, worried that my eyes had bitten off more than my legs could chew. I didn’t know it then, but including deserts a thousand miles ahead, that Nebraska heat would be the most horrifying I’d experience. Somehow I made it.

Mrs. Curray, solicitous and competent, drove me the miles back to the old homestead, her husband’s boyhood home. Later as I stood barefoot on the cool tile floor of the bathroom, I noticed that something felt peculiar I looked down and saw that my toes were not touching the floor. My feet had swollen so much that it felt like I was standing on fleshy cushions. I crawled to the living room and lay flat on the carpet for a while. I wondered if I was crazy. I said to Mrs. Curray, “Do you think I’m crazy?”

And she answered, “Why no! If you have a dream to follow, then you should follow it.” She seemed like a mother to me as she stood in her cotton print house dress in front of the window. I could see the long straight rows of corn and the barn through the window behind her. A Nebraska woman. I almost cried because she, above all others, seemed to be touched by my physical hardships.

The next day Mrs. Curray dropped me off under threatening skies with a hint of tears in her eyes. The ominous weather was thrilling to me. The sky was and all engulfing movie, changing rapidly, action, contrast, dynamic. There is no way an Easterner can picture it because the sky looks so much bigger here. Part was blue with white clouds and slants of sunshine bouncing off distant silver barns. Part was the deepest darkest storm purple-gray with jagged lightening streaking down. Part was sort of a smoky marbleized cloud business. I’ve never seen such webby, pretty texture in the east. And part was a smoky scary greenish color with shafts of filtered light. Another section was a blurry vertical gray streak, the spot where it was raining. Off to the side was a rainbow. We had driven through a few seconds of torrential downpour and out into sunshine again.

I donned my massive rain regalia, garbage bag over pack, rain pants and parka and walked away; but after only a few drops got me as I walked out from under the dark clouded rain front and into blue sky and sunshine. The whole sky seems higher here as well as wider. A few people stopped. One man and his son returned with a gift. His wife sent fresh breakfast rolls and the clipping from the newspaper. Another son rode out on a horse to meet me. They were handsome people.

My new great hope, the arch supports, aren’t working, pain in arches increasing.

For the next few days my journal depicts rapid mental deterioration although I didn’t know it at the time. I was enmeshed in an unfamiliar world of contrasts, overwhelming kindness from outsiders (eliciting an exhausting gratefulness from me) and unremitting physical stress. Any little thing could have pushed me into hysteria and two things finally did. My emotional vulnerability became extreme.

One dynamic semi-retired farm couple took me home and pampered me like the critical case I was. My attraction to them was intense so that every little nuance in their treatment of me assumed extreme significance in my perception of myself. Understandably they were extremely solicitous to the point of actually feeling sorry for me. Margaret shook her hand sadly, “But what are you going to do farther west in Nebraska where there is no shade and it’ll be getting much, much hotter? With the pains you’re having in your feet, they aren’t going to get better. They will only get worse. Oh, I wish there were some way we could gather you in every night and take care of you.”

The sorrier they felt for me, the sorrier I felt for myself until my self-image dissolved into one of a valiant little loser struggling hopelessly. Poor, poor me... what a pathetic girl... I napped in a darkened room. The house was hushed as if for a seriously ill person, which in a way, I was.

In the morning Margaret drove me toward my drop off spot coaxing me persuasively to let her take me an extra 15 miles or so. “No,” I protested feeling a bit unbalanced for my show of stubbornness. But in flat Nebraska all the corn fields looked about the same and before I knew it she had sped two miles past my drop off point. I pulled out my maps. “Whoops! We passed it,” I said apologetically.

She sneaked in a few more hundred yards of road and turned to me saying incredulously, “Do you want me to go back?”

Sweet little me responded meekly, “Oh no, you don’t have to.” We parted, and rose to tears over my perceived inadequacy.

My journal reveals my irrational crack up.

Away I went and about two miles later I suddenly was shocked and horrified and appalled with the full realization that I’d RIDDEN two miles of my route. What a bitter cruel realization! I had struggled 297 miles with blisters and pain and had steadfastly turned down all ride offers, even in my darkest pain, and to have ridden the two miles almost unknowingly in the fresh morning seemed like a cruel happening. I had somehow placed the integrity of the trip at an unbroken line of my footsteps the whole way, and now to have that two mile gap made almost unconsciously and certainly unnecessarily was unbearable. I was sick. I felt worse than I could remember, a horrid futile sinking feeling. I cried for two or three hours, throwing out my whole supply of Kleenex tissue one by one. I never littered before but now I became a veritable Johnny Appleseed strewing the little white tissue papers across the countryside. To go back and retrace was too, much too far.

One dynamic semi-retired farm couple took me home and pampered me like the critical case I was. My attraction to them was intense so that every little nuance in their treatment of me assumed extreme significance in my perception of myself. Understandably they were extremely solicitous to the point of actually feeling sorry for me. Margaret shook her hand sadly, “But what are you going to do farther west in Nebraska where there is no shade and it’ll be getting much, much hotter? With the pains you’re having in your feet, they aren’t going to get better. They will only get worse. Oh, I wish there were some way we could gather you in every night and take care of you.”

The sorrier they felt for me, the sorrier I felt for myself until my self-image dissolved into one of a valiant little loser struggling hopelessly. Poor, poor me... what a pathetic girl... I napped in a darkened room. The house was hushed as if for a seriously ill person, which in a way, I was.

In the morning Margaret drove me toward my drop off spot coaxing me persuasively to let her take me an extra 15 miles or so. “No,” I protested feeling a bit unbalanced for my show of stubbornness. But in flat Nebraska all the corn fields looked about the same and before I knew it she had sped two miles past my drop off point. I pulled out my maps. “Whoops! We passed it,” I said apologetically.

She sneaked in a few more hundred yards of road and turned to me saying incredulously, “Do you want me to go back?”

Sweet little me responded meekly, “Oh no, you don’t have to.” We parted, and rose to tears over my perceived inadequacy.

My journal reveals my irrational crack up.

Away I went and about two miles later I suddenly was shocked and horrified and appalled with the full realization that I’d RIDDEN two miles of my route. What a bitter cruel realization! I had struggled 297 miles with blisters and pain and had steadfastly turned down all ride offers, even in my darkest pain, and to have ridden the two miles almost unknowingly in the fresh morning seemed like a cruel happening. I had somehow placed the integrity of the trip at an unbroken line of my footsteps the whole way, and now to have that two mile gap made almost unconsciously and certainly unnecessarily was unbearable. I was sick. I felt worse than I could remember, a horrid futile sinking feeling. I cried for two or three hours, throwing out my whole supply of Kleenex tissue one by one. I never littered before but now I became a veritable Johnny Appleseed strewing the little white tissue papers across the countryside. To go back and retrace was too, much too far.

Today I reread that section with embarrassment. It is the height of egotism.

The pressures of that day mounted. I misread the map and found no bridge where I expected one. I tried to take a short cut by following a railroad track. It turned into a bridge over the turbulent Little Blue River. There would be no room on the bridge for a train plus me. There were big spaces between the ties. The motion of the current glimpsed through the spaces made me dizzy. My heavy pack and sore feet made me totter unbalanced. I kept glancing back for a train and stopped to listen for a roar. Despite the hot day, I broke into a cold sweat of fear and my breaths came in panicky jerks and gasps. I made it but the tension was all for naught. I later learned that the next train was due in five days!

I was heading for a town where I hoped to find a churchyard to bed down in. My journal describes problems leading to my second breakdown. Y perceptions were distorted, overly personalized and exaggerated.

The pressures of that day mounted. I misread the map and found no bridge where I expected one. I tried to take a short cut by following a railroad track. It turned into a bridge over the turbulent Little Blue River. There would be no room on the bridge for a train plus me. There were big spaces between the ties. The motion of the current glimpsed through the spaces made me dizzy. My heavy pack and sore feet made me totter unbalanced. I kept glancing back for a train and stopped to listen for a roar. Despite the hot day, I broke into a cold sweat of fear and my breaths came in panicky jerks and gasps. I made it but the tension was all for naught. I later learned that the next train was due in five days!

I was heading for a town where I hoped to find a churchyard to bed down in. My journal describes problems leading to my second breakdown. Y perceptions were distorted, overly personalized and exaggerated.

Approaching the town was a sinking disappointment. It was as if a disaster had swept through it. Not a person was in sight. Row after row of tiny, empty or unkempt houses lined the dirt streets. Far away in a trailer, a woman yelled at her kids. It was the most horrible poisonous town I ever saw; not a ghost town (they at least are quaint) but a death-like place, decayed, depressed, really indescribable. I saw a church and a huge brick school. The school on closer inspection proved to be a hollow shell, empty, a rotten tooth. The church was the same way, the steeple half gone.

Across the street a white neatly kept trailer stood in stark contrast to the hovels around. I knocked and a very suspicious, old, proper chunky woman appeared. She opened the door and I started to hold it for her and she yanked it back with fear, revulsion and hostility. I’m sure she thought I was Charles Manson hatchet woman. She said that no one in town would let me unroll my bag on their property. The tears spilled over my face and I began to sob, a terrible error, whereupon she slammed both doors shut and peeked at me from behind the curtains. I walked aimlessly and in a daze of tears, reversing direction every few steps while the woman still peered from behind the curtains. Well, I walked through that godforsaken town crying openly and hopelessly. Once I started crying, I could hardly expect anyone to take me in. I walked through the rotten place and out the other side. I heard someone yelling at me. Police? An old man with a cane was gesturing for me, and I walked back to him. Startled, he said, “Well, what are you crying for?” As I sobbed he led me back to his tiny house to meet his wife.

I hit bottom. They invited me in offering root beer floats, their special rocking chair and foot soaks.

I hit bottom. They invited me in offering root beer floats, their special rocking chair and foot soaks.

I’m resting here for a day after my worst day of the trip, yesterday. I diagnosed my crying last night from exhaustion that I really didn’t even realize I had. Interestingly, after that lady had rejected me, and I cried all through town, I realized that my feet had stopped hurting sometime during the trauma.

The kind white haired man kept saying, ”Why, it’s all right to cry. Even our Lord Jesus wept.” At that point I was even into those convulsive sobbing where you can’t catch your breath, like little kids get. Really alarming.

The kind white haired man kept saying, ”Why, it’s all right to cry. Even our Lord Jesus wept.” At that point I was even into those convulsive sobbing where you can’t catch your breath, like little kids get. Really alarming.

Rose and Everett restored my mind and body with their solicitous ministry. And then, once again, I was on my way.

Through it all, my aesthetic sensitivity was heightened and remained so for days afterward. The next day I wrote:

Through it all, my aesthetic sensitivity was heightened and remained so for days afterward. The next day I wrote:

The wind waves the wheat heads make the fields a soft feathery green instead of the shiny rustling bright ribbons of a few weeks ago. The gray sky or the blue sky, each gives a totally different atmosphere as a backdrop to the farmland scene, both beautiful.

But my stability was still shaky.

Through all these 340 miles, I’ve stumbled upon the kick of living close to the surface, childlike (or babylike). I’ve walked over the crest of a rise and spontaneously said, “Oh boy!” at the view. I find myself grinning and laughing at my thoughts, or suddenly dripping tears at the sight of a dead bunny or bird. When talking to reporters I can barely catch myself from bursting into tears describing the Donner disaster or my hurt at being turned away at farms. I have a prediction: Some day there will be a person in the public eye with enough status and stature to be unrepressed and uninhibited enough to publicly burst into tears and laughter, etc. The thing is, if tears are spontaneous enough, they may last only a few seconds, unlike the common situation where tears mean a bottled up breaking point and are so frightening to all involved. This spontaneity will be a big deal someday, a breakthrough.

As I followed the orange crayon line northwest toward the Platte River on my maps, I became aware of Hastings hovering off my route to the east. The Lincoln podiatrist had mentioned a foot doctor there, I knew I was deluding myself when I felt my feet were getting better. As truly a last ditch effort, I went off the trail and headed toward Hastings. In the back of my mind I was toying with the possibility of having to switch to a bike, or getting a donkey, or something. It would probably be possible to do the trip on sheer grit, but what was the point if I could only half see through the haze of pain. I went to see the doctor.

Strike three for doctors! After a skin softening treatment in a whirlpool, he gave me a lecture on toughening my skin. He showed no interest in my footwear. He pulled out a formidable roll of tape announcing he was going to tape up my arches. I said, “Teach me how to do this in case it works.”

“Oh no, Madam, you could never learn. See a doctor.”

“But if it works and I’m in the middle of Wyoming 50 miles from a town, I’ll have to know how to do it myself.”

“You couldn’t learn how. You’d end up taping your foot in some crazy position.

I should have told him to go to hell, but instead, I laughed sweetly. Meanwhile, I carefully watched what he did. Any dope could have learned it. He did allay one worry. “If you ever get to California, you’ll have the strongest arches in the world.”

I left with the sinking feeling that I’d wasted two days and another $15. I also bought some more worthless junk at the foot section of the drug store.

Within two miles, I had to acknowledge that something felt suspiciously peculiar about my feet. The tape hurt for sure but it seemed more than that. I sat in the front yard of a house in the Hastings suburb and peeled off my shoes and socks. As I bared the skin, a very fine fountain of fluid was actually squirting two inches into the air from a tight blister. The skin had stuck to my sock and peeled off where the doctor had sprayed adhesive to hold the tape. I was faced with a bloody half inch band of blisters and open sores from the edge of the tape across the entire top of my foot from the big toe to pinky and blisters beginning on the knuckles of each toe. In one quick visit the doc had managed to ruin my feet for walking by creating open sores, the one condition I had solemnly guarded against all these hundreds of miles. I cut back the tape with my knife and used up my entire supply of band-aids. The woman working in the yard gave me another whole box of them. I went on with the realization slowly dawning that something had to change drastically.

But there was to be no time for self pity that day. I became oppressed by stultifying heat, humid, hard to breathe. I scooted along as best I could. I was straining and heading for a dot on the map, the farm of a friend of some folk I’d stayed with a week before.

I went on, aiming for Jordans, the name and place suggested. The heat suddenly became awesome. Sweat ran down my face and neck in streams. Three more miles to go and no farm in sight. I became nervous that Jordans would be on another road. Then I saw a farm and hoped nervously that the mailbox would say Jordan. Two more miles to go. Sky began to blacken ahead; tornado? The mailbox DID say Jordan! I straightened my shirt, removed my glasses and hat and knocked. After a long while an old lady appeared, scowling. Her disapproving looks and manner made my heart sink, but I played my smiling friendly role, and her husband came up and was nice, but she made it clear that she wanted no part of me. So I waved and turned and dissolved in sobs and limped away into a gathering storm.

Strike three for doctors! After a skin softening treatment in a whirlpool, he gave me a lecture on toughening my skin. He showed no interest in my footwear. He pulled out a formidable roll of tape announcing he was going to tape up my arches. I said, “Teach me how to do this in case it works.”

“Oh no, Madam, you could never learn. See a doctor.”

“But if it works and I’m in the middle of Wyoming 50 miles from a town, I’ll have to know how to do it myself.”

“You couldn’t learn how. You’d end up taping your foot in some crazy position.

I should have told him to go to hell, but instead, I laughed sweetly. Meanwhile, I carefully watched what he did. Any dope could have learned it. He did allay one worry. “If you ever get to California, you’ll have the strongest arches in the world.”

I left with the sinking feeling that I’d wasted two days and another $15. I also bought some more worthless junk at the foot section of the drug store.

Within two miles, I had to acknowledge that something felt suspiciously peculiar about my feet. The tape hurt for sure but it seemed more than that. I sat in the front yard of a house in the Hastings suburb and peeled off my shoes and socks. As I bared the skin, a very fine fountain of fluid was actually squirting two inches into the air from a tight blister. The skin had stuck to my sock and peeled off where the doctor had sprayed adhesive to hold the tape. I was faced with a bloody half inch band of blisters and open sores from the edge of the tape across the entire top of my foot from the big toe to pinky and blisters beginning on the knuckles of each toe. In one quick visit the doc had managed to ruin my feet for walking by creating open sores, the one condition I had solemnly guarded against all these hundreds of miles. I cut back the tape with my knife and used up my entire supply of band-aids. The woman working in the yard gave me another whole box of them. I went on with the realization slowly dawning that something had to change drastically.

But there was to be no time for self pity that day. I became oppressed by stultifying heat, humid, hard to breathe. I scooted along as best I could. I was straining and heading for a dot on the map, the farm of a friend of some folk I’d stayed with a week before.

I went on, aiming for Jordans, the name and place suggested. The heat suddenly became awesome. Sweat ran down my face and neck in streams. Three more miles to go and no farm in sight. I became nervous that Jordans would be on another road. Then I saw a farm and hoped nervously that the mailbox would say Jordan. Two more miles to go. Sky began to blacken ahead; tornado? The mailbox DID say Jordan! I straightened my shirt, removed my glasses and hat and knocked. After a long while an old lady appeared, scowling. Her disapproving looks and manner made my heart sink, but I played my smiling friendly role, and her husband came up and was nice, but she made it clear that she wanted no part of me. So I waved and turned and dissolved in sobs and limped away into a gathering storm.

Then began a startling exploration into myself. Her attitude of suspicion, fear and revulsion had infuriated a deep part of me previously untouched. Behind my tears a new sensation stirred, at first vaguely but then powerfully. I felt a strong urge toward violence and would have taken great pleasure in living up to her fearful image of me by swearing obscenities at her, pushing her so she would stumble and fall and just generally scaring the life out of her. The image of violence became actually sensuous. Her attitude and expectations had stimulated this in me, ordinarily so meek and civilized. Later I wondered if her fear posture was similar to the goads that set off criminals’ acts of violence against their victims. In retrospect, I consider the episode one of the trip’s most revealing incidents.

The atmosphere that had been so oppressive had been the weather low pressure front preceding a storm. With shocking rapidity the wind picked up. The thunder heads blackened the sky and I had suddenly a minor emergency on my hands, evening, gathering bad storm, no plans. I spied a mailbox one mile ahead as lightening flashed. I was the tallest thing on a flat field but I just walked faster and faster until I was running, trying not to bounce the pack, ignoring my screaming feet. I felt something hit me and noticed a fragment of ice, then another ahead, hail! The pieces were not round but jagged, ½ inch wide. Finally, I reached the house and rang the bell. In the distance, four miles, I could hear sirens and bells; tornado warnings in Kenesaw? No one answered at the house. Were they all in the storm cellar?

While leaning under the eve, I put on all my rain stuff and pack cover. At that moment I suddenly had a great surge of confidence. I was taking charge of events instead of being battered by them. I decided to walk on toward Kensaw to find a church. Hail and rain splattered and stopped as the storm passed to the north. Finally I spotted a pleasant brick house and limped up the drive.

An old smiling man (thank God) came out. Later he confessed that he’d thought I was an old crippled bum, “bent over, limping and moving so slowly with such small steps.”

Mrs. Miller emerged and gasped when she tried to hoist my pack. She said with complete seriousness, “Why, you need a little red wagon to pull!” The image that flashed in my mind is unforgettable, and dear.

While leaning under the eve, I put on all my rain stuff and pack cover. At that moment I suddenly had a great surge of confidence. I was taking charge of events instead of being battered by them. I decided to walk on toward Kensaw to find a church. Hail and rain splattered and stopped as the storm passed to the north. Finally I spotted a pleasant brick house and limped up the drive.

An old smiling man (thank God) came out. Later he confessed that he’d thought I was an old crippled bum, “bent over, limping and moving so slowly with such small steps.”

Mrs. Miller emerged and gasped when she tried to hoist my pack. She said with complete seriousness, “Why, you need a little red wagon to pull!” The image that flashed in my mind is unforgettable, and dear.

I stayed with the Millers a few days until the oozing sores scabbed over enough to continue. Although I wasn’t aware of it at the time, this was the turning point of the trip, for here I took the weight of my pack off my back and feet once and for all and put it on wheels, a golf cart.

I liked the Miller’s attitude. Mr. Miller, a practical man, didn’t sit around bemoaning my sorry condition; he set about wracking his brain for solutions. Mrs. Miller had started the process when she instinctively blurted the little red wagon idea. We finally settled on the golf cart.

I liked the Miller’s attitude. Mr. Miller, a practical man, didn’t sit around bemoaning my sorry condition; he set about wracking his brain for solutions. Mrs. Miller had started the process when she instinctively blurted the little red wagon idea. We finally settled on the golf cart.

The Patt’s, the Miller’s daughter and son-in-law, gave me their golf cart. Mr. Miller welded a brace to it and we tied on my pack. It seemed like such an ignominious comedown to see my beloved pack tied to a golf cart! I actually had come to like the feel of my pack on my back, only my feet objected.

The golf cart became a new adjustment; my self image was suddenly radically altered, no more chance for the elite backpacker image. Now I would be a strange old woman pulling a cart, an oddity.

Thursday morning, Hannah Miller packed six sandwiches, three fried egg and three peanut butter and jelly. I ate them all a mile beyond her house! Hope and optimism and new beginnings were my feelings as I left. I walked for and hour on back roads with the wind rustling the maturing wheat around me.

The golf cart became a new adjustment; my self image was suddenly radically altered, no more chance for the elite backpacker image. Now I would be a strange old woman pulling a cart, an oddity.

Thursday morning, Hannah Miller packed six sandwiches, three fried egg and three peanut butter and jelly. I ate them all a mile beyond her house! Hope and optimism and new beginnings were my feelings as I left. I walked for and hour on back roads with the wind rustling the maturing wheat around me.

Three times I passed on oldish man running a road grater. He was vaguely Mexican with dark skin. His teeth were rotten or missing, his eyes slightly crossed. Oily hair hung limply over his ears. He was dirty, disreputable looking. Early in the day I had firmly answered his questioning look by calling out, “I’m walking the Oregon Trail.”

Toward the end of the day he stopped far ahead, parked his road grater across the road and waited for me. In flat treeless Nebraska, there was no place to run, no place to hide. He crept behind his machine and watched as I approached. I took a deep breath, tried to maintain an attitude of calm and walked to ward the machine, careful not to slow my pace. He edged hesitantly toward me, his hand nervously reaching in his pocket. “Hello,” I said.

He pulled his hand out of his pocket. In his palm was a little scrap of paper and the stub of a pencil. “Would you write your name down here for me?” he pleaded gently. “You sure are one magnificent woman. It is an honor meeting you.” Then he confided shyly, “I like history too.”

It was a wonderful walk. I could look around (no backpack to hinder me) and savor the scene. I got my first glimpse of Nebraska’s famous sand hills, round undulating hills of sand, dry, covered with sparse grass for grazing.

With my golf cart I walked 23 miles, way too far for my still tender wounds, but it gave me a big confidence boost. I reoriented myself to my pilgrimage, stopping reverently beside the lone pioneer grave of Susan Hall who died on the trail at age 34.

Her story brings a pang of emotion to the otherwise impersonal landscape. It is said that her husband, grief stricken at her death camp, was unable to tear himself away to continue westward with his wagon train. Instead, he placed a temporary marker on her burial site and returned alone on foot to St. Joseph Missouri to procure a proper grave stone. He then retraced his route, carrying the little monument in a wheelbarrow, back to the prairie. Out of the thousands who died on the trail, Susan Hall is one of only a rare few whose name and burial place is known today.

I renewed pioneer identification as the sight of the Platte River in the distance brought a surge of anticipation and a big grin. I reached historic Fort Kearney and my spirits soared. Incredibly, I fell asleep on the lookout next to the ancient parade grounds. Reaching the Platte was the completion of my first big goal, and I snoozed in the sun in the delicious rest of satisfied exhaustion.

The Platte River is important and special. One can sense that with a quick glance at any Nebraska map. Its lazy colossal meander undulates in easy disregard and defiance of the rigid right angles of section lines and highways. Historically it was the dominant great road for east-west travel migrations for thousands of years. Ancient Indians were following its course for centuries before white people dreamed of the new world. Later explorers and fur trappers and mountain men traced its path across the plains. For the pioneers traveling with their herds of thirsty stock, the rivers became their lifelines as they inched their way across the vast featureless plains. The Platte was the Granddaddy of them all. In the old days the weary emigrants followed it hundreds of miles without seeing even a single tree to break the horizon line. Pioneer diaries chortle and chuckle in the astonishment at its peculiar characteristics. “Too thick to drink and too thin to plow” was the familiar muddy refrain. “A mile wide and an inch deep”, “a river without banks to hold it in”, a joke that turned exasperating when it softened the lowlands making the oxen strain through the mud.

Today’s interstate 80 follows its shores as surely as yesterday’s wagon train, but the resemblance stops. The mighty river has been tamed beyond recognition. Dams and irrigation diversions have reduced the “mile wide” to a veritable trickle and extracted its silt to a crystal clear sparkle. Its once treeless banks smoothed by prairie fires or buffalo grazing are now a veritable tangle of cottonwoods and jungle growth. The old oceans of grass have disappeared along with the brown carpets of buffalo as surely today’s skyline is broken with pivot irrigators, silver silos, fields of corn and wheat and verdant clumps of trees cuddling peaceful farmhouses.

Everything has changed since 1846, everything that is except the weariness and the thrill of reaching, finally, and important landmark.

Toward the end of the day he stopped far ahead, parked his road grater across the road and waited for me. In flat treeless Nebraska, there was no place to run, no place to hide. He crept behind his machine and watched as I approached. I took a deep breath, tried to maintain an attitude of calm and walked to ward the machine, careful not to slow my pace. He edged hesitantly toward me, his hand nervously reaching in his pocket. “Hello,” I said.

He pulled his hand out of his pocket. In his palm was a little scrap of paper and the stub of a pencil. “Would you write your name down here for me?” he pleaded gently. “You sure are one magnificent woman. It is an honor meeting you.” Then he confided shyly, “I like history too.”

It was a wonderful walk. I could look around (no backpack to hinder me) and savor the scene. I got my first glimpse of Nebraska’s famous sand hills, round undulating hills of sand, dry, covered with sparse grass for grazing.

With my golf cart I walked 23 miles, way too far for my still tender wounds, but it gave me a big confidence boost. I reoriented myself to my pilgrimage, stopping reverently beside the lone pioneer grave of Susan Hall who died on the trail at age 34.

Her story brings a pang of emotion to the otherwise impersonal landscape. It is said that her husband, grief stricken at her death camp, was unable to tear himself away to continue westward with his wagon train. Instead, he placed a temporary marker on her burial site and returned alone on foot to St. Joseph Missouri to procure a proper grave stone. He then retraced his route, carrying the little monument in a wheelbarrow, back to the prairie. Out of the thousands who died on the trail, Susan Hall is one of only a rare few whose name and burial place is known today.

I renewed pioneer identification as the sight of the Platte River in the distance brought a surge of anticipation and a big grin. I reached historic Fort Kearney and my spirits soared. Incredibly, I fell asleep on the lookout next to the ancient parade grounds. Reaching the Platte was the completion of my first big goal, and I snoozed in the sun in the delicious rest of satisfied exhaustion.

The Platte River is important and special. One can sense that with a quick glance at any Nebraska map. Its lazy colossal meander undulates in easy disregard and defiance of the rigid right angles of section lines and highways. Historically it was the dominant great road for east-west travel migrations for thousands of years. Ancient Indians were following its course for centuries before white people dreamed of the new world. Later explorers and fur trappers and mountain men traced its path across the plains. For the pioneers traveling with their herds of thirsty stock, the rivers became their lifelines as they inched their way across the vast featureless plains. The Platte was the Granddaddy of them all. In the old days the weary emigrants followed it hundreds of miles without seeing even a single tree to break the horizon line. Pioneer diaries chortle and chuckle in the astonishment at its peculiar characteristics. “Too thick to drink and too thin to plow” was the familiar muddy refrain. “A mile wide and an inch deep”, “a river without banks to hold it in”, a joke that turned exasperating when it softened the lowlands making the oxen strain through the mud.

Today’s interstate 80 follows its shores as surely as yesterday’s wagon train, but the resemblance stops. The mighty river has been tamed beyond recognition. Dams and irrigation diversions have reduced the “mile wide” to a veritable trickle and extracted its silt to a crystal clear sparkle. Its once treeless banks smoothed by prairie fires or buffalo grazing are now a veritable tangle of cottonwoods and jungle growth. The old oceans of grass have disappeared along with the brown carpets of buffalo as surely today’s skyline is broken with pivot irrigators, silver silos, fields of corn and wheat and verdant clumps of trees cuddling peaceful farmhouses.

Everything has changed since 1846, everything that is except the weariness and the thrill of reaching, finally, and important landmark.

Friday evening Ft. Kearny

I have a feeling that this marks the end of one phase of the trip, a completion. The end has come abruptly, but things will never be the same.

Whatever happens in the future, I’m no longer committed totally to backpacking. The golf cart may wear out, but wheels are now part of my image, quite an adjustment for my ego! (Later on, I would come to feel proud of it.)

Reaching the Platte is a milestone. Now after 380 miles, I feel legitimate. Now, following the Platte, I hardly need a map. I feel I’ve been tested and passed, barely!

My relatively populated, civilized farming area is nearing an end and will never reappear to this extent throughout the journey.

Until now the great physical rigors have been internal, my own foot problems, etc. So far the weather has given me a break. In the future I expect more external rigors, heat, terrain, water scarcity, lack of shade, and God only knows what else!

I have a feeling that this marks the end of one phase of the trip, a completion. The end has come abruptly, but things will never be the same.

Whatever happens in the future, I’m no longer committed totally to backpacking. The golf cart may wear out, but wheels are now part of my image, quite an adjustment for my ego! (Later on, I would come to feel proud of it.)