UTAH

July 29 - August 16

(80 miles)

July 29 - August 16

(80 miles)

The sign said welcome to Utah. I allowed myself a deep daring breath and unabashed smile and then the thought ever so fleeting, “I think, I'm pretty sure, I mean, I think I might actually make it!” It was beginning, just beginning, to seem, possible.

Feeling a little bit like ''The Little Engine That Could" in the child's story, I walked on westward.

Soon after entering Utah, I-80 and I began the gradual descent into Echo Canyon. The landscape grew more dramatic as the canyon walls steepened and reddened. For the Donner Party the descent was a funnel leading unknowingly into a trap. Ahead was the blind wall of the Wahsatch Mountains. Crossing those mountains would exact a three week toll in time and backbreaking effort before they would be left behind. But for me Echo Canyon was an exciting land form change, an accelerated experience in beauty.

Today fragrance of anis or licorice is in the air.

Camped high on the side of Echo Canyon. Listened to the hum of traffic all night. Tried to imagine sounds when pioneers streamed through, then realized that today's traffic hum will also some day be extinct, so I tried to absorb today's historic period movement too. Watched also today's historic trains far below. One had 110 cars, all kinds. Very peaceful to [190] be so high above the activity and to have such a panoramic view. At night I watched the stars, shooting stars, and satellites, later a halfish moon.

Next morning walked up Echo Canyon, step by step becoming more dramatic. Everyone and everything throughout history streamed through here, old roads and trails next to the railroad and the dominant Interstate 80. At one time in the morning there was a plane, train, trucks, cars, motorcycles (no bikes), and me walking. The north canyon wall steepened into dazzling orange cliffs and caves and holes and fissures and grottoes. As the sun heated, the colors became more vivid until I realized I was seeing my first really verdant greens in 3 months. The startling side canyons, winding back and up to secret Indian places, captured enough water to flourish cool grove of trees and wild green grassy meadows, while high above the orange walls faded again into the familiar harsh sage and desert sand. Frosty clouds swarmed in the deepest blue sky which pulsated behind the orange cliffs. I could nearly drink-in the verdant almost forgotten green. How many months the blue sage range and tan grass plains had been my reality!

Cliff said, "Mom, in the book Sing Down the Moon, in the end when they got married, this is exactly, EXACTLY the kind of place I imagined!" We peered up the perfect heaven of another side canyon and I gave silent tribute to the beauty which equaled New England idyl. Howard jogged up the canyon, "It's the greatest road you'll ever walk."

Then a few miles up the old road I looked up for the millionth time and spotted some old graffiti, the careful and fancy calligraphy of the old days, dated 1885, with 2 names plus the word "artist" after each and an old carefully lettered advertisement, Salt Lake House, Salt Lake City. The perfect touch to tie in the human history of the canyon.

Through all this my feet were protesting the feat more and more [191] insistently until they felt like mush spiked now and then with shooting pains. Am also finding tiny water blisters on arms and legs more and more.

Next morning the sun and clouds had changed and yesterday's fiery cliffs had become a wintry brown, the atmosphere now cold and unfriendly.

Like the stem and cross bar of a T the west end of Echo Canyon leads smack into the Wahsatch Mountains, a virtual blank wall. The Donner Party turned north and followed the Weber River as it paralleled the mountains to the west. Ahead, the Weber cut through a narrow impassible canyon with precipitous walls and the emigrants were blocked. Lansford Hastings, the dashing young guide who had promised to personally lead the emigrants, had failed to meet them as planned. He had pressed forward blindly with another group of emigrants. The shortcut over which they'd agonized back at the Little Sandy was virtually impassible. The Donner Party was on their own. Impossible as it looked, there was no other choice but to turn toward the omnious mountains and start up a side canyon. The struggle was unlike anything yet encountered on the journey. For the first time the wagons had to contend with forest of willows so thick they had to be cut and chopped one by one. For the first time they assaulted mountains straight on with no trail to follow. The slopes were so steep that at times for long stretches no ground could be found flat enough to allow a wagon to pass without toppling over. Somehow they struggled to the top.

The long arduous pull up a maintain range was rewarded by the most incredible and discouraging sight of the trip impenetrable wall upon wall of mountains yet to cross. The sight of deserts and plains was discouraging but crossing them ''merely'' required dogged plodding determination to just somehow keep going day after day after day. This mountainous spectacle, however, was horrifying. It actually looked impossible. The Donner Party [192] sagging among the lumbering wagons with no trail to follow, must have vomited with horror. It took them 17 days to hack through foot by foot, a miracle of accomplishment in itself. I would cross by road in a comparatively easy two. With a blazed trail they would have been able to do it in three.

We camped at East Canyon Reservoir, the same spot that we came to in 1976.

About 1 1/2 miles beyond East Canyon Reservoir, Cliff and I were enjoying the brief cool of morning and walking steadily. A car sped by ahead and Cliff said, "Hey Mom, what's that thing?" I looked up the road and about 50 yards ahead a large animal was casually relaxedly crossing the road in the wake of the vanishing car. Its languid graceful movements, its facial profile and tiny ears, its soft paws all said CAT, but its size was impossibly large. Cliff said, "Is it a Bobcat?" I said firmly, "no, too big." And Cliff said, "It's a mountain lion." It then, cat-like and with consummate grace, leaped over a barbed wire fence and disappeared into the brush and trees. I swore softly, "Holy dear God almighty, what WAS that?" Clearly it was a mountain lion. Our view had been too long and too close to doubt our vision, but I quickly ran through the reasons why it couldn't have been: 1) too close to civilization. It had stepped behind the car and in front of us. In fact, I immediately voiced a fear of rabies since its casual behavior had seemed so strange. 2) too unlikely in such a heavily hunted area. I couldn't imagine any living thing surviving the army of hunters we'd seen there 2 years ago. 3) too relaxed. It didn't live up to my image of the fearful hunted animal, tensely crouching and waiting and hiding and dashing in fear from place to place. But there it had been, clear unmistakable and unbelievable; but really there. Then I [193] searched for explanations: escaped from zoo? Someone's pet? Nope. Try as I might I couldn't refute my senses. We had seen a real mountain lion, a rare privilege. I kept looking over my shoulder - Attack? My senses said "no, of course not." My cowboy movie training said "watch out."

The Wahsatch reminded me of the Adirondacks in their jumbled contours. They're not laid out neatly as the Rockies but are a jumble of mountains and ridges and canyons running all at crazy and undecipherable angles. The Donners struggled through this maze half blindly, taking three weeks to hack and push through this tortured mess. We rapidly lost our comprehension of how anyone could do this in three years let alone three weeds, and after hours and hours of aching legs we reached the divide. And our route had been up a graded modern 1978 highway!

(They were to be by far the hardest mountains of the trip, barring the short impossible stretch in the Sierras at Donner Pass.)

A year later I returned to the Wahsatch. I stood and gazed again at those steep steep mountains. My eyes teared briefly. "How did they ever do it?" I whispered to the mountains yawning before me.

After weeks of heartbreaking toil in the cursed Wahsatch maze, with blind alleys, wrong turns and false illusions of shortcuts, the Donner Party halted for the night and a few climbed the h1l1 bordering the creek they were following.

The steep 300 foot hill emerged onto a barren plateau which dipped finally into the treeless valley below which stretched unhindered 25 miles to the Great Salt Lake shimmering in the distance. Below them in the tangled thicket of willows sat their 20 odd wagons by the little stream. The brook also emerged a short ways ahead onto the treeless plain but [194] that "short ways" looked like an eternity of hellish tree cutting misery to the bone weary emigrants. It is an eloquent measure of their advanced state of exhaustion that a desperate decision was made; they would try to scale the hill with the wagons and roll down the plateau without having to cut another tree.

The next morning it required every team of oxen hitched to every single wagon to accomplish the feat. Somehow they did it, but they had taken an awful risk. Any misstep would have meant injured animals and broken wagons. On the other hand it has been conjectured that perhaps they lost the gamble after all. Perhaps it was this near perpendicular 300 foot wall that pulled the hearts out of the oxen beyond recovery and set them staggering more dead than alive out onto the 500 miles of desert yet to cross.

Today the hill is distorted by utility buildings and a nearby modern apartment building. Those living in the building can gaze out on the unobstructed view that so lured the Donner Party, but today the treeless plain is the thriving bustling Salt Lake City. As I tried to picture oxen straining to keep their footing on the hill before me, a fashionable man walking his Dobermans strolled along the little stream bed.

A moment and plaque entitled Donner Hill sits vandalized at the base. The monument notes that one year later the Mormons, under the leadership of Brigham Young, cut through the willow thicket along the stream in only four hours. That Mormon vanguard had over 100 of the strongest select men of that entire religion at its disposal. There were less than a handful of women and children in the Mormon group. Brigham Young's contingent had rolled in on the trail that the Donner Party had blazed with their pitiful weakened crew of less than 27 men, many old and feeble or sick. The Donner decision to scale the wall could only have been taken out of desperation, certainly not from laziness or stupidity. [195]

It was almost time for my family to leave me. The kids had taken turns walking with me. Each walked at least 100 males. I had spent hours and hours alone with each. These were virtually the only times in our lives when we had each others undivided attention for such long periods of time. There were no legions of dishes to do, appointments to keep, house cleaning, or books waiting to be read, newspapers to catch up on and no phones ringing. It was just the two of us walking forever across endless sage range. Paula chattered ceaselessly with her thoughtful creative energy. Cliff was more circumspect; his sentences carrying the weight of one who uses words sparingly. The kids shared each other. We shared the heat and the antelope, stores and tired legs. We shared short tempers and shooting stars. We shared the Trail. And when it was over the kids were still not particularly impressed with my venture. It was not quite the warm family scene that people pictured when I’d say, "My family walked part of the way with me." But it was good. I'm glad they were part of it, and I couldn’t have done those desolate stretches without them.

It was almost time for my family to leave me. The kids had taken turns walking with me. Each walked at least 100 males. I had spent hours and hours alone with each. These were virtually the only times in our lives when we had each others undivided attention for such long periods of time. There were no legions of dishes to do, appointments to keep, house cleaning, or books waiting to be read, newspapers to catch up on and no phones ringing. It was just the two of us walking forever across endless sage range. Paula chattered ceaselessly with her thoughtful creative energy. Cliff was more circumspect; his sentences carrying the weight of one who uses words sparingly. The kids shared each other. We shared the heat and the antelope, stores and tired legs. We shared short tempers and shooting stars. We shared the Trail. And when it was over the kids were still not particularly impressed with my venture. It was not quite the warm family scene that people pictured when I’d say, "My family walked part of the way with me." But it was good. I'm glad they were part of it, and I couldn’t have done those desolate stretches without them.

Next morning Howard dropped me off on the Watsatch divide before sunrise in incredible windy cold after a day in the 100's! I cried. Howard cried. Later he returned with kids. Paula gave me a beautiful hawk feather she'd found on the trail for good luck, and I cried again. Quickly the little red car was gone. I raced 24 miles into the city to get my room at the "y" before 1 PM. Today my feet and legs are very, very lame. I must put a search on for vitamins something drastically wrong with my recovery rate.

I love the “Y.” en’t pened it yet. Strange mixture of women, unwed pregnant, battere recovering surgery, old, young, foreign, hookers, blind, retarde I almost guilty of being so well off, so I [196] bought a membership.

I wanted to stay on the Donner schedule as well as on their trail. Their three week struggle through the Wahsatch compared with my two days set me way ahead. So I decided to stay at the YWCA for a couple of weeks. Immediately I was faced with a problem that had been pursuing me relentlessly for weeks; my money was running low. After avoiding the inevitable for a few days, I finally faced myself, ignored my embarrassment and self consciousness and went looking for a job.

For two weeks my trail mentality would be shelved as I readjusted from the empty wagon ruts of Wyoming to the press and stress of big city living. The contrasts couldn't have been more vivid.

I went to a temporary job service and sat briefly among some scruffy looking fellow job seekers. I wore my trail ravaged clothes but somehow still feel that I fit in with the group. Within 30 minutes I was offered 3 jobs: secretary, maid or production work. I chose production work and, after catching the bus outside, was working within a half hour, minimum wage $2.65 per hour, in a clanging banging, chop chop, whir, squeal, screech, grinding factory, making and packing surgical masks. I felt I was out of my element but was determined to fit into the job, so I applied myself diligently. All my old sociology courses and academic snob analyses hung in the back of my mind, the demeaning, dehumanizing, deadening qualities of repetitive factory jobs, sapping one's vitality, etc., etc. "Hey!" I thought, "That was all balony! This is terrific!" as I assembled, glued, stuffed and packed box after box. "Why, this is even fun! Not hard, even satisfying!" I worked fast and tried to be a model of efficiency, ever the good little girl seeking gold stars. Then I remembered the academic studies that showed the system of the unspoken code of the workers: don't rock the boat by work- [197] ing too fast and productively, so I slowed down to what I guessed was a moderate fellow worker accepted pace. But good little girls don't disappear that fast, so I worked through my coffee breaks and my lunch break. Some- where between 3 and 5 hours the early conclusions about work speed became theoretical as I had burned myself out in the first three hours and my 1200 mile feet began to ache and my back wanted to lie down and my mind screamed for a rest, ahhh sleep. The hours which had slipped by so easily earlier suddenly froze, and every five minutes took forever. I felt trapped and defeated, one and a half more hours to go and I summoned up some grit and hung in there to the end, when I limped (sore and fatigued) to the bus. Oh yes, my grand pay? $17.23.

The busses kept turning before they reached me and I repeatedly inquired if this was really the bus stop. It was. So I sat and broiled and seethed and stressed in the oven-like supper time evening rush sun. After an hour a bus came and I got on. This was harder than walking 30 miles of trail any day!

Back at the "Y" I was handed a sheaf of messages from media people.

There it goes again, the roller coaster effect, from beaten haggard minimum wage assembly line factory worker to media star, all in one day!

There it goes again, the roller coaster effect, from beaten haggard minimum wage assembly line factory worker to media star, all in one day!

Friday at work was a robot torture day, no desire to set new records enlivened it.

After a week's factory work I was beaten and drained. I could feel fatigue distorting my face, a fatigue that has a different quality from the fatigue of a long day on the trail. My eyes were expressionless and a heavy drooping sensation pulled down on my facial muscles. I had a weak impulse to say a nice thing to the sad person next to me of the bus, but the [198] impulse drowned in exhaustion. It was a deadening life.

Just as much as I love the majestic feeling of being alone in the wilderness, I also love the excitement and people mixture of a big city. But coming in fresh from the clean health promoting trail, I saw city life with sad new eyes. City stress was everywhere, in complicated bus schedules, in bungled phone messages, in long lines at the checkout counter in thousands of tense and sallow faces, in shrill and sobbing children, in obese bodies straining to hoist themselves up stairs.

One evening after work I helped a young woman find her way across town to a hospital clinic. Mary had behaved strangely on the way in the bus. She laughed hysterically at inappropriate things (the sound of the money dropping into the coin collector) and she became agitated over peculiar things, (whether or not the traffic light would change before our bus reached it). In retrospect, I must admit with shame that her odd behavior was an acute annoyance to me. At the hospital she was led by a nurse into the examining room to see the doctor. I waited for her to emerge with medicine for her sore throat. Past midnight, five hours later I was still waiting. The nurse approached to question me. Mary's strange behavior had so alarmed the doctor that she was being evaluated by a psychiatrist. In the early hours of the morning Mary was released to return to her temporary home, the YWCA. Alone in the big strange city, looking for her lost baby (her husband had taken it away) Mary was having a nervous breakdown.

Every day for the 5:37 bus a woman waited eagerly on the corner of 78th Street. As the bus approached she would strain to see through the windshield if the driver that day would be Ronald. On Thursday her face [199]

lighted when she recognized him. He ignored her as usual as she dropped her fare into the money machine. She sat in the front seat across from him. She ran a comb through her wispy brown hair her eyes still on Ronald. She hoisted a large tape recorder onto the seat and flipped the switch. The bus carried the quivering sugared tones of an electric ukuele. With a shy yet determined look, the woman rummaged in her large bag and pulled out the final prop, a huge Hawaiian lei made of shiny pink plastic flowers. She arranged this carefully, draping it over her shoulders and pulled the strands of her thin brown hair forward. She waited her pleading wistful eyes never leaving Ronald. She turned the music up a bit and waited some more, ''lovely hula hands, graceful......" The bus route ended. The woman packed up her tape recorder. She took off the enormous plastic pink lei and put it back in the bag and climbed off the bus with the rest of us. Ronald never looked up. I wanted to tell her that 1 enjoyed her music but I didn't.

lighted when she recognized him. He ignored her as usual as she dropped her fare into the money machine. She sat in the front seat across from him. She ran a comb through her wispy brown hair her eyes still on Ronald. She hoisted a large tape recorder onto the seat and flipped the switch. The bus carried the quivering sugared tones of an electric ukuele. With a shy yet determined look, the woman rummaged in her large bag and pulled out the final prop, a huge Hawaiian lei made of shiny pink plastic flowers. She arranged this carefully, draping it over her shoulders and pulled the strands of her thin brown hair forward. She waited her pleading wistful eyes never leaving Ronald. She turned the music up a bit and waited some more, ''lovely hula hands, graceful......" The bus route ended. The woman packed up her tape recorder. She took off the enormous plastic pink lei and put it back in the bag and climbed off the bus with the rest of us. Ronald never looked up. I wanted to tell her that 1 enjoyed her music but I didn't.

Walking to the food store yesterday I passed drunks asleep on the curb,

a puddle of blood where an old lady had fallen and the overpowering stench of urine by the phone booth; the pee was in the newspaper vendor next to the phone.

a puddle of blood where an old lady had fallen and the overpowering stench of urine by the phone booth; the pee was in the newspaper vendor next to the phone.

At work a young woman got her middle finger chopped off in one of the machines. I held the chopped off finger stub tightly to stop the squirting blood and her cool gray-blue detached chopped finger in my other hand. They sewed it back on at the emergency room.

One day in the crowded bus station I was watching an exhausted woman with six young children coping patiently with one baby in her arms, another sleeping in a pack on her back and four others crying or lying on the dirty [200] bus station floor eating candy. An old lady offered kindly to hold one of the babies. The scene was abruptly interrupted when from the far side of the waiting room a well dressed, very handsome athletic looking man began shouting and stomping in an unearthly authoritative voice, "GAMES! NO MORE GAMES!! ALL YOU PEOPLE STOP PLAYING GAMES!" He strode through the terrified hushed crowd with an air of barely controlled violence. The two frightened ticket salesmen marched up from behind, each firmly grabbing an arm and ushered him outside. The scene had suddenly rocketed everyone of us in the crowd out of our normal and varied preoccupations, everyone of us, that is, except the one sleeping baby. We all remained motionless and stunned for a few eternal seconds.

The berserk man returned a few minutes later, a changed and now sane but pale expression on his face. A muscle throbbed rythmically on his temple.

He purposefully walked here and there about the station as people averted their eyes. He walked out of sight into a side room. In about 20 minutes, he emerged looking upset and tense, but with charisma and infinite self control, apologized individually to everyone in the bus station going from person to person with extended hand saying quietly, "thank you for understanding.'' I appreciate your understanding." "Thank you sir.'' "Thank you madam." "Thank you for understandingly." Then he left. I had wanted to communicate something to him, but my fleeting chance had passed.

What had happened? Could it have been a Vietnam flashback? A bad drug trip? An LSD flashback? A nervous breakdown? A weird experiment in social psychology? The man had emanated something special in carriage and manner: mysterious and fascinating, insane one minute and showing exceptional poise the next.

There were three beds in my room at the "Y". I had a steady stream of [201] roomates. One day I dragged my weary self home from the factory and the operator in the lobby stopped me. “Barbara, this is Dorothy. She'll be staying in your room tonight.” Dorothy hovered like an emaciated wraith in the corner of the lobby. She had the thinnest head and the sallowest face I ever saw. On her hunched and motionless frame hung an exquisite white dress, almost a bridal type of gown. Two suitcases seemed to stretch her long thin arms nearly to the floor. I led her to our room. She stood mute and expressionless. “You can sit down, Dorothy. Make yourself at home.” Dorothy stood motionless. "Dorothy, sit down, '' I said rather firmly.

Bit by bit I extracted Dorothy's monotone story. Dorothy lived in the Bronx in New York City. She was from an old world ethnic family. She had been extremely sheltered all her 22 year life. Her family fairly adored, even worshipped, the Osmonds singing group, especially Donny and Marie. (At that point I had scarcely heard of then leading one to wonder who was more out of the mainstream, Dorothy or me!) Her family although poor, had scrimped and saved to buy a plane ticket, a new white dress and presents for Dorothy to deliver to the Osmond family. "The cops" had picked up Dorothy wandering aimlessly and lost in the Salt Lake City airport and had delivered her to the "Y" to the "women in jeopardy'' program. Indeed, this surely was one woman in need of help! Dorothy opened her suitcase and sure enough, there they were, presents, a suitcase full of them for the Osmond family. The next morning I took Dorothy to the Travelers Aid office where a kind and amazed social worker took the problem in hand. When I left, a bewildered Dorothy was sitting like a haunted statue in a chair while effort was being made to at least get her to a recording session of the rich and powerful Osmonds.

Helen stayed in "my" room one night. She had a black eye and a swollen face. Her husband had beaten her again. She was slowly losing sight in one [202] eye from the beatings. “I begged him, 'honey, if you think I'm bad and need to be hit, then please hit me on my rear where it won 't show.' But he always goes for my face, and then I have to miss work.” It was Helen's fourth marriage. This was the only husband who had ever hit her. The second husband had divorced his abnormal wife to marry Helen when she had weighed 340 lbs. “He must have been a real winner too,” I thought with grim sarcasm. Helen was waging a terrible internal struggle, fighting the temptation to go back to her violent husband. When I returned from work the next day I found a note on my bed. “Goodbye, my friend Barbara. I am on my way to Arizona. I think I'm going to make it this time. Love, Helen." I hope she made it. Somehow I think she did.

In the past it had been so easy to overlook the casualities of the city life. Here for a while that was all I could see. I was appalled at tie obvious poor health of those around me. Having just walked through the rosy cheeked ranch and farm population, the human condition in the city seemed all the more tragic. The distinctly different body odors, the rotting crooked teeth, the style and colors of the clothing, the pasty skin, the stringy hair, oily and dark near the scalp, brittle dry and light near some ends, the expression in eyes. Looking for simple solutions I pounced on the poor American diet as the culprit. My journal fairly steams with indignation.

I'm appalled at the realization of how utterly sickening, weakening is the American diet, and the poor people seem drawn to its very worst elements. Is there a conspiracy somewhere to dominate the market with these sickening products? (The old American solutions: form a committee and look for a conspiracy!) One must struggle to eat or even find decent food. The whole factory where I work is hooked on Coke and soda and horrible vending machine [203] candy. Garbage and worse, all of it! Sugar and chemicals, sugar addicts.

unhealthy people, weak, sick, fat, pouring this horrible stuff into already debilitated bodies. Who is it that floods the media this week with warnings about hazards of drinking too much milk or eating too many eggs while the Coca-Cola pipeline is pumping chemical sugars into protein starved gullets unchecked? The government and media chortle about how health foods are rip-offs. Is there any bigger rip-off in this country than $.25 for a Milky Way which has no redeeming food value at any price? In the middle of a busy day at the factory, it is impossible to find decent food, yet the vending machines surround one's growling stomach with sugar and salt in every chemical form and flavor. No wonder the rural farm families seemed younger and healthier than their years, fresh eggs, meat, milk and the backyard vegetable garden! Now I am on the rampage!

unhealthy people, weak, sick, fat, pouring this horrible stuff into already debilitated bodies. Who is it that floods the media this week with warnings about hazards of drinking too much milk or eating too many eggs while the Coca-Cola pipeline is pumping chemical sugars into protein starved gullets unchecked? The government and media chortle about how health foods are rip-offs. Is there any bigger rip-off in this country than $.25 for a Milky Way which has no redeeming food value at any price? In the middle of a busy day at the factory, it is impossible to find decent food, yet the vending machines surround one's growling stomach with sugar and salt in every chemical form and flavor. No wonder the rural farm families seemed younger and healthier than their years, fresh eggs, meat, milk and the backyard vegetable garden! Now I am on the rampage!

This morning at the "Y" ate breakfast with a young woman, vivacious and attractive with a neck brace, nose patch and covered with bruises. She'd been raped a week ago after hitchhiking. Another woman, an attractive 40 year old nurse, had been raped at age 19. The young woman said, "Of course I'll continue to hitchhike; in fact, I have since. I felt I had to. It's like getting back on a horse after being thrown. It's a way of life for me, and I meet so many people."

I said, "People expect women to cloister themselves for life and that's unfair." The older woman said, "Look at me. It's been all these years, 20, since I was 19 and nothing has happened to me since."

In that brief conversation I learned 2 things. 1) Every woman must draw her own rules and lines about how she is to live. I will never hitchhike, but more power to those who do, who, as these women, do so with real [204] (too real ) knowledge of the risks. 2) My 2,000 mile walk is a baby step as far as subjecting myself to risk. Woman do more "brave" living than this commonly year after year. I just haven't until now run into them.

But there was also inspiration in Salt Lake City. The Mormon history, if nothing else, demonstrates the Herculean problems that a determined populace can surmount.

I have an unquenchable thirst for being bowled over again and again by the feats of the Mormon pioneers. The bare facts of their early accomplishments seem to put them out of the class of ordinary mortals. Persecuted and driven, they died by the hundreds, yet they managed to escape to this godforsaken desert, make it "bloom like a rose," erect a tabernacle and begin work on a temple that still awes, lay out plans for a city that had 100 years foresight all within 2 or 3 years. They combined the back-breaking toughness of the crudest muscled pioneer, the genius of the NASA lab scientist and the refinement of the most cultured Bostonian. In the old civic building, matching in elegance the finest furniture in the Louvre one can see even today the old richly carved piano that was brought with the first group across the plains in a wagon.

I heard a free organ recital in the tabernacle. Built by the pioneers, the tabernacle remains one of the great buildings of the world, all of wood, held together with pegs and leather thongs, acoustically considered supreme, housing one of the world's great organs, seating 6,000 intimately and cozily. One can feel the vibrations of greatness and history there. [205]

--- ? ---

Unfortunately, next to the dignified and inspired tabernacle stand two modern visitor's propaganda centers. Although herded and guided by attractive and poised Mormons, the centers degenerate rapidly into simplistic, sentimental Disney style gimmickry. They reminded me of the red spray paint next to the elegant granite chinlings on Independence Rock.

While waiting for the cafeteria to open, the "Y" women often gather in the lounge to watch the evening news. On August 15 the news switched to a boat off the coast of Florida where the young woman Diana Nyad was making her well publicized bid to swim from _____??____

I detected then and since a great antipathy toward her, generated, I assume, by her vigorous self promotion. It rubs against the grain of our image of the modest self effacing woman. But tonight Diana was failing in her attempt at greatness. I'm afraid that many people were smugly satisfied at her failure. ''It served her right for being so commercial." But there in the "Y" lounge we all saw just a woman like us trying desperately hard to achieve something important to her. We saw her vomit in the water while [206] trying to keep swimming. As she put forth the ultimate in effort and failed, we did not separate from her, we joined her. There went up a universal agonized sigh when she was pulled from the water. I was proud of us all at the "Y". My eyes were wet. That night I dreamed of her struggle.

I was in my own struggle that was important to me. I did not feel competitive with her. Somehow I felt we were on the same team, and in a way her loss was all of ours.

Today talked to a newspaper reporter. She asked thorough questions. I went into my "Good American People" theme. On leaving she said she hopes the publicity will bring me no kooks or harm. I said, "It brings out the good people.

She said, "we can hope that maybe only 1 out of 10 will be bad."

I said, "no, only one out of a million is bad." And that points out the pervasive attitude (even in the wake of my strenuous speech) that the world is very dangerous, strangers likely evil, etc.

A TV reporter, Adelle Tyree, and a cameraman walked with me for about 9 miles west of Salt Lake City. While walking together, Adelle and I talked opening and intimately about everything from women's lib to Mormons. There was an unusual rapport, instantaneous and complete. Unlike most conversations this was balanced, neither of us dominant, but both of us taut with the excitement of sharing, expressing and receiving each other's opinions and emotions. Near the end of our walk together, Adelle interviewed me for TV by the edge of the highway. She gazed directly and intently into my eyes and asked deep and thoughtful questions. I put all of myself into answering her as truthfully and deeply as I could. The cameraman filmed a “farewell” scene and Adelle and I awkwardly but with mutual impulse [207] embraced each other. Adelle said "Barbara, I like you." The cameraman had ''technical difficulties'' so we filmed the ''farewell'' again (more polished this time!).

Adelle is a professional reporter. She pulled from me the best interview I have ever given. She worked for it; prepared thoughtful questions, established a rapport with me, and yet nothing on earth can shake my faith that our brief sparking relationship was genuine all the way.

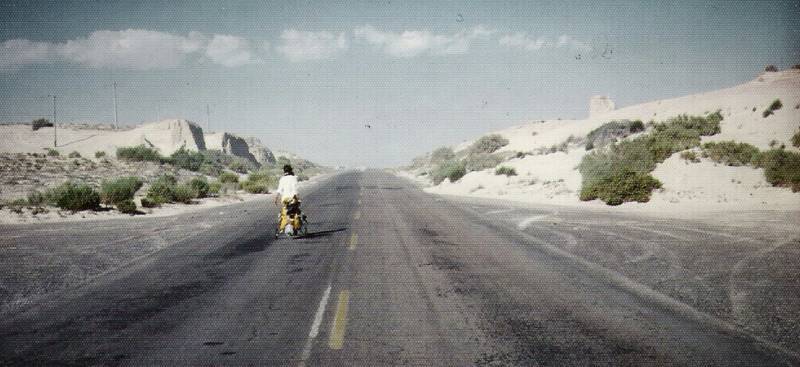

Somehow it felt like Salt Lake City should be the end of my journey. I had absorbed all the experiences I thought I could hold and 1,200 miles seemed like enough journeying for any pioneers. But a quick look at any map showed I had come incredibly only a bit over half way. Ahead loomed the deserts; the scariest of all would come first, the Great Salt Desert. A newspaper article about me had brought a flurry of telephone messages piling up at the front desk warning me of the terrible dangers of the desert.

A dazzling creative woman named Karen (who had forthrightly summoned the press on my arrival) presented me with a creation that she had whipped up. It was a concoction of white sheets and silver mylar for my ''dangerous'' desert crossing. The silver layers were to reflect heat and make shade (which they did very well) and to use later in the snowy mountains to reflect heat inward (which they also did very well). The layers of sheets had brilliant orange sparkle words printed on them in huge letters. One word was my name, MAAT, to signal the helicopter search parties that I was OK and the other message was SOS to signal for rescue. She had notified and inquired of all sorts of officials (like jeep posses!) and rattled off assorted facts to me about sand temperatures, salt requirements and desert water collectors. With a “can do” person like Karen behind me, how could I [208] fail! Her friend Bill made a packet of bullion, sugar, tea and assorted goodies that he estimated would keep me alive for 10 days in a pinch. I accepted Karen's and Bill's thoughtful serious gifts and found room somehow to add them to pack on my groaning golf cart.

That was not the end of my safety equipment, however; a very official intimidating military car pulled in front of me soon after I was under way. My paranoia flared and I braced for a lecture and prohibition about walking the desert. (I had already heard about the miles and miles of military test site with the thousands of rounds of live ammunition peppering the innocent looking sands.) Out stepped two men in military regalia who stood before me and all but saluted. To my utter astonishment, they rather formally (and somewhat bashfully) presented me with a heavy ammunition bag stuffed full with more safety equipment: smoke flares for the day, fire flares for the night, matches that would burn in 50 mph wind, mirror signal devices for search planes, tarps for water stills, charts of distress codes for signal flags, and lots of other little weighty goodies. I was overwhelmed with the unexpected thoughtfulness. Whoever heard of the U.S. military whose image to me was one of beaurocratic inefficiency and snarls of red tape managing this little quirk of kindness! Surely it is not covered in any of the procedures manuals! Somewhat nonplussed I stammered my thanks rather foolishly and then said earnestly, “Please rest assured that I am not going to do anything dangerous that would require any possible inconvenience of search and rescue by anyone. I'll be within sight 1-80 all the way. I'm doing this trip for experience but never never for narrow escapes.” Then I added, "Gee whiz with all this safety equipment you'll make me feel that somehow maybe I OUGHT to try something a bit more dangerous!” “My God,” I thought, “was I letting someone down? Were people expecting me to risk myself in hairsbreadth escapes with my [209] life?" My trip carried no such image to me.

The kind officer and sergeant shook my hand positive and supportive and drove away. I stood by the roadside searching my already overloaded cart for another spot to tie on some more safety equipment. ''My safety equipment," I mused with irony, "will do me in yet!" The extra weight was wearing my axles thin and was wearing me out. I might be better carrying extra water. But my policy, perhaps superstition, was firm; anything given to me out of kindness would never kill me and I would carry it all the way no matter what. The power of kindness was the greatest fuel I'd found yet. ''But where, oh where was the ammunition bag going to go?!'' With an anxious chuckle I turned and walked on carrying it in my free hand. Laden down with my safety equipment!

It was the middle of August. I looked back at the city that had been my home for two weeks. The backdrop of the Wahsatch Mountains was topped generously with freshly fallen snow, and yet I was already well out onto the scorching hot desert. Only in the west could the paradoxes come so frequently. I was mentally shifting gears, getting into my "alert for any contingency" frame of mind that went with my "woman alone on the highway" situation. It was a stress that I carried along with me all the way. Sometimes I scarcely knew I carried it; sometimes, especially early in the trip, it dominated me. Probably none of it was necessary.

I also had to shift gears with my sense of time and distance. There was no sense in trying to rush toward the landmark ahead. It was still four miles ahead to the edge of the Great Salt Lake campground, and four miles took over an hour regardless how fast my mind raced or how impatiently I strained. Finally after an eternity of city tense anticipation, I lowered myself into the skimpy shade cast by the public restroom. I had forgotten [210] how weary my bones could feel. I would have to get used to this again too.

The families of George and Jacob Donner represented well to do respectability and responsibility. Tamsen Donner, an educated woman, had plans to start a women's academy in California for the benefit of her daughters and others. George the Captain of the train and Tamsen were solid people, the kind who brought civilization to the west. It was only natural that they took in Luke Halloran, a consumptive, traveling alone with the train. Tamsen nursed the sick young man but within two days after escaping the clutches of the deadly Wahsatch, Luke Halloran died. Out of respect for his death the emigrants who had shunned a day's rest after their escape from the mountains paused one day. "When you throw bread on the waters, it comes back to you" insists a successful businessman I know. Maybe so; after he died, he was found to have carried $1,500 in coins that he willed to the Donners on his sick bed.

Despite the horrors of the trip so far the emigrants by this simple gesture gave testimony that they were still a viable functioning unit practicing the accepted civilized decorum of the day. Later, in Nevada, their common standards of decency would begin to crumble under the stress of their increasingly desperate situation.

At night by the Great Salt Lake it actually became cold (jacket) and very windy. The wind blew hard and a splattering noise and feeling covered the windy side of me. I thought it was sand and salt and then rain drips, but when I looked down I was amazed. I was thoroughly speckled with black dots, crawling bugs. They would be blown against me and stick; face, jacket, pants, etc., thousands of them, and then I realized that in the twilight I had been eating them in the beans. [211]

A storm s seemed to be brewing. So I dragged the picnic table to some sand (away from the sea of boulders) and weighted some plastic on the top with rocks. I pulled 2 garbage cans to the windy side and squeezed under the table into my bag, looking like a bum in a garbage dump. The wind had blown sand into my bag and the bugs were speckling everything. I raised my head, brushed the bugs from my "pillow" and quickly put down my head to avoid squashing bugs, then pulled the bag around my neck to keep out more sand and bugs and went to sleep; sand collecting on me like snow.

The other tents around me blew down but I slept well enough through the tumult, once again proving mind over matter. In the morning the wind was gone and the mosquitoes were out and the stench from the garbage cans all too apparent. When I rolled up my sleeping bag, I found that the garbage cans weren't the only objects emanating stench; there was a dead rat in my sleeping bag. Its rotting entrails had smeared between the bag and the groundcover and I had slumbered oblivious and peaceful during the night. A string of bad luck quickly followed. I could not find my food bag and assumed (mistakenly as it later turned out) that someone had stolen it. The bathroom and water supply were locked. Sometime during the walk the day before, I had lost one of my wineskin water containers. I check my golf cart and noticed with horror that my axle was virtually worn through. So I headed toward the little village of Grantsville, with a smelly sleeping bag, thirsty, hungry (thinking of the food I had overbought the day before and had given away to lighten my load) and with a wary eye on my thread thin cart axle.

Then on the way to Grantsville a man in a dump truck motioned slyly for me to go to him. I did and he talked silkily about wanting "a chance to get to know me" and I said there was no chance. He was the very first obvious skunk to try to pick me up. Later a car of young men careened past and tried to scare me (I was startled and annoyed) by leaning out and [212] screaming at me while banging on the car door. Three people with wormy dispositions and cesspool brains in quick succession unfairly, but inevitably colored my impressions of all of the Salt Lake City area. It's amazing how a few incidents, good or bad, can leave an impression of a whole area.

Then, magically my luck changed. Two men in a cafe were very nice; they'd seen me on TV, and then I became aware that the kitchen help and people all over the cafe were recognizing me. When I left, people waved or stopped or called "good luck". One man got a camera and returned. Then the senior citizen van returned from distant Grantsville and delivered a hot lunch.

Approaching Grantsville, people emerged; the reporter from the paper, friendly townspeople, the city councilman, people with cameras and pictures for me to autograph. At the city hall, people crowded in to see me. I was tired and dazed but found myself escorted to the local Donner museum, which was unlocked for me. A wonderful Mormon family opened their home to me; another gave me $5 for courage. It had been a full and long 20 miles from the dead rat in my sleeping bag so long ago that morning, to the safety and goodwill that the people of Grantsville extended. [213]

Great Salt Desert - original trip

Original trip

original trip

Knolls

Wendover marked the end of the Salt Flats and the start of Nevada