CHAPTER 6

KANSAS

May 7 – 18

(119 miles)

KANSAS

May 7 – 18

(119 miles)

It was only my 10th day and 97th mile on the trail.

The days and miles began to pile upon themselves as my journal reflects the steady monotonous litany of pain. Incredibly, I kept going under the naive assumption that I would soon trail toughen despite every objective indication that my feet were getting worse. Little did I dream then that it would be full 400 miles before the condition of my tortured feet was not the dominant, unrelenting factor of my existence.

Despite the pain (and maybe even because of its effect of heightening my sensitivity) I found each day offered up adventures and experiences I would treasure forever. I write “each day” with careful awareness of its precise meaning. There was never a single day I would have done without. How different from my past life when whole weeks, even months passed at times without leaving a retrievable memory! When people have said, “How could you take the time out of your life to do this?, I respond that “so far this venture was not ‘out of’ my life, but rather the heart and core of my life.” But back then it was just the beginning. . . .

Some of my journal entries are now humorous to me, some educational, some heart warming. I first encountered a snake theme even before the trip began. “My God! What are you going to do about snakes?” It hit me again only the second day out when the mushroom hunter lady crept fearfully with her snake weapon. In the Topeka motel I overheard a man outside my window, “I was cleaning out his hollow yesterday and found a cotton mouth.” Another man answered “Yeah? Did you hear about Bill Marley? He got bit by a Copperhead last week.” I was to venture forth next day with every intention of camping out in this snake haven. O h well. . . .I sighed again. But that was not to be the last of the snake theme. It would in fact plague and pursue me steadily across the entire country. There were times when it seemed to be the major preoccupation of the entire country. There were times when it seemed to be the major preoccupation of the entire populous. Old men in cafes would invariably bring it up sooner or later among themselves. Tall tales would spin around my worried eavesdropping ears until I felt for all the world like David going out to meet Goliath the snake.

But this day I was to cross the Kaw (Kansas River). It was an early milestone for the pioneers for whom it was often a terrifying experience. For me too, it was not without its excitement. “I crossed the Kaw on a super highway bridge and because there was no walkway I walked on the side ledge with the guard rail barely thigh high. The wind gusted, a big truck hit a bump, the bridge bounded wildly and I felt like the great Wallenda (famous tightrope walker), nearly, or so it felt, pitching into the muddy river far below. From there, on I took my chances down on the pavement with the traffic. THAT’S what I probably should worry about anyway!!

It was a memorable day for Kansas beauty. The sky was blue with miles and miles or orderly fluffy white clouds. The rains had softened the ground to a perfect cushion. The shiny green ribbon grasses (wheat) shimmered and waved in the cool breeze, heaven, heaven, heaven. I was elated about life in general, and of course, overdid it, walking 17 miles to Rossville.

I stopped for help in the local high school where some clear-eyed poised teenagers greeted me without suspicion. A young teacher, Steve Lewis, quickly invited me to his place for the night. Embarrassingly I was actually unable to lift my heavy pack into his pickup truck. We bounced along in the beat up camper across the farm lands toward the old farmhouse Steve and his wife Laurel were restoring. I could see it, a little dot across the fields as we approached. An old dream of mine was about to come true. Ever since my first trip out of the east in 1965, I’ve been intrigued by farm houses which seem like little treed island oases in vast seas of crops stretching away in every direction. How often I had wondered what it would be like to be inside such a haven looking outward! My old wish was to be rewarded and what a reward it would be!

On the way Steve said, “Often fantasize that this dirt road of mine was the old trail and I can’t tell you how many times I’ve marveled and wondered trying to imagine how the pioneers coped with the weather.” He broke off wondering and swerved sharply to avoid a deep rut left over from the last rain storm. But today already the drying sun was starting to turn the old road into a dust hazard. Mud and dust, the pioneers were all too familiar with both conditions”

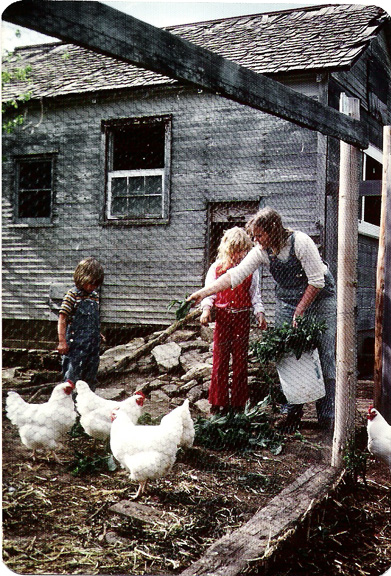

The Lewis’ farm house was every inch a romantic, idyllic, old fashioned movie set. Out comes the young plumping wife with baby to greet husband, long rows of flowers, iris, blooming in broad garden across the front yard, swing on a long rope from high on the shade tree limb, flock of chickens, red barn, freshly planted vegetable garden, endless flat plowed cornfields stretching away from the house on three side, rolling pasture lands on the fourth side. Then a little girl runs up to her daddy and we go inside, boot rack on porch, flowers around back door, clothes line and bright clothes flapping in the breeze, tiny orchard, sand box, friendly dog running up with ball, bird houses. In the kitchen hard wood floor, old wood burning stove with herbs hanging and drying about it, fresh cut flowers in center of round table, old fashioned variety of chairs, old paddle butter churn, old tiffany lamp on the table and on and on everywhere. Gingham curtains, cradle next to bed, freshly baked cookies brimming over in the cookie jar, fragrant spices, coffee, flowers, and cookies. Every room was more dripping and unpretentious charm than the one before, needle work, patterned strawberry wallpaper.

The Lewis’ farm house was every inch a romantic, idyllic, old fashioned movie set. Out comes the young plumping wife with baby to greet husband, long rows of flowers, iris, blooming in broad garden across the front yard, swing on a long rope from high on the shade tree limb, flock of chickens, red barn, freshly planted vegetable garden, endless flat plowed cornfields stretching away from the house on three side, rolling pasture lands on the fourth side. Then a little girl runs up to her daddy and we go inside, boot rack on porch, flowers around back door, clothes line and bright clothes flapping in the breeze, tiny orchard, sand box, friendly dog running up with ball, bird houses. In the kitchen hard wood floor, old wood burning stove with herbs hanging and drying about it, fresh cut flowers in center of round table, old fashioned variety of chairs, old paddle butter churn, old tiffany lamp on the table and on and on everywhere. Gingham curtains, cradle next to bed, freshly baked cookies brimming over in the cookie jar, fragrant spices, coffee, flowers, and cookies. Every room was more dripping and unpretentious charm than the one before, needle work, patterned strawberry wallpaper.

In the midst of all this, Laurel was suffering a bit from an overdose of housewife syndrome, 24 hours a day mothering, farm isolation, etc. Steve was starting a chimney sweep business.

Steve and Laurel have had pigs, goats, bees, and chickens plus everything in the vegetable garden. Laurel has a ready market for everything in town because even though it’s a farming area, the women who used to do gardening and barn chores for extra money now work in the towns at money jobs.

For supper we had pancakes with sausage from their pigs and homemade elderberry syrup.

Next morning Laurel gave me a fragment of a china doll they had found while digging on their property. She said ”Here, I want you to carry this. It came from the trail and was probably meant to go on.” It stayed with me the whole way.

I left Rossville in the morning sunshine, bathed in the warmth and beauty of the people and farm and life I had shared for a few hours. Miles and hours of cornfields beneath my feet and eyes. I clung to the sweet memories all the harder as the unmistakable daily cycle of foot pain intensified. My yearnings for peace grew with every futile and desperate change of shoes and socks and back again. Finally I walked into the little village of St, Marys and suddenly after miles of empty fields and hostile heat, suddenly I was floating down tree shaded streets with early century houses gleamingly painted white, quaint lovely architecture, small flowered hedged yards, perfumed lilacs, neat sidewalks. An old Catholic mission, almost out of place in its grandeur and patient quiet elegance loomed graciously beside a tiny moss walled brook which was bridged by a ferny walk. Vivid patches of sunshine dappled the cool dark shade. I nearly wept with the beauty.

I left Rossville in the morning sunshine, bathed in the warmth and beauty of the people and farm and life I had shared for a few hours. Miles and hours of cornfields beneath my feet and eyes. I clung to the sweet memories all the harder as the unmistakable daily cycle of foot pain intensified. My yearnings for peace grew with every futile and desperate change of shoes and socks and back again. Finally I walked into the little village of St, Marys and suddenly after miles of empty fields and hostile heat, suddenly I was floating down tree shaded streets with early century houses gleamingly painted white, quaint lovely architecture, small flowered hedged yards, perfumed lilacs, neat sidewalks. An old Catholic mission, almost out of place in its grandeur and patient quiet elegance loomed graciously beside a tiny moss walled brook which was bridged by a ferny walk. Vivid patches of sunshine dappled the cool dark shade. I nearly wept with the beauty.

Two teenage girls approached and expressed friendly curiosity about “what are you doing?” Before they had the words out I had plunked down on the ground and peeled my socks and launched into a long explanations about each blister and bruise. Only later did I realize that my frantic explanations were hardly relevant to their question. Later that afternoon with St. Marys far behind, the two girls drove out to find me, with kindly concern to check on my progress. I carry fine impressions of St. Marys.

Toward evening, near tears with pain, I stopped for water at a farmhouse and was met by a very proper grandmother and her two grandchildren. Before the first sentence was uttered, once again like a robot, there I was on the ground peeling off socks and pointing out blisters and swollen crooked toe nails in a compulsive mindless torrent of words! My left foot pinky was a pale white fluid balloon with a tiny dot indentation which was a toe nail. On and on I rambled utterly daffy. Only later was I to recall the startled puzzled expressions on the faces of the perfect strangers I accosted with my foot blather. The grandmother was moved to bring me some Mercurochrome and antibiotic salve from her medicine cabinet. She responded quickly as if an emergency had hit. Her concern, if not her salve, saved my day.

I limped on a final 2 1/2 miles to an old Indian pioneer cholera burial ground. A forlorn abandoned homestead was the only building within sight. A broken windmill leaned , screamed , whined, and moaned eerily as the wind gusted and the ancient fins would try to spin. An old man by the road glared at me. I hid in a scrub area behind the grave stones and camped numb with shock and worry. I was desperate with the fear that my feet wouldn’t make it to Westmoreland (population 485) the next day. It was 16 miles away and I couldn’t walk 16 feet! I slept fitfully, tormented by dive bombing insects and howling packs of coyotes. In my journal I wrote, “It would be such heaven not to be dominated by my pains.”

In the morning I fell into a brief deep sleep, just as dawn was breaking. I awoke at 8:00 a.m. I popped my blisters with a sterile needle (a new procedure for me), applied Mercurochrome and salve, stretched my sneakers, took two penicillin pills, band-aided my feet, slipped into my thinnest socks and with fear slipped on my jogging shoes. I stood up, thinking that if my blisters were not a factor, I’d be the happiest person alive. I was incredulous: my feet DID NOT HURT! Step by step, no pain. I was dazed. Was my mind playing tricks on me? There was no time to waste. I felt I had to hurry.

I studied my maps and decided to set off cross country along the old trail. I could actually see the faint swale of the trace which emerged from the scrub and headed off over the pastures and hills to the north west. I hit my high for the day, walked out of sight of roads or farms, I reveled in wild flowers, blue sky, birds, the softly rolling land stretching forever to the southern horizon, the hills to the north more pronounced. And then, I lost my nerve. I headed east to a sure road, went down from the prairie hills to the scrub valleys, and in the process of avoiding thickets, I became totally lost, disoriented, wandering in every direction. Finally I dug deep into my pack for the compass and forgot whether it was the red side or the white side of the needle that pointed north! I followed the sound of distant machinery noises and eventually ended up back in the old burial ground where I had started hours earlier! I reconsulted my maps and headed west only to find the bridge over the Vermillion River was out. The current was too swift and deep for a wet crossing. My maps broke the deadening news: there would be a 7 mile detour! I was dumbstruck! I had wasted previous feet and time wandering lost on the prairie and now a detour of 7 miles struck as the final blow. Was I losing my mind? There was no choice but to go on.

I changed into shorts and cool shirt which was to be the final fatal mistake, and left the old pioneer burial ground for the third time that day. My journal best describes that long important day. To make a long story short, blisters never once bothered me, but the arches and myriad muscles of my feet hurt with every single step. I cried a bit and paced off the miles one by one. Hours later , too late, I could feel my legs sunburning but knew that if I ever stopped to put on pants, I’d be unable to get going again. I walked a total of 19 miles. I had underestimated the distance to town by a mile which meant 20 extra interminable minutes of agony. I stepped through town in a blurr, went to the school with barely controlled hysteria and sat down in the home economics room.

Feeling like the biggest burden in the world, I was helpless to help myself. Somehow the fact that I had brought this condition upon myself by free choice, made being a charity case all the more uncomfortable. The young student teacher coped by ignoring me, but a young girl staying after school broke the silence with a few questions. Eventually I was led to the principals office under the premise, no doubt, that the buck stops there. Having stiffened alarmingly, my removal to that location was cause for comment around town for days. I proceeded up the hall inch by inch in a tight crouch.

Feeling like the biggest burden in the world, I was helpless to help myself. Somehow the fact that I had brought this condition upon myself by free choice, made being a charity case all the more uncomfortable. The young student teacher coped by ignoring me, but a young girl staying after school broke the silence with a few questions. Eventually I was led to the principals office under the premise, no doubt, that the buck stops there. Having stiffened alarmingly, my removal to that location was cause for comment around town for days. I proceeded up the hall inch by inch in a tight crouch.

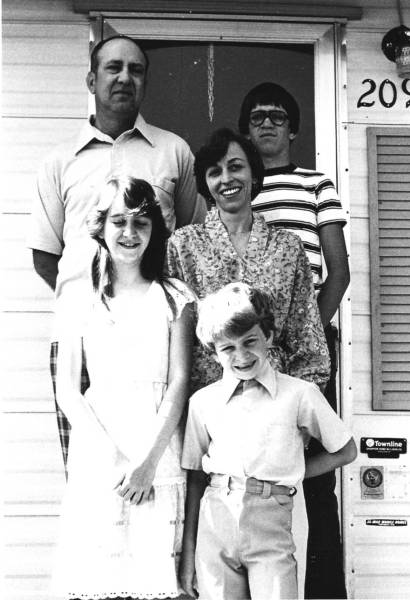

Mr. Wilkerson eyed me with mild irritation as the unwanted burden that I was. Finding no one to take me off this hands, he reluctantly carried my pack to his truck and took me to his home where his wife , Nola, and their children viewed me with equanimity while keeping a discreet mental and physical distance.

I lowered myself awkwardly to the floor just inside their front door. For about an hour I actually could not move my legs or neck muscles. It was the worst I’d ever been. To change position I had to lift my legs with my hands. Finally I was able to crab walk to the bathroom. It was becoming apparent that my sunburn would be the worst problem; ankles and legs were swelling grotesquely and the skin turning a dark blotchy purple.

That night I lay in the basement and did some hard thinking. I had not stopped to put on my pants because I would have been unable to move again so had allowed my legs to turn to a crisp. “There are real questions in my mind about my own competence and sense.” I confided to my journal. “There’s no excuse for allowing myself to get into such desperate physical condition. As a child I felt dominated by my body and at the mercy of my body-sickness, etc. As an adult, I decided to dominate my body with my head and so have said. ‘Body, you walk 20 miles’ and have forced my body to do what my head dreams up. The time has come to listen to my body and incorporate it into me and to respect it and listen to its signals and warnings. I must stop driving myself from town to town and start having confidence in camping and stopping. There has to be some big changes in my head, or I’ll never make it.”

By morning my leg muscles were better, but the severe sunburn made standing impossible, feet and legs swollen grotesquely. I wondered if they really would burst if I stood on them long. A nick with a paper edge brought forth a trickle of wetness from the tight edema.

By morning my leg muscles were better, but the severe sunburn made standing impossible, feet and legs swollen grotesquely. I wondered if they really would burst if I stood on them long. A nick with a paper edge brought forth a trickle of wetness from the tight edema.

I crawled about the house during the day and fixed lunch for 5 year old Terry. We were alone and I sat with Terry and ate what I estimated was a normal sized portion. After we ate I gobbled what Terry had left on his plate. But my mind kept wandering back to the leftovers I had put in the refrigerator. Unable to stand it, I crawled back to the refrigerator and sneakily wolfed down the luncheon leftovers. But my eye had spotted another dish of leftovers from the night before. Within twenty tortured minutes, there I was crawling furtively back to the kitchen with an anxious eye on the front door as I prepared to click open the refrigerator door for yet another raid. I stopped momentarily thinking, “Dear God! Have I sunk this low? Stealing food from the people who I had forced to take me in?” But down went the food with nary a blink. It was my first, but not my last experience with a run away appetite. And my eating binge hadn’t scratched its surface!

Later Nola returned home from school and recounted a conversation she’d had with a boy at school. The boy had warned, “I bet that when you get home that woman will have run off with half the stuff in your house!” Nola and I roared with laughter as there I sat unable to stand let alone “run off” and carry anything else on my pack! But still, my mind WAS lingering longingly over a box of crackers I had spotted on the shelf . . . .

May 13 still at Wilkerson’s I listened to my body which said, “not yet.” I think I have not been a bad thing to happen to this family despite my uninvited arrival and over long stay. Larry returned the money I had pressed on them. Maybe they’re concluding that I’m not really such a weirdo after all and am actually human. So far all of my intrusions on people have, I think, been mutually rewarding. In every case I arrive bizarre and leave human and well tolerated. People respond to my terrific needs and I respond with heartfelt appreciation (except when swiping food!). It’s a situation that quickly fosters mutual love and appreciation.

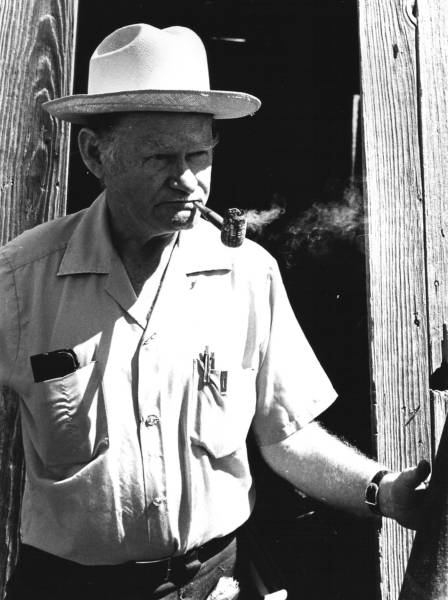

In the morning Nola took me to see “Doc” the local colorful character and editor of the town newspaper. “Doc” like the “Doc” on Gunsmoke television show, had wrinkling squinty eyes, wore an old cowboy hat and was surrounded with a wonderful aroma floating from his corncob pipe. Doc drove me back outside to a point out the Oregon Trail ruts that had escaped my pain blurred eyes days before. He pointed to the fields and I strained with my full concentration. “Now, do you see that hill coming down from the north?”

May 13 still at Wilkerson’s I listened to my body which said, “not yet.” I think I have not been a bad thing to happen to this family despite my uninvited arrival and over long stay. Larry returned the money I had pressed on them. Maybe they’re concluding that I’m not really such a weirdo after all and am actually human. So far all of my intrusions on people have, I think, been mutually rewarding. In every case I arrive bizarre and leave human and well tolerated. People respond to my terrific needs and I respond with heartfelt appreciation (except when swiping food!). It’s a situation that quickly fosters mutual love and appreciation.

In the morning Nola took me to see “Doc” the local colorful character and editor of the town newspaper. “Doc” like the “Doc” on Gunsmoke television show, had wrinkling squinty eyes, wore an old cowboy hat and was surrounded with a wonderful aroma floating from his corncob pipe. Doc drove me back outside to a point out the Oregon Trail ruts that had escaped my pain blurred eyes days before. He pointed to the fields and I strained with my full concentration. “Now, do you see that hill coming down from the north?”

“Yes!”

“Now do you see the big slashes coming down the side?”

“Yes, oh yes!”

“Well, that’s not the ruts.”

“Oh.”

“Those slashes are made by erosion, but the faint darker colored dips going at an angle are the real rail ruts. Do you see them?”

“Well, uh . . .yeah.”

Not wanting to be a veteran Oregon Trail walker who couldn’t even discern genuine ruts, I tried through sheer force of will to see the ruts, but my eyes were zipping frantically about without any real notion of where they were or what they looked like.

Not wanting to be a veteran Oregon Trail walker who couldn’t even discern genuine ruts, I tried through sheer force of will to see the ruts, but my eyes were zipping frantically about without any real notion of where they were or what they looked like.

Much later on a revisit to friends in Westmoreland I confessed that I never really knew which darker shaded areas were the ruts. My friend sheepishly confided, “Honestly Barbara, I’ve gone out there with Doc too and I’ll be darned if I can find them either!” We both finally laughed. It was a clear case of the Emperor and His New clothes!

Westmoreland’s pleasant green hollow traversed by a stream was a favorite camping spot for the wagon trains. I asked Doc for advice for my trip, and with a critical squinting eye on my purple bulging legs he said,

“You know, those pioneer women knew more than anybody does today about what to wear on the trail. They had those long long skirts that kept off the sun yet still allowed ventilation. But the most important thing you already know, “ he continued tactfully, “and that is making friends along the way.” I knew suddenly that he had spoken a truth. I would concentrate less on hiding and more on making friends. My mental set was changing importantly from one of defensiveness to one of assertive good will. Before leaving Doc asked if he could snap a picture for the paper. It had begun to rain. As I hesitate to stand in the downpour, Doc cracked, “You were wet before you were dry, girl.” And grinning broadly through the deluge, I acquiesced.

“You know, those pioneer women knew more than anybody does today about what to wear on the trail. They had those long long skirts that kept off the sun yet still allowed ventilation. But the most important thing you already know, “ he continued tactfully, “and that is making friends along the way.” I knew suddenly that he had spoken a truth. I would concentrate less on hiding and more on making friends. My mental set was changing importantly from one of defensiveness to one of assertive good will. Before leaving Doc asked if he could snap a picture for the paper. It had begun to rain. As I hesitate to stand in the downpour, Doc cracked, “You were wet before you were dry, girl.” And grinning broadly through the deluge, I acquiesced.

I was grateful for shelter that day. There were continual weather warnings on TV. The hail and windstorm became very powerful, frightened. The large white hailstones looked like popcorn popping all over the ground.

My enforced physical recovery gave time for some more needed mental centering. I wrote in my journal: Have been thinking of the mind-body business again. There’s no doubt that I have been able to trance-like separate my consciousness from body torture and physical surroundings. I then plod on a rhythm for an hour oblivious to everything but the random thoughts in my head. If someone interrupts with a ride offer, I’m amazed at how far away I was as I snap back to the present. In view of my body’s revolt later, sunburn, blisters, etc., I think maybe this method is not good except in emergencies. My sunburned leg has been cooked about two inches deep. The pain is from the inside. I feel so very apologetic to my body for abusing it as a tool for my cerebral plans.

Thinking more of the altered mental states while walking, I can have 2 or 3 definite mental activities, 1) my thoughts, 2) a definite yet not fully conscious singing of some song which spills through to consciousness only after quite a few verses and 3) subliminal awareness of where I’m putting my feet. The singing part is interesting. For a few miles before St. Mary’s, I was singing “ The Bells of St. Mary’s before I realized the song or what triggered it.

On my last day with the Wilkersons, Nola put aside her numb housewife demeanor and talked movingly of her grandmother who immigrated from Germany at age 4 to western Kansas and remembered her father plowing (cutting) a furrow in the sod and the kids picking up the cut pieces and bringing them to make the sod house. Her grandmother remembered huddling on the deep window sills set in the sod houses when it rained. It was the driest spot. She also was scared with the memories of snakes which often sought the sod house for their own. Nola talked of the windmills and pumps and her father “following the harvest”. She talked of her own emergence as a person after trying to be the perfect wife was not satisfying. Kansas or Boston, women follow similar patterns as we struggle to find and identity outside of unfulfilling prescribed roles. That evening there was a warm feeling in the house. We were all happy to have found each other.

On my last day with the Wilkersons, Nola put aside her numb housewife demeanor and talked movingly of her grandmother who immigrated from Germany at age 4 to western Kansas and remembered her father plowing (cutting) a furrow in the sod and the kids picking up the cut pieces and bringing them to make the sod house. Her grandmother remembered huddling on the deep window sills set in the sod houses when it rained. It was the driest spot. She also was scared with the memories of snakes which often sought the sod house for their own. Nola talked of the windmills and pumps and her father “following the harvest”. She talked of her own emergence as a person after trying to be the perfect wife was not satisfying. Kansas or Boston, women follow similar patterns as we struggle to find and identity outside of unfulfilling prescribed roles. That evening there was a warm feeling in the house. We were all happy to have found each other.

Sunday, May 14, Mother’s Day the Wilkersons wer more relaxed and happy than ever, solicitous of me, sending me off without my pack with promises to drive it to me later which they did. They brought cookies and well wishes and warm sincere pleadings to call collect if I ever needed help. As they left for the last time, Nola said, “We miss you already and since you were here, we’re seeing the countryside with whole new eyes.” I blinked back a few tears and sighed as their car dipped out of sight. Why is it that everything seems to work out for the best? This interlude has been shot rejuvenation, new body, new attitude. My mileage per day has been shot so there’s nothing to do but calm down and go on. It was a sentimental Mother’s Day as I thought of my own children and headed the last 2 ½ miles to Blaine.

From Westmoreland to Blaine I followed the road like a giant lazy roller coaster. Each crest gave glimpses like the huge swells and rollers of the ocean. The pioneers thought so and said so too. The land is high and dry. At one crest I stopped and looked back and suddenly realized that I was leaving behind the Kansas River Valley forever. It was an uncanny awareness. That swell appeared no different from the rest, but it was the last possible glimpse of that land. I had labored 155 miles through it, the southern low hills, the fertile flat bottoms, and up and across the northern edge of the hills. The term valley is valley Kansas style. It appears to be incredibly subtle, hills 25 miles away and only a few dozen feet high, a vast flat land and more tiny hills, the Kaw River there somewhere, but invisibly tiny. Nevertheless, this barely perceptible valley was as vivid to me as Yosemite, and I’m sure I was tuning into pioneer awareness and emotion as I went over the crest of the hill and said “goodbye”. Looking forward was thrilling. I felt the divide marked great progress. The day was a miracle, the breeze cooling, the pack riding effortlessly (for a change), my feet painless. A few more rollers and I gazed far far ahead, toward Nebraska. It was like sensing the curvature of the earth by the ocean shore.

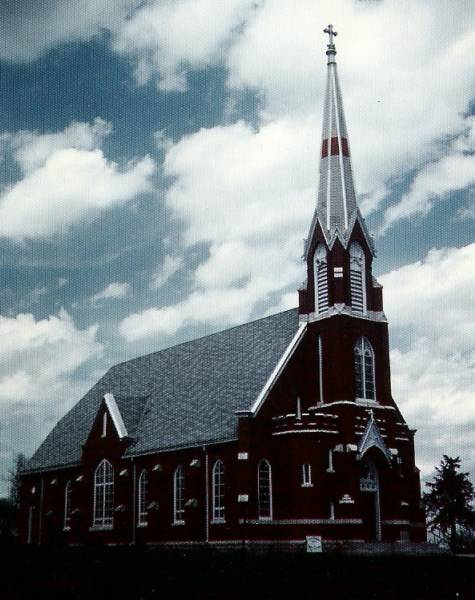

Then upon a modest crest to the left appeared, the tips of a small army of cement crosses like the topsy turvy helmets of crusaders. What in the world were they? As I gained on the hill I discovered the crosses were the tips of tall Catholic Cemetery markets, plunked down there on the plains. Another scarcely believable sight arrested my attention; about 2 miles north on the crest of a long roller, gleamed red, strong red in the sun, rode a gothic spired church, a three story chunky brick schoolhouse and a fat square rectory. The blue sky formed a backdrop and the green-tan prairie the foreground setting. Surely I was about to witness a grand ethereal pageant! Closer inspection revealed a very few tiny white houses nestled in a trough by, Blaine! But there were just a scant few houses with the empty prairie surrounding the tiny town as far as the eye could see. How or where did the people come from to fill the school and the cathedral?

From Westmoreland to Blaine I followed the road like a giant lazy roller coaster. Each crest gave glimpses like the huge swells and rollers of the ocean. The pioneers thought so and said so too. The land is high and dry. At one crest I stopped and looked back and suddenly realized that I was leaving behind the Kansas River Valley forever. It was an uncanny awareness. That swell appeared no different from the rest, but it was the last possible glimpse of that land. I had labored 155 miles through it, the southern low hills, the fertile flat bottoms, and up and across the northern edge of the hills. The term valley is valley Kansas style. It appears to be incredibly subtle, hills 25 miles away and only a few dozen feet high, a vast flat land and more tiny hills, the Kaw River there somewhere, but invisibly tiny. Nevertheless, this barely perceptible valley was as vivid to me as Yosemite, and I’m sure I was tuning into pioneer awareness and emotion as I went over the crest of the hill and said “goodbye”. Looking forward was thrilling. I felt the divide marked great progress. The day was a miracle, the breeze cooling, the pack riding effortlessly (for a change), my feet painless. A few more rollers and I gazed far far ahead, toward Nebraska. It was like sensing the curvature of the earth by the ocean shore.

Then upon a modest crest to the left appeared, the tips of a small army of cement crosses like the topsy turvy helmets of crusaders. What in the world were they? As I gained on the hill I discovered the crosses were the tips of tall Catholic Cemetery markets, plunked down there on the plains. Another scarcely believable sight arrested my attention; about 2 miles north on the crest of a long roller, gleamed red, strong red in the sun, rode a gothic spired church, a three story chunky brick schoolhouse and a fat square rectory. The blue sky formed a backdrop and the green-tan prairie the foreground setting. Surely I was about to witness a grand ethereal pageant! Closer inspection revealed a very few tiny white houses nestled in a trough by, Blaine! But there were just a scant few houses with the empty prairie surrounding the tiny town as far as the eye could see. How or where did the people come from to fill the school and the cathedral?

A born and bred easterner finds it mindboggling to discover dirt roads stretching dozens and dozens of arrow straight miles intersected at right angles rigidly every mile with identical dirt crossroads in a colossal gridwork pattern. But to top this off with a cathedral on the windswept prairie is inconceivable, but there it sits.

Later when I went into the church, I gasped. It was as elaborate and ornate with vaulted ceilings and gold statuary as any big city church. The stained glass window, robed figures and Biblical scenes were as glorious as any I’ve ever seen. Astonished, I was told that there are two other similar cathedrals within 10 miles, each representing the three tiny original ethnic settlements: Blaine was Irish Catholic, Wheaton Dutch Catholic and Fluch German Catholic.

Scarcely believing my eyes I walked past the bastion school (1928) and church and approached a Chicano girl raking leaves. The Hernandez family, 4 teenage sisters and their mother, Benita, my age, incorporated me into the family with total grace and naturalness. This Mexican family fed me a most sumptuous meal. The serving bowl of mashed potatoes drew me magnetically. Should I take lots of small helpings or a few tremendous ones? I couldn’t stop. My body drove me despite my embarrassment and anxiety about my great cravings. As the meal wore on I consumed ½ gallon of iced tea and the whole serving dish of mashed potatoes and gravy. First I craved the salty gravy and potatoes, then the sweet tea, then the potatoes and gravy, then the tea. I stared finally at the empty bowl and pitcher. I had eaten an enormous quantity of food and I felt guilty about my gluttonous appetite, but my hunger had won and I had eaten ravenously.

Benita gave me a tour of her home, formerly the nun’s quarters for the cathedral and school next door. The sturdy old house was large with carved newel posts, stained glass, round windows in the entry and foyer. Years of neglect had cracked the plaster and darkened the carved woodwork, but when Benita told me she had bought it last year at an auction for $650, I knew I was in never never land!

For the next 4 hours I lay on the library floor and listened to Benita’s lilting Spanish accent as she led me through a roots type of narrative of her ancesters’ migrations and struggles. It was a dreamlike recital as her cultural heritage met and diverged and remet my WASP (White Anglo Saxon Protestant) background. Although the temperature was warm (throughout) I shivered and felt very cold – sunburn? Sickness?

Benita grew up in a family of 12 children. She raised the old way, strict, no smoking, drinking, hanging around town. She was always required to dress properly.

Benita’s winding recital hypnotized me as she led to entranced across the years. Her grandfather worked, slaved, in the mines. Her father farmed the land, a little patch down by the Mexican Texas border, clearing it acre by acre. Eventually the land was stolen from him in a shameful land swindle, but she has always yearned to buy it back since “his sweat and blood was in it”. Her father, a proud and independent soul, was a rebel toward the Catholic Church. He pronounced the priests were corrupt and took too much from the peasants. Our dreamy reverie of the misty past was interrupted by a sharp knock on the door and in strode “Pearl the girl”.

Pearl, a rawboned and large woman had the presence of a giant, the appearance of a 40 year old and the vitality of an adolescent. She was 60! She bowled me over with her thundering personality. Benita, Pearl and I talked far into the night, a coven of witches in a secret society. Missing Text rather than grown, all the old features are intact, and it was as if the old days and the present moments were the same. The old nun’s quarters absorbed it patiently. Pearl said, “Since we’ll never meet again, this is a good time to tell secrets, “so with a devilish gleam she told me how 20 years ago when she was in her 40’s, she . . . .

“My cup runneth over,” said Pearl before she left. It expressed my feelings about the evening with these wonderful people.

I awoke to another glorious day and was on my way by 8 am. “My cup runneth over. My cup runneth over.” That benediction from Pearl and night before overflowed from somewhere inside me and I found myself chanting it rhythmically as I walked. After a few miles I again perceived a basic landscape change. The Oregon Trail had followed the Kaw River Valley, had hauled up to the huge dry lands, keeping as usual to the high ridges and now I could see in the soft distance, was headed toward another almost imperceptible but more heavily treed depression, the Valley of the Little Blue River which I would follow deep into Nebraska.

I turned into a very crude gravel road which was to take me many miles past abandoned farms. At the turn a hoky farm sprawled in disarray. Unlike a good or bad housekeeper, the farmers mess or tidiness sits outside for all the world to see. A man and woman eyed me suspiciously, hands shading eyes. I called out assertively, “Good morning! I’m walking the Oregon Trail.” The change was dramatic. There was an immediate relaxation and sigh of relief, and they repeated and called to each other, “She’s walking the Oregon Trail. She’s walking the Oregon Trail,” in a vivid hillbilly trang of amazement.

I pushed on in a state of peace and grace, at one point even forcing deep into the stupor of pain and heat once again as I sat on the steps of an 1881 one room school house to change my shoes in a futile attempt to make things nice like they had been earlier.

Finally, hours later, the rarely used road dipped from the sweltering fields into a cool hollow. I passed an ancient stone hog barn, saw a windmill sticking up and the jumble of sheds and small barns. Then the small very very old house showed through the trees. A colorful profuse flower bed nestled around the house in the tight little hollow, and I thought hopefully, “People who like flowers this much must be good people.” I could feel my sunburned face throbbing; my back and pack were soaked with sweat. I opened the ancient gate, “the Smith’s” it said, and I crossed the tiny stepping stoneyard, passed a water pump and lots of kittens and knocked on the door. The reassuring grin of an old healthy farmer greeted me. “My cup runneth over.” Now almost a year later, I can still feel the nervous, anxious anticipation and the flood of grateful relief when that unforgettable smiling face appeared.

Clarence and Lillian Smith have farmed this tiny shady farm in the hollow since 1931. They are both 77 and look and act 60. Clarence is topped with an up swinging overgrown brush cut, of all things! When they first came, half a century ago, they routinely found Indian arrowheads, and artifacts by their creek, but not knowing its value, covered it to expand the fields. The farm was built by homesteaders who worked it till 1931 when the Smith’s bought it. It is a vivid contrast to most western farms in that it’s cozy and tightly treed in its protective hollow. That’s probably why the Indians and first homesteaders chose that spot. The chicken yard provides an incessant cackling background hum. Lillian showed me the old historic stone barn, stone hen house, two half stone red similar to a root cellar, entered by cellar type doors. Inside are shelves lined with canned goods from the vegetable garden, crocks, etc. Sometimes the crocks are built into the floor for sauerkraut.

Occasionally on my journey a person would make a simple gesture or statement that would be such an appropriate expression of support or approval for me that indeed it seemed made in heaven. Lillian never did so much talking, but soon after I arrived hot and hone weary and footsore, she eyed my sweat soaked pack with curiosity. Then is an endearing gesture she accepted my suggestion to try it on. Clarence and I hoisted the wet sweaty 38 pound monster onto her 77 year old petite back and she teetered about the tiny living room exclaiming, “Ohhhhh, it feels like it’s pulling me backwards.” In her own way she said she was impressed that I was carrying such a heavy thing and thereby endeared herself to me forever.

Clarence and Lillian Smith have farmed this tiny shady farm in the hollow since 1931. They are both 77 and look and act 60. Clarence is topped with an up swinging overgrown brush cut, of all things! When they first came, half a century ago, they routinely found Indian arrowheads, and artifacts by their creek, but not knowing its value, covered it to expand the fields. The farm was built by homesteaders who worked it till 1931 when the Smith’s bought it. It is a vivid contrast to most western farms in that it’s cozy and tightly treed in its protective hollow. That’s probably why the Indians and first homesteaders chose that spot. The chicken yard provides an incessant cackling background hum. Lillian showed me the old historic stone barn, stone hen house, two half stone red similar to a root cellar, entered by cellar type doors. Inside are shelves lined with canned goods from the vegetable garden, crocks, etc. Sometimes the crocks are built into the floor for sauerkraut.

Occasionally on my journey a person would make a simple gesture or statement that would be such an appropriate expression of support or approval for me that indeed it seemed made in heaven. Lillian never did so much talking, but soon after I arrived hot and hone weary and footsore, she eyed my sweat soaked pack with curiosity. Then is an endearing gesture she accepted my suggestion to try it on. Clarence and I hoisted the wet sweaty 38 pound monster onto her 77 year old petite back and she teetered about the tiny living room exclaiming, “Ohhhhh, it feels like it’s pulling me backwards.” In her own way she said she was impressed that I was carrying such a heavy thing and thereby endeared herself to me forever.

There was a poignant shadow hanging over the Smiths. Their little farm so pulsating with sentimentality was to be sold that fall. They were living their last spring, their last summer, their last months and weeks and days there. After half a century of plowing and gathering fresh eggs and weeding the flowerbeds, the Smiths were leaving, moving into town. Clarence said that sometimes this made him feel so sad that his heart hurt, “but”, he said bravely, “there comes a time when you just have to let go.” Somehow I felt that the old farm would hate to let go of them too. The Smiths gently and unknowingly forced me to make a big policy decision about my trip. The Benton farm, a commune, was nearby. The Smiths had a very special relationship with these people and wanted to take me there for a visit. Spending an extra day would set me another day behind the Donner Party timetable, yet surely it would be foolish to wear tight blinders in pursuit of my Donner goal. The trip had a way of unfolding to the commune with the Smiths. This flexibility became a part of my philosophy and was to serve me well in the future. Through it, however, my ultimate goal never wavered, as the man on the bus to St. Louis had suggested.

Thomas Hart Benton, the famous painter and friend of President Harry Truman (who called him” the best damn painter in America”) started a commune near the Smiths. Previous to the Kansas purchase, the commune had two branches, one in Boston and one in Los Angeles. I was told that when a farming branch was needed the planners drew a line between Boston and Los Angeles, circled an area halfway between and bought land within that area. Communes (throughout the country and especially to conservative mid-plains people) connote images of drugged hippies, free love and bare breasted women behind plow. I assumed these images to be incorrect yet, and yet, well, I was curious. There was something about the way old Clarence lauded and defended his commune friends that impressed me. There was courage and independence in the way he stood up for them. I wondered if he had endured criticism from the local Kansas folk for his association. “Their just grand fine people”, Clarence earnestly declared of the commune community, “why, whenever I need some help here on the farm, they just come right over and never ask for a cent, and that’s the way it works when they need a hand or advice from me. Aw heck, they’re just the nicest people, I just can’t find anything bad to say about them. Now they do have babies there, there’s no doubt about that, and I don’t know that any are married, but where and how those babies come from, well, I just figure that’s their business. I’ll tell you one thing, I just can’t get over how nice those people are, why I have no complaints at all.”

Clarence drove the long mud rutted road to the Benton Farm, someday hopefully big enough to be named Bentonville. He pointed to some high UNREADABLE TEXT UNREADABLE TEXT – UNREADABLE TEXT I expected to see.

We pulled up to a collection of buildings set among some rare Kansas hills. Not only was there no beehive of activity, there was no one around. I took a minute to give my eye a critical inspection tour. There were neat fields of crops, a few barnyard animals grazing here and there, a couple of saggy barns, a nice enough old house and a new structure, a large building constructed high and against a hill. Finally a tall lanky guy unwound himself awkwardly from some farm machinery he was repairing and shyly suggested we try an old house to find someone.

In the old house we found a young woman squeezing bags of dripping stuff making cheese. She said that she had tried something new with it and that the cheese was good. She didn’t have to tell me; I could smell it and felt nearly frantic wanting some. Instead, she offered us coffee. A few more adults wandered in and we all sat around the table. We could have been any collection of ordinary people anywhere. The commune people drank coffee by the gallon and smoked like chimneys. So much for the health image!

Another man came into the kitchen and lounged next to the stove where the coffee was brewing. Divora, the woman sitting next to me stood up and went through considerable inconvenient climbing over people and chairs to fetch and serve him the coffee he stood six inches from. So much for the image of new roles for women!

I was interested to hear that they want to considerable inconvenience to avoid sending their children to the public schools. “Aahaaaa,” I thought, “here comes the wild free school scene!” But in fact they were about as old fashioned and strict as possible, copy books, drilling, UNREADABLE TEXT UNREADABLE TEXT UNREADABLE TEXT So much for the free school scene!

Divora graciously took time for her million chores to give a tour of the farm. At the moment there were 13 adults and 15 children living there. The number of adults is variable since they travel freely between the three sections across the country. Their goal is to be self-sufficient eventually, with the farm and major food supplier for the three. As I listened to their worthy and ambitious goals and looked around the tiny conclave, I paled at the thought of the work ahead and silently rooted for them as one would for a favorite team way behind in a lopsided score. The current crisis was the broken farm machine, but it wouldn’t be long before the sagging barn would threaten collapse and the approach road impassable through the swamp and . . . . and. . . .. So much work and so few people! But the big house on the hill was their pride and joy as indeed it merited. They have cut and cured and stained their own lumber from their own land. They have hand carved their own banisters and drawn and designed their own plans. Antique furniture from Europe proportedly used by the Three Musketeers, tables and ancient chairs, reposed in settings worthy of their importance. The house was creative and impressive.

After two hours of imposition on these people struggling against heavy odds to do so much work, we turned to leave. I wished I could have talked with Divora longer but my real questions were too impertinent for a mere two hour acquaintance. With our thoughts on history, Divora showed me an old child’s school slate with a little girl’s name scratched on it which had been turned over unexpectedly by a plow in the field. Thoughtfully, she said.”Did you ever think that you might be one of the Donner Party reincarnated?”

“Not really,” I said. Such a thought seemed too presumptuous.

Later as I prepared to leave, Mr. Smith gave me a buckeye to carry for health and luck. I carry it still. I waved goodbye as the old road dipped down past the enormous elm tree.

Late in the day I passed the townsite of Bigelow. No buildings remain in the area where the town once flourished. Virtually every speck of evidence was removed in case of flooding, by the detest Army Corps of Engineers to build a “damn dam” downstream. Along the road, however, bloom patches of Day Lilies and Iris planted by an old woman, Mary Carpenter, fifty years ago. She planted flowers on her daily walk to the post office. It’s all that remains of Bigelow.

In parts of Kansas there are miles and miles of stone fence posts. I .am told they are limestone. When first removed from the earth and cut, they are soft. After years of air and weather exposure, they become very hard.

After walking an hour, an old wisened farmer drove up and stopped his pickup truck. He smelled of alcohol, red shiny face, and my prejudices flared up. I got ready to smash him with my water bottle if necessary. He asked me the usual questions and seemed impressed. He contributed a few trail rut stories and blearily studied the map. Later (hour) he drove up again and pulled in front of me, blocking my way. Again I got ready to smash him, but I was in for a surprise. He had gone home and his wife had baked some cookies which he then gave me in a brown paper bag with a big bottle of Pepsi Cola. I was humbled.

Walked 12 miles in 4 hours. Right in the middle I was overcome and overwhelmed unexplicably with a desperate longing for my family. Did Paula need me? Until I was nearly frantic with the conviction that they wanted me to call. Marysville was too far away and I started to cry. Now here’s a secret. When I’m out in nowhere without a house visible for miles, I indulge in unrepressed, uninhibited crying. I make face like little crying kids. I make noises like little kids, and then I make up my own most (to me) heart rendering wails, like a little kid getting a shot, etc . Then I decide to send my peace vibes to the family telepathetically, and I felt better. I can only guess the whole thing was a hormone swing. But I remained shaky for the rest of the night.

Before approaching farms to inquire about camping on their property, I go through my quick routine to make me look harmless and friendly; off with the sunglasses and bonnet, neaten my hair, straighten my bowed back, relax and brighten my face. I do have a cynical streak.

After I introduce myself, name, where I’m from, what I’m doing, etc., I say “My husband and kids are joining me on the trail as soon as school’s our.” That’s always the softener. “ahhh. . . She’s a MOTHER . . . . .and her family is going to WALK together!” pause . . . .”Would it be OK with you if I unrolled my sleeping bag somewhere on your property for the night?” smile. . .

Once I was dumbstruck. “No, I think not. I don’t know you and I don’t trust you.” I was a woman alone, at night, in the middle of nowhere, crippled with sore feet, exhausted. Me? Dangerous? After a tear quivered threateningly on my eyelash, they relented. I hobbled to the yard and dropped and kept wiping the now flooding tears with my sweaty sleeves. I must have looked as forlorn as I felt because the people were nice to me after that with offers for shelter for sleep.

One morning a farm family invited me in for a chat. On the table was half a grapefruit, uneaten and unoffered. Later on the road I was mad at myself for not asking for the grapefruit. Mile after mile I was obsessed with mouthwatering thoughts of that damned grapefruit.

One morning a farm family invited me in for a chat. On the table was half a grapefruit, uneaten and unoffered. Later on the road I was mad at myself for not asking for the grapefruit. Mile after mile I was obsessed with mouthwatering thoughts of that damned grapefruit.

I was approaching an important landmark on the Donner Trail. I put aside my 20th century preoccupations for a while and pondered the 1846 scene. Prominent among the Donner Party was the Reed family. James Reed, the father, was a dynamic and impetuous co-leader of the wagon train. His wealth and arrogant manner often separated him from the rest of the party who in the frontier code of the day respected wealth but resented its conspicuous display. His wife, Margaret, a frail 32 year old woman, had born four children, and we are told, suffered from migraine and various other complaints. Traveling with James, Margaret and the four children, was Sarah Keyes, Margaret’s mother. Having raised her own family, Sarah was well on in years and failing, but stubbornly refused to be separated from Margaret, her beloved and only daughter. One blinks and rereads this passage. An old woman near the end of her years leaves behind grown sons and a comfortable life to follow her married daughter into the wilderness. Sarah’s devotion was firm, so firm that James Reed had a special wagon built, oversized and with a springy feather bed just to ease the journey for his mother-in-law. It is a story with a Victorian sentiment oddly startling to 20th century senses accustomed to 20th century love stories.

During the last week in May 1846, barely as the journey had begun, Sarah Keyes died. Her granddaughter clipped a lock of her hair which she would carry through to California. Sarah was buried in an achingly beautiful little valley that was named Alcove Spring. Here a small streamlet spills over a rock ledge into ferny glen and the grass grows green and lush in the natural meadow. James F. Reed carved his name and the date on a boulder that formed the natural enclave.

Late in May 1978, I climbed over the fence through ber cans and walked back to the half forgotten little spring. The stream bed is a jungle of tossed boulders. My eye wandered across the lumpy landscape as I began to climb across. Without any strain or search, I looked down and there it was: J.F. R(eed) worn away, 26 may 1846. I sat next to ti resting my hand on the bumpy surface for a while, and then I got up and limped on.

The day I stopped at Alcove Springs was also a big day for dogs. Throughout the journey I was to be an object of thundering excitement for thousands of dogs patrolling thousands of farmhouses. Time and again they would spot me coming and either wait lazily until I came abreast of their property, or zealously rush for the confrontation on first sight. In either case we came to immediate agreement: I would not alter my route or pace one iota and they were free to put on an impressive pyrotecynec show of noisy defense. I perceived a sense of mutual amusement in that arrangement.

But on the day of Alcove Spring. I found myself out of water in addition to the other familiar complaints of fatigue, overheating and mind dulling foot pain. I turned into the circular drive of an old house with intention of asking for a refill of my water bottle. Half way to the front door the peaceful scene electrically erupted into a bedlam of a dozen (or more) snarling, snapping, growling, barking dogs, all sizes but of similar rotten dispositions. They leaped from under the shrubbery and dashed out from under the cars. Crossing in front of their house would have been provocative enough but to actually walk ON their territory! This surely was a declaration of war to them. Such audacity! Unforgiveable.

During those hours fo the day when my physical agony weighed heavily with every step, my spirit and will followed unusual priorities. In this case even mad dogs were not enough to induce me to take one extra or unnecessary torturous step backward. My goal was to get some water from this house. To turn back then would have made the painful 30 foot trudge in vain. So I continued on through the astonished dogs up to the porch and knocked. It didn’t occur to me until later that the woman’s shocked expression on seeing me was the realization that her dog defenses had been pierced, but she gave me the water and I continued around and out the circular drive with the dog’s snarling in impotent fury. I’ll never know why those dogs didn’t bite. I think that my abnormal attitude of determination and preoccupation with other things beyond fear threw them off. Later I looked back on that interlude in amazement! “Fools rush in where angels fear to tread”. Maybe naivety does have advantages now and then!

I checked into an old Gunsmoke TV show type hotel, old men sitting in the paneled lobby, ancient elevator, cracked Spartan plaster rooms. The little booth-filled restaurant downstairs serves luscious food, cheap and lots and wonderful 24 hours a day. My room is $7 per night. I’m on the third floor and, surprise! Right over the railroad tracks, DING DING DONG whoooooo whooooo and the windows rattle mightily and the bed shakes punctually every 30 minutes! The hot water tub faucet is so mineral encrusted that the water comes out as if through a hypodermic needle. It took 20 minutes of fierce running before it got hot and 45 minutes to fill the tub. I love it!!! ( A year later this venerable old hotel had closed. I peered through the windows into a sad and empty lobby, the marble floors already deep layers of aging dust, so sad.)

I checked into an old Gunsmoke TV show type hotel, old men sitting in the paneled lobby, ancient elevator, cracked Spartan plaster rooms. The little booth-filled restaurant downstairs serves luscious food, cheap and lots and wonderful 24 hours a day. My room is $7 per night. I’m on the third floor and, surprise! Right over the railroad tracks, DING DING DONG whoooooo whooooo and the windows rattle mightily and the bed shakes punctually every 30 minutes! The hot water tub faucet is so mineral encrusted that the water comes out as if through a hypodermic needle. It took 20 minutes of fierce running before it got hot and 45 minutes to fill the tub. I love it!!! ( A year later this venerable old hotel had closed. I peered through the windows into a sad and empty lobby, the marble floors already deep layers of aging dust, so sad.)

My interactions with people are very emotional and draining and staying alone in this hotel is very much needed. It restores and rejuvenates me. Today walked 14 ½ miles, 2 new blisters, toe and heel.

The term limp connotes an image of walking out of balance to favor rain with every step, then the whole gait becomes peculiar. To keep the pack from bouncing, to land as softly as possible on the heel, to avoid bending the feet too far, to place the foot on whatever angle of surface would take pressure off the sorest parts, to keep the stride short enough to minimize pain but long enough to keep moving to put full weight on each foot as short a time as possible; these were the delicate factors to be gauged and adjusted with exquisite precision. The tension of walking on egg shells or thin ice must be similar. Each hour of walking in a day accelerated this accumulation of tensions until my whole being felt embattled and a touch of dementia would set in.

The term limp connotes an image of walking out of balance to favor rain with every step, then the whole gait becomes peculiar. To keep the pack from bouncing, to land as softly as possible on the heel, to avoid bending the feet too far, to place the foot on whatever angle of surface would take pressure off the sorest parts, to keep the stride short enough to minimize pain but long enough to keep moving to put full weight on each foot as short a time as possible; these were the delicate factors to be gauged and adjusted with exquisite precision. The tension of walking on egg shells or thin ice must be similar. Each hour of walking in a day accelerated this accumulation of tensions until my whole being felt embattled and a touch of dementia would set in.

Small and large instances of kindness from perfect strangers again and again would bring me back to rationality. The unexpected gentle concern of farmers, “Whaddar ya doin?. . . I sure do admire ya for it. Madam.” “Thad house up thar is empty and yer sure welcome to it if ya need a place to spend the night.” “I sure would be happy to drive you up the road a piece but I understand your decision to walk it all the way.” In one section the farmers plowing for miles and miles somehow passed word along about what I was doing and my pitiful looking condition. Each would come to the edge of the field to offer water and encouragement and concern as I passed his section. Once a tractor pulled up on the road behind me. I was too pained and stiff to turn to look, but the soft and gentle way he decelerated and stopped said as much as his kind words.

One man passed me not saying a word but beamed the most radiant smile I have ever seen. I turned into the lane leading to the loveliest farmhouse and barns and flowerbeds and vegetable gardens and lawns imaginable. It reminded me of the Country Morning cereal boxes. It was owned by a German family, the Heistermans, who kept things in a state of perfect German tidiness.

Mr. Heisterman was the man who had beamed the silent smile. He hadn’t spoken verbally because a laryenjectomy had taken his voice box. But I learned something about communicating in that house. Perhaps because he couldn’t talk, he was vividly expressive with his eyes and manner, radiant with emotion and eagerness and encouragement, bursting with things unsaid. Occasionally he used a pencil and pad on which he wrote with great care and neatness, no quick scribbling for him!!

Mr. Heisterman had a lifetime of interest in the Oregon Trail which traversed his crop fields. Since he was unable to communicate freely, the situation was poignant but bridged somewhat, I think, by our mutual appreciation. He disappeared and reappeared with his arrowhead collection carefully mounted and framed, at least 50 perfect various sized arrowheads, all found on property he’d farmed. He had spent many hours searching plowed fields after rains. He also showed me a pony shoe, a mule shoe and an oxen shoe he’d found on the Oregon Trail across his land.

That night I slept on their land. Mrs. Heisterman the night before had viewed me with some suspicion and distrust that I had not fully dispelled. In the morning Mrs. Heisterman said that she knew I wasn’t bad because she’d been able to sleep during the night, and if I’d been a bad person, she wouldn’t have been able to sleep. It was her acid test and , whew! I passed it!

As I was packing to leave I heard a shy knock and in came Mr. Heisterman who sweetly presented me with a little 4 leaf clover for luck. He disappeared and after a while came back with two more, real thank you good luck offerings. I placed them deep in my map pile by Utah and California for a surprise when I got that far. It didn’t seem possible then, Mrs. Heisterman and I had also become friends at last and I left with unexpected emotion.

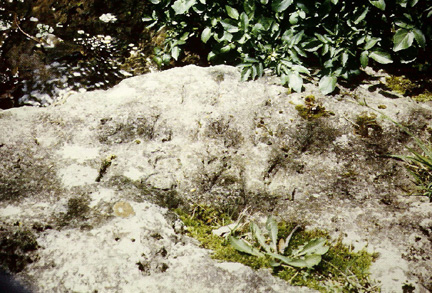

One year later Mr. Heisterman emerged carrying a flat stone orivinally turned up by his plow 14 years ago and since having served as a filter cover for his water pump. A few months after my visit he had walked past the innocent looking stone just as he had a thousand times before, but he stopped and looked again. The angle of the sun had thrown into shadowed relief what appeared to be faint lettering. The year 1842 was visible and after hours of searching the weathered slab, the words Rest in Peace appeared. A tantalizing puzzle, the pioneer grave marker yields its secrets slowly. The letters Edna and 18__ have been deciphered, traced as the tenuous connection of human beings therein to bridge the gap of over 100 years. Mr. Heisterman has a new pump cover, though surely not as exotic as the first!

A few hours later I suddenly realized I was on my last Kansas mile. In a burst of emotion I turned and looked back. Goodbye, Kansas! I wept tears of thankfulness that I had reached the border and that I head left behind a successful struggle, thereby part of me.

... the road like a

giant lazy rollercoaster

Emil and Lula Heisterman, REST IN PEACE could still be read along the left side.

Alcove spring,

J.F.R (eed), 26 May, 1846.

J.F.R (eed), 26 May, 1846.

Along the trail in

Kansas

The Lewis farm was every inch a romantic idyll (1979)

The Lewis' old fashioned kitchen looked like a movie set

The Wilkersons: Larry, Barry, Sherry, Nola and Terry (1979)

"Doc" 1979

... about 2 miles north on the crest of a long roller, gleaming strong red in the sun rode a gothic spired church

I passed an ancient stone hog barn. A colorful profuse flowerbed nestled around the little house and I thought hopefully, "People who like flowers this much must be good people.

I passed a red pump and knocked on the door.

Benton commune kitchen

Fifty years ago Mary Carpenter planted flowers on her daily walk to the post office. Those flowers are all that remains of the little village of Bigelow.